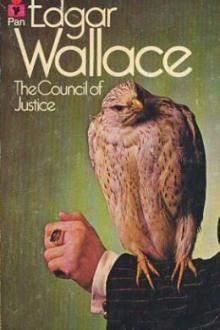

The Council of Justice - Edgar Wallace (best autobiographies to read TXT) 📗

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Book online «The Council of Justice - Edgar Wallace (best autobiographies to read TXT) 📗». Author Edgar Wallace

The Council of Justice

Edgar Wallace

1908

CHAPTER I. The Red Hundred

It is not for you or me to judge Manfred and his works. I say

‘Manfred’, though I might as well have said ‘Gonsalez’, or for the

matter of that ‘Poiccart’, since they are equally guilty or great

according to the light in which you view their acts. The most lawless

of us would hesitate to defend them, but the greater humanitarian could

scarcely condemn them.

From the standpoint of us, who live within the law, going about our

business in conformity with the code, and unquestioningly keeping to

the left or to the right as the police direct, their methods were

terrible, indefensible, revolting.

It does not greatly affect the issue that, for want of a better

word, we call them criminals. Such would be mankind’s unanimous

designation, but I think—indeed, I know—that they were indifferent to

the opinions of the human race. I doubt very much whether they expected

posterity to honour them.

Their action towards the cabinet minister was murder, pure and

simple. Yet, in view of the large humanitarian problems involved, who

would describe it as pernicious?

Frankly I say of the three men who killed Sir Philip Ramon, and who

slew ruthlessly in the name of Justice, that my sympathies are with

them. There are crimes for which there is no adequate punishment, and

offences that the machinery of the written law cannot efface. Therein

lies the justification for the Four Just Men,—the Council of Justice

as they presently came to call themselves a council of great

intellects, passionless.

And not long after the death of Sir Philip and while England still

rang with that exploit, they performed an act or a series of acts that

won not alone from the Government of Great Britain, but from the

Governments of Europe, a sort of unofficial approval and Falmouth had

his wish. For here they waged war against great world-criminals—they

pitted their strength, their cunning, and their wonderful intellects

against the most powerful organization of the underworld—against past

masters of villainous arts, and brains equally agile.

It was the day of days for the Red Hundred. The wonderful

international congress was meeting in London, the first great congress

of recognized Anarchism. This was no hole-and-corner gathering of

hurried men speaking furtively, but one open and unafraid with three

policemen specially retained for duty outside the hall, a

commissionaire to take tickets at the outer lobby, and a shorthand

writer with a knowledge of French and Yiddish to make notes of

remarkable utterances.

The wonderful congress was a fact. When it had been broached there

were people who laughed at the idea; Niloff of Vitebsk was one because

he did not think such openness possible. But little Peter (his

preposterous name was Konoplanikova, and he was a reporter on the staff

of the foolish Russkoye Znamza), this little Peter who had

thought out the whole thing, whose idea it was to gather a conference

of the Red Hundred in London, who hired the hall and issued the bills

(bearing in the top left-hand corner the inverted triangle of the

Hundred) asking those Russians in London interested in the building of

a Russian Sailors’ Home to apply for tickets, who, too, secured a hall

where interruption was impossible, was happy—yea, little brothers, it

was a great day for Peter.

‘You can always deceive the police,’ said little Peter

enthusiastically; ‘call a meeting with a philanthropic object

and—voila!’

Wrote Inspector Falmouth to the assistant commissioner of police:—

Your respected communication to hand. The meeting to be held tonight

at the Phoenix Hall, Middlesex Street, E., with the object of raising

funds for a Russian Sailors’ Home is, of course, the first

international congress of the Red Hundred. Shall not be able to get a

man inside, but do not think that matters much, as meeting will be

engaged throwing flowers at one another and serious business will not

commence till the meeting of the inner committee. I inclose a list of

men already arrived in London, and have the honour to request that you

will send me portraits of under-mentioned men.

There were three delegates from Baden, Herr Schmidt from Frieburg,

Herr Bleaumeau from Karlsruhe, and Herr Von Dunop from Mannheim. They

were not considerable persons, even in the eyes of the world of

Anarchism; they called for no particular notice, and therefore the

strange thing that happened to them on the night of the congress is all

the more remarkable.

Herr Schmidt had left his pension in Bloomsbury and was

hurrying eastward. It was a late autumn evening and a chilly rain fell,

and Herr Schmidt was debating in his mind whether he should go direct

to the rendezvous where he had promised to meet his two compatriots, or

whether he should call a taxi and drive direct to the hall, when a hand

grasped his arm.

He turned quickly and reached for his hip pocket. Two men stood

behind him and but for themselves the square through which he was

passing was deserted.

Before he could grasp the Browning pistol, his other arm was seized

and the taller of the two men spoke.

