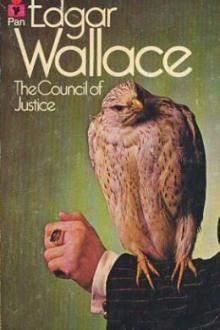

The Council of Justice - Edgar Wallace (best autobiographies to read TXT) 📗

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Book online «The Council of Justice - Edgar Wallace (best autobiographies to read TXT) 📗». Author Edgar Wallace

of the others.

‘I have received no letter,’ he said with an easy laugh—‘only

these.’ He fumbled in his waistcoat pocket and produced two beans.

There was nothing peculiar in these save one was a natural black and

the other had been dyed red.

‘What do they mean?’ demanded Starque suspiciously.

‘I have not the slightest idea,’ said Bartholomew with a

contemptuous smile; ‘they came in a little box, such as jewellery is

sent in, and were unaccompanied either by letter or anything of the

kind. These mysterious messages do not greatly alarm me.’

‘But what does it mean?’ persisted Starque, and every neck was

craned toward the seeds; ‘they must have some significance—think.’

Bartholomew yawned.

‘So far as I know, they are beyond explanation,’ he said carelessly;

‘neither red nor black beans have played any conspicuous part in my

life, so far as I—’

He stopped short and they saw a wave of colour rush to his face,

then die away, leaving it deadly pale.

‘Well?’ demanded Starque; there was a menace in the question.

‘Let me see,’ faltered Bartholomew, and he took up the red bean with

a hand that shook.

He turned it over and over in his hand, calling up his reserve of

strength.

He could not explain, that much he realized.

The explanation might have been possible had he realized earlier the

purport of the message he had received, but now with six pairs of

suspicious eyes turned upon him, and with his confusion duly noted his

hesitation would tell against him.

He had to invent a story that would pass muster.

‘Years ago,’ he began, holding his voice steady, ‘I was a member of

such an organization as this: and—and there was a traitor.’ The story

was plain to him now, and he recovered his balance. ‘The traitor was

discovered and we balloted for his life. There was an equal number for

death and immunity, and I as president had to give the casting vote. A

red bean was for life and a black for death—and I cast my vote for

the man’s death.’

He saw the impression his invention had created and elaborated the

story. Starque, holding the red bean in his hand, examined it

carefully.

‘I have reason to think that by my action I made many enemies, one

of whom probably sent this reminder.’ He breathed an inward sigh of

relief as he saw the clouds of doubt lifting from the faces about him.

Then—

‘And the �1,000?’ asked Starque quietly.

Nobody saw Bartholomew bite his lip, because his hand was caressing

his soft black moustache. What they all observed was the well simulated

surprise expressed in the lift of his eyebrows.

‘The thousand pounds?’ he said puzzled, then he laughed. ‘Oh, I see

you, too, have heard the story—we found the traitor had accepted that

sum to betray us—and this we confiscated for the benefit of the

Society—and rightly so,’ he added, indignantly.

The murmur of approbation relieved him of any fear as to the result

of his explanation. Even Starque smiled.

‘I did not know the story,’ he said, ‘but I did see the

“�1,000” which had been scratched on the side of the

red bean; but this brings us no nearer to the solution of the mystery.

Who has betrayed us to the Four Just Men?’

There came, as he spoke, a gentle tapping on the door of the room.

Francois, who sat at the president’s right hand, rose stealthily and

tiptoed to the door.

‘Who is there?’ he asked in a low voice.

Somebody spoke in German, and the voice carried so that every man

knew the speaker.

‘The Woman of Gratz,’ said Bartholomew, and in his eagerness he rose

to his feet.

If one sought for the cause of friction between Starque and the

ex-captain of Irregular Cavalry, here was the end of the search. The

flame that came to the eyes of these two men as she entered the room

told the story.

Starque, heavily made, animal man to his fingertips, rose to greet

her, his face aglow.

‘Madonna,’ he murmured, and kissed her hand.

She was dressed well enough, with a rich sable coat that fitted

tightly to her sinuous figure, and a fur toque upon her beautiful

head.

She held a gloved hand toward Bartholomew and smiled.

Bartholomew, like his rival, had a way with women; but it was a

gentle way, overladen with Western conventions and hedged about with

set proprieties. That he was a contemptible villain according to our

conceptions is true, but he had received a rudimentary training in the

world of gentlemen. He had moved amongst men who took their hats off to

their womenkind, and who controlled their actions by a nebulous code.

Yet he behaved with greater extravagance than did Starque, for he held

her hand in his, looking into her eyes, whilst Starque fidgeted

impatiently.

‘Comrade,’ at last he said testily, ‘we will postpone our talk with

our little Maria. It would be bad for her to think that she is holding

us from our work—and there are the Four—’

He saw her shiver.

‘The Four?’ she repeated. ‘Then they have written to you, also?’

Starque brought his fist with a crash down on the table.

‘You—you! They have dared threaten you? By Heaven—’

‘Yes,’ she went on, and it seemed that her rich sweet voice grew a

little husky; ‘they have threatened—me.’

She loosened the furs at her throat as though the room had suddenly

become hot and the atmosphere unbreathable.

The torrent of words that came tumbling to the lips of Starque was

arrested by the look in her face.

