His Masterpiece - Émile Zola (ebook reader 8 inch .txt) 📗

- Author: Émile Zola

Book online «His Masterpiece - Émile Zola (ebook reader 8 inch .txt) 📗». Author Émile Zola

When Claude found himself once more on the pavement of Paris he was seized with a feverish longing for hubbub and motion, a desire to gad about, scour the whole city, and see his chums. He was off the moment he awoke, leaving Christine to get things shipshape by herself in the studio which they had taken in the Rue de Douai, near the Boulevard de Clichy. In this way, on the second day of his arrival, he dropped in at Mahoudeau’s at eight o’clock in the morning, in the chill, grey November dawn which had barely risen.

However, the shop in the Rue du Cherche-Midi, which the sculptor still occupied, was open, and Mahoudeau himself, half asleep, with a white face, was shivering as he took down the shutters.

“Ah! it’s you. The devil! you’ve got into early habits in the country. So it’s settled—you are back for good?”

“Yes; since the day before yesterday.”

“That’s all right. Then we shall see something of each other. Come in; it’s sharp this morning.”

But Claude felt colder in the shop than outside. He kept the collar of his coat turned up, and plunged his hands deep into his pockets; shivering before the dripping moisture of the bare walls, the muddy heaps of clay, and the pools of water soddening the floor. A blast of poverty had swept into the place, emptying the shelves of the casts from the antique, and smashing stands and buckets, which were now held together with bits of rope. It was an abode of dirt and disorder, a mason’s cellar going to rack and ruin. On the window of the door, besmeared with whitewash, there appeared in mockery, as it were, a large beaming sun, roughly drawn with thumb-strokes, and ornamented in the centre with a face, the mouth of which, describing a semicircle, seemed likely to burst with laughter.

“Just wait,” said Mahoudeau, “a fire’s being lighted. These confounded workshops get chilly directly, with the water from the covering cloths.”

At that moment, Claude, on turning round, noticed Chaîne on his knees near the stove, pulling the straw from the seat of an old stool to light the coals with. He bade him good morning, but only elicited a muttered growl, without succeeding in making him look up.

“And what are you doing just now, old man?” he asked the sculptor.

“Oh! nothing of much account. It’s been a bad year—worse than the last one, which wasn’t worth a rap. There’s a crisis in the church-statue business. Yes, the market for holy wares is bad, and, dash it, I’ve had to tighten my belt! Look, in the meanwhile, I’m reduced to this.”

He thereupon took the linen wraps off a bust, showing a long face still further elongated by whiskers, a face full of conceit and infinite imbecility.

“It’s an advocate who lives near by. Doesn’t he look repugnant, eh? And the way he worries me about being very careful with his mouth. However, a fellow must eat, mustn’t he?”

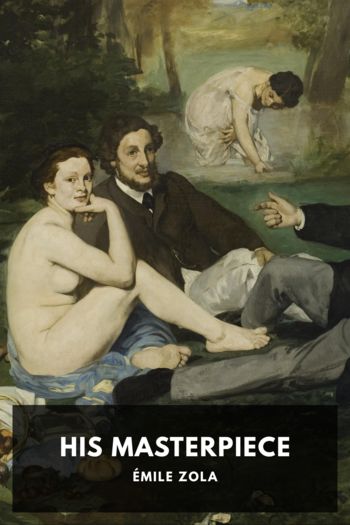

He certainly had an idea for the Salon; an upright figure, a girl about to bathe, dipping her foot in the water, and shivering at its freshness with that slight shiver that renders a woman so adorable. He showed Claude a little model of it, which was already cracking, and the painter looked at it in silence, surprised and displeased at certain concessions he noticed in it: a sprouting of prettiness from beneath a persistent exaggeration of form, a natural desire to please, blended with a lingering tendency to the colossal. However, Mahoudeau began lamenting; an upright figure was no end of a job. He would want iron braces that cost money, and a modelling frame, which he had not got; in fact, a lot of appliances. So he would, no doubt, decide to model the figure in a recumbent attitude beside the water.

“Well, what do you say—what do you think of it?” he asked.

“Not bad,” answered the painter at last. “A little bit sentimental, in spite of the strapping limbs; but it’ll all depend upon the execution. And put her upright, old man; upright, for there would be nothing in it otherwise.”

The stove was roaring, and Chaîne, still mute, rose up. He prowled about for a minute, entered the dark back shop, where stood the bed that he shared with Mahoudeau, and then reappeared, his hat on his head, but more silent, it seemed, than ever. With his awkward peasant fingers he leisurely took up a stick of charcoal and then wrote on the wall: “I am going to buy some tobacco; put some more coals in the stove.” And forthwith he went out.

Claude, who had watched him writing, turned to the other in amazement.

“What’s up?”

“We no longer speak to one another; we write,” said the sculptor, quietly.

“Since when?”

“Since three months ago.”

“And you sleep together?”

“Yes.”

Claude burst out laughing. Ah! dash it all! they must have hard nuts. But what was the reason of this falling-out? Then Mahoudeau vented his rage against that brute of a Chaîne! Hadn’t he, one night on coming home unexpectedly, found him treating Mathilde, the herbalist woman, to a pot of jam? No, he would never forgive him for treating himself in that dirty fashion to delicacies on the sly, while he, Mahoudeau, was half starving, and eating dry bread. The deuce! one ought to share and share alike.

And the grudge had now lasted for nearly three months without a break, without an explanation. They had arranged their lives accordingly; they had reduced their strictly necessary intercourse to a series of short phrases charcoaled on the walls. As for the rest, they lived as before, sharing the same bed in the back shop. After all, there was no need for so much talk in life, people managed to understand one another all the

Comments (0)