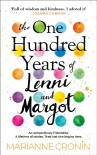

The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot by Marianne Cronin (e reader books txt) 📗

- Author: Marianne Cronin

Book online «The One Hundred Years of Lenni and Margot by Marianne Cronin (e reader books txt) 📗». Author Marianne Cronin

‘So, Margot, what brings you here?’

‘You were standing in the middle of the road and I broke my car trying not to kill you.’

‘No, what brings you to Henley-in-Arden?’

I didn’t say anything.

‘The country life?’

‘No.’

‘The isolation?’

I laughed. ‘No.’

‘The Bard?’

‘I never cared much for Shakespeare.’

‘Never cared much for Shakespeare?’ he repeated.

‘No.’

At this Humphrey James roared with laughter, and in between gasps for breath he said, ‘That is the greatest thing I’ve ever heard!’

We continued walking. The night was bitterly cold, but I didn’t mind it.

‘And what do you do?’ I asked. ‘When you’re not stargazing on the road?’

‘Oh, this and that. Mostly stars.’

‘Mostly stars?’

‘Exactly.’

He stopped, so I stopped too. He pointed to the sky. ‘Every star you see up there,’ he said, ‘is bigger than the sun.’

‘Is that so?’

‘Oh yes, and brighter too. The faint ones might be the same size as the sun, but the brighter ones are bigger. People don’t realize that – they think that because they seem small and twinkling they are small, but they are large, massive, and so very powerful.’

‘Gosh.’

‘You, Margot, you can see approximately twenty quadrillion miles tonight.’

‘Can I? I sometimes have trouble making out road signs without my glasses on.’

‘You can see the stars, can’t you?’

‘I can.’

‘Then you can see twenty quadrillion miles.’

I smiled at him. He smiled at me.

We carried on walking until we reached the railway bridge that announced the beginning of Henley-in-Arden and the end of the wildness.

‘Which way is home?’ he asked, and I pointed.

‘I have to visit a friend that way,’ he said. ‘Would you mind the company?’

‘Not at all,’ I said.

So we took up walking again, this time both of us on the pavement. He pulled a white handkerchief from his pocket and wiped his nose with it.

‘So, Scotland, of course,’ he said. ‘But also, perhaps London?’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘London? You’ve got a twinge to your accent.’

‘Oh, yes. I’ve been living in London.’

‘For how long?’

‘Oh, about twelve years.’

‘Wonderful city,’ he said. ‘Incredible libraries, and the universities are really first rate.’

‘Have you lived there too?’

‘No, but I visit occasionally. I could never live there, I couldn’t bear the visibility.’

We turned onto the high street, and the town seemed to be waiting in a calm, quiet glow.

‘Which way are you?’ he asked.

‘Just along here,’ I gestured.

‘And what do you do now?’ he asked.

‘I work at the Redditch library,’ I said.

‘Ah, so it’s words, then?’

‘Sorry?’

‘It’s words that you do.’

‘I suppose …’

‘Yet not a fan of Shakespeare,’ he said, as though he were piecing together clues in a mystery and this one didn’t fit. I think he was impressed. Incredulous, at least, that I could be one and not the other.

‘It’s not a requirement …’

‘You’re controversial, aren’t you, Margot?’ he asked. ‘A rebel?’

‘Um, I don’t—’

‘Nothing wrong with that!’ he shouted. ‘All the best people are.’

Then he paused and we walked in silence for a moment. I pulled my keys from my handbag.

‘This is where I leave you, then,’ he concluded, as I selected my door key with freezing fingers.

‘Yes,’ I told him.

‘I will have your car collected first thing in the morning,’ he said. ‘What time do you leave for work?’

‘Eight.’

‘In that case, your car will be back here by seven, in full working order.’

‘Will it?’

‘Oh, ye of little faith.’ He laughed.

I opened my door and felt the need to thank him, although I couldn’t work out what I would thank him for. The interruption to my evening and the damage to my car were all his fault, and yet I felt as though I were in some way in his debt, perhaps for the company, for the first non-transactional conversation I’d had in months … or perhaps for the promise of a mended car.

‘Thank you,’ I said.

He smiled and bobbed his head. ‘Goodnight.’ As I let myself into the flat, I heard him shout, ‘Never cared much for Shakespeare!’ as he walked away down the street, laughing.

The next morning, I opened my front door to find that my car had not only been delivered to the parking space outside my flat, but that the engine had been repaired and started like a dream. On the passenger seat sat an envelope. The letter addressed me as ‘the kind-hearted woman who went out of her way not to kill me’, and asked if it would not be too forward to invite me to share in some tapas and stargazing at my earliest convenience. And then, ‘because you are a woman who likes words, Margot,’ he wrote, ‘a poem from my world to yours’.

And in his arachnid writing, he had copied out the first verses of a poem:

Reach me down my Tycho Brahe, I would know him when we meet,

When I share my later science, sitting humbly at his feet;

He may know the law of all things, yet be ignorant of how

We are working to completion, working on from then to now.

Pray, remember, that I leave you all my theory complete,

Lacking only certain data for your adding, as is meet;

And remember, men will scorn it, ’tis original and true,

And the obloquy of newness may fall bitterly on you.

But, my pupil, as my pupil, you have learned the worth of scorn;

You have laughed with me at pity, we have joyed to be forlorn;

What, for us, are all distractions of men’s fellowship and smiles?

What, for us, the goddess Pleasure with her meretricious wiles?

You may tell that German college that their honour comes too late.

But they must not waste repentance on the grizzly savant’s fate;

Though my soul may set in darkness, it will rise in perfect light;

I have loved the stars too fondly to be

Comments (0)