‘It isn’t death that I fear,’ she went on slowly; ‘indeed, I

scarcely know what I fear.’

Bartholomew, superficial and untouched by the tragic mystery of her

voice, broke in upon their silence. For silenced they were by the

girl’s distress.

‘With such men as we about, why need you notice the theatrical play

of these Four Just Men?’ he asked, with a laugh; then he remembered the

two little beans and became suddenly silent with the rest.

So complete and inexplicable was the chill that had come to them

with the pronouncement of the name of their enemy, and so absolutely

did the spectacle of the Woman of Gratz on the verge of tears move

them, that they heard then what none had heard before—the ticking of

the clock.

It was the habit of many years that carried Bartholomew’s hand to

his pocket, mechanically he drew out his watch, and automatically he

cast his eyes about the room for the clock wherewith to check the

time.

It was one of those incongruous pieces of commonplace that intrude

upon tragedy, but it loosened the tongues of the council, and they all

spoke together.

It was Starque who gathered the girl’s trembling hands between his

plump palms.

‘Maria, Maria,’ he chided softly, ‘this is folly. What! the Woman of

Gratz who defied all Russia—who stood before Mirtowsky and bade him

defiance—what is it?’

The last words were sharp and angry and were directed to

Bartholomew.

For the second time that night the Englishman’s face was white, and

he stood clutching the edge of the table with staring eyes and with his

lower jaw drooping.

‘God, man!’ cried Starque, seizing him by the arm, ‘what is it—

speak—you are frightening her!’

‘The clock!’ gasped Bartholomew in a hollow voice, ‘where—where

is the clock?’

His staring eyes wandered helplessly from side to side. ‘Listen,’ he

whispered, and they held their breath. Very plainly indeed did they

hear the ‘tick—tick—tick.’

‘It is under the table,’ muttered Francois.

Starque seized the cloth and lifted it. Underneath, in the shadow,

he saw the black box and heard the ominous whir of clockwork. ‘Out!’ he

roared and sprang to the door. It was locked and from the outside.

Again and again he flung his huge bulk against the door, but the men

who pressed round him, whimpering and slobbering in their pitiable

fright, crowded about him and gave him no room.

With his strong arms he threw them aside left and right; then leapt

at the door, bringing all his weight and strength to bear, and the door

crashed open.

Alone of the party the Woman of Gratz preserved her calm. She stood

by the table, her foot almost touching the accursed machine, and she

felt the faint vibrations of its working. Then Starque caught her up in

his arms and through the narrow passage he half led, half carried her,

till they reached the street in safety.

The passing pedestrians saw the dishevelled group, and, scenting

trouble, gathered about them.

‘What was it? What was it?’ whispered Francois, but Starque pushed

him aside with a snarl.

A taxi was passing and he called it, and lifting the girl inside, he

shouted directions and sprang in after her.

As the taxi whirled away, the bewildered Council looked from one to

the other.

They had left the door of the house wide open and in the hall a

flickering gas-jet gyrated wildly.

‘Get away from here,’ said Bartholomew beneath his breath.

‘But the papers—the records,’ said the other wringing his

hands.

Bartholomew thought quickly.

The records were such as could not be left lying about with

impunity. For all he knew these madmen had implicated him in their

infernal writings. He was not without courage, but it needed all he

possessed to re-enter the room where a little machine in a black box

ticked mysteriously.

‘Where are they?’ he demanded.

‘On the table,’ almost whispered the other. ‘Mon Dieux! what

disaster!’ The Englishman made up his mind.

He sprang up the three steps into the hall. Two paces brought him to

the door, another stride to the table. He heard the ‘tick’ of the

machine, he gave one glance to the table and another to the floor, and

was out again in the street before he had taken two long breaths.

Francois stood waiting, the rest of the men had disappeared.

‘The papers! the papers!’ cried the Frenchman.

‘Gone!’ replied Bartholomew between his teeth.

Less than a hundred yards away another conference was being

held.

‘Manfred,’ said Poiccart suddenly—there had been a lull in the

talk—‘shall we need our friend?’ Manfred smiled. ‘Meaning the

admirable Mr. Jessen?’

Poiccart nodded.

‘I think so,’ said Manfred quietly; ‘I am not so sure that the cheap

alarm-clock we put in the biscuit box will be a sufficient warning to

the Inner Council—here is Leon.’

Gonsalez walked into the room and removed his overcoat

deliberately.

Then they saw that the sleeve of his dress coat was torn, and

Manfred remarked the stained handkerchief that was lightly bound round

one hand.

‘Glass,’ explained Gonsalez laconically. ‘I had to scale a

wall.’

‘Well?’ asked Manfred.

‘Very well,’ replied the other; ‘they bolted like sheep, and I had

nothing to do but to walk in and carry away the extremely interesting

record of sentences they have passed.’

‘What of Bartholomew?’ Gonsalez was mildly amused. ‘He was less

panicky than the rest—he came back to look for the papers.’

‘Will he—?’

‘I think so,’ said Leon. ‘I noticed he left the black bean behind

him in his flight—so I presume we shall see the red.’

‘It will simplify matters,’ said Manfred gravely.

CHAPTER V. The Council of Justice

Lauder Bartholomew knew a man

Comments (0)