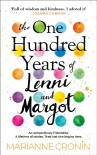

The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot by Marianne Cronin (e reader books txt) 📗

- Author: Marianne Cronin

Book online «The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot by Marianne Cronin (e reader books txt) 📗». Author Marianne Cronin

‘Stop pretending it’s him that you want!’

As more of the crowd, impatient to get to Grosvenor Square and see the letter delivered, pushed forwards, it was as though we were standing in the middle of the sea against a strong current that was pulling us all in great waves. But she didn’t move and neither did I.

I reached out and took her hand.

The noisy couple who lived in the bedsit below us clattered down the street under the light of the lamp posts. He was only wearing one shoe, but she had both her high heels on and they clacked along the path as they ran, hand in hand.

When they got to the bottom of the stairs, they saw me but said nothing. They picked their way carefully up the steps, but her ankle gave way and she stumbled, falling into my suitcases, which rattled down the steps. The smaller case sprang open, vomiting everything inside it onto the pavement. ‘Oops!’ she said, and as they let themselves inside and shut the front door, I heard them both laugh.

Meena looked at me and while the chaos surged around us, neither of us moved.

‘Let go,’ she said. And I didn’t understand fast enough, so she pulled her hand from mine and ran into the crowd.

‘Meena!’

I went after her.

I scrabbled down the steps and picked up my open suitcase. I bundled skirts and dresses and shoes back inside. And I stopped at the balloon on the bottom step. The yellow one. We had had as much fun popping all of the yellow balloons as we did living with them buttercupping our bedsit for a week. I’d kept one of the deflated balloons, with its string still attached to it. Because I didn’t want to forget that she had remembered.

The chaos was getting worse. I passed a man who was bleeding from his nose in great rivers down to his lips, so that he had to spit the blood pooling into his mouth onto the floor.

She was quick, darting between people and under signs.

‘Meena!’

A policeman brought his truncheon down on the shoulder of a protester who disappeared out of sight. His friends launched at the officer, grabbing his jacket and pulling him to the ground.

On the Pathé news later, the reporter would call it the most violent protest ever seen in London.

The photographs had slid out of the suitcase and fallen face-down on the pavement. I had only packed two. A photograph of me in a green dress, dancing with Meena at a cèilidh her friend Sally had thrown on my first New Year’s Eve in London. Meena’s laughing and we’re dancing, arms crossed and held together while we spin. It was one of the nights when I had marvelled at how happy it was possible to be. And my favourite photograph: Meena and I, our faces painted with flowers, at the house party of someone or other. The night we had saved the dog. And she had shown me that I wasn’t the only soul she was teaching to set themselves free.

I picked them both up and sat back down on the steps. I guessed it was probably around three in the morning. But still I waited.

A horse bayed and whinnied with fright as his police rider tried to control him. More smoke bombs were set off as officers and protesters were carried away on stretchers.

‘Meena!’ I tried shouting, though I couldn’t hear my own voice. She must have been so far ahead now. And probably still running.

Someone cracked into my head with a heavy sign, and for a moment everything went blurry. White smoke was rising up and I had the feeling I wasn’t really there at all. Then I felt the full force of someone falling onto me and I remember hitting the ground.

I didn’t hear her footsteps, but there she was at the bottom of the steps, draped in a stranger’s coat and carrying a sign that said Peace. Not a scratch on her.

I wondered at how she could be none the worse for the experience.

Her eyes journeyed up my bruised shins to my bloodied knee, to the scratches on my arms, and then, finally, to the suitcases beside me.

There were so many things I wanted to say to her. I wanted to ask her why she could be so free in so many ways but one. Tell her that she needn’t be afraid of me. Explain that I felt for her in a way that I never felt for Johnny, because the way I felt for her wasn’t born of obligation. It was completely and wholly voluntary. And that I could love her for ever, if only she would let me.

But no words came out.

I could taste metal and blood, but I kept walking on and on, in the opposite direction of the protest. I found a side street and then another. As I kept walking down the road, now littered with missiles that had been thrown – rocks, shoes and discarded signs – I saw the smiling face of President Ho Chi Minh once more, now lying on the ground and marked with brown where disrespectful shoes had trampled over him. Go, he told me, go home!

But I didn’t have a home.

So, I would have to find one.

Meena sat beside me on the cold step and rested her head on my shoulder and we didn’t say anything. I didn’t have the bravery to say it again. And I didn’t have the bravery not to hear it back.

At some point I must have slipped into sleep, because when I opened my eyes, the sky had turned from darkness to a hopeful grey. The sun was coming. She was still there, her head resting on my shoulder, dreaming.

I went to stretch out my legs to get the feeling back into them, and my movement must have woken her.

Comments (0)