‘You are Augustus Schmidt?’ he asked.

‘That is my name.’

‘You are an anarchist?’

‘That is my affair.’

‘You are at present on your way to a meeting of the Red

Hundred?’

Herr Schmidt opened his eyes in genuine astonishment.

‘How did you know that?’ he asked.

‘I am Detective Simpson from Scotland Yard, and I shall take you

into custody,’ was the quiet reply.

‘On what charge?’ demanded the German.

‘As to that I shall tell you later.’

The man from Baden shrugged his shoulders.

‘I have yet to learn that it is an offence in England to hold

opinions.’

A closed motor-car entered the square, and the shorter of the two

whistled and the chauffeur drew up near the group.

The anarchist turned to the man who had arrested him.

‘I warn you that you shall answer for this,’ he said wrathfully. ‘I

have an important engagement that you have made me miss through your

foolery and—’

‘Get in!’ interrupted the tall man tersely.

Schmidt stepped into the car and the door snapped behind him.

He was alone and in darkness. The car moved on and then Schmidt

discovered that there were no windows to the vehicle. A wild idea came

to him that he might escape. He tried the door of the car; it was

immovable. He cautiously tapped it. It was lined with thin sheets of

steel.

‘A prison on wheels,’ he muttered with a curse, and sank back into

the corner of the car.

He did not know London; he had not the slightest idea where he was

going. For ten minutes the car moved along. He was puzzled. These

policemen had taken nothing from him, he still retained his pistol.

They had not even attempted to search him for compromising documents.

Not that he had any except the pass for the conference and—the Inner

Code!

Heavens! He must destroy that. He thrust his hand into the inner

pocket of his coat. It was empty. The thin leather case was gone! His

face went grey, for the Red Hundred is no fanciful secret society but a

bloody-minded organization with less mercy for bungling brethren than

for its sworn enemies. In the thick darkness of the car his nervous

fingers groped through all his pockets. There was no doubt at all—the

papers had gone.

In the midst of his search the car stopped. He slipped the flat

pistol from his pocket. His position was desperate and he was not the

kind of man to shirk a risk.

Once there was a brother of the Red Hundred who sold a password to

the Secret Police. And the brother escaped from Russia. There was a

woman in it, and the story is a mean little story that is hardly worth

the telling. Only, the man and the woman escaped, and went to Baden,

and Schmidt recognized them from the portraits he had received from

headquarters, and one night…You understand that there was nothing

clever or neat about it. English newspapers would have described it as

a ‘revolting murder’, because the details of the crime were rather

shocking. The thing that stood to Schmidt’s credit in the books of the

Society was that the murderer was undiscovered.

The memory of this episode came back to the anarchist as the car

stopped—perhaps this was the thing the police had discovered? Out of

the dark corners of his mind came the scene again, and the voice of the

man…‘Don’t! don’t! O Christ! don’t!’ and Schmidt sweated…

The door of the car opened and he slipped back the cover of his

pistol.

‘Don’t shoot,’ said a quiet voice in the gloom outside, ‘here are

some friends of yours.’

He lowered his pistol, for his quick ears detected a wheezing

cough.

‘Von Dunop!’ he cried in astonishment.

‘And Herr Bleaumeau,’ said the same voice. ‘Get in, you two.’

Two men stumbled into the car, one dumbfounded and silent—save for

the wheezing cough—the other blasphemous and voluble.

‘Wait, my friend!’ raved the bulk of Bleaumeau; ‘wait! I will make

you sorry.’

The door shut and the car moved on.

The two men outside watched the vehicle with its unhappy passengers

disappear round a corner and then walked slowly away.

‘Extraordinary men,’ said the taller.

‘Most,’ replied the other, and then, ‘Von Dunop—isn’t he—?’

‘The man who threw the bomb at the Swiss President—yes.’

The shorter man smiled in the darkness.

‘Given a conscience, he is enduring his hour,’ he said.

The pair walked on in silence and turned into Oxford Street as the

clock of a church struck eight.

The tall man lifted his walking-stick and a sauntering taxi pulled

up at the curb.

‘Aldgate,’ he said, and the two men took their seats.

Not until the taxi was spinning along Newgate Street did either of

the men speak, and then the shorter asked:

‘You are thinking about the woman?’

The other nodded and his companion relapsed into silence; then he

spoke again:

‘She is a problem and a difficulty, in a way—yet she is the most

dangerous of the lot. And the curious thing about it is that if she

were not beautiful and young she would not be a problem at all. We’re

very human, George. God made us illogical that the minor businesses of

life should not interfere with the great scheme. And the great scheme

is that animal men should select animal women for the mothers of their

children.’

‘Venenum in auro bibitur,’ the other quoted, which shows that

he was an extraordinary detective, ‘and so far as I am concerned it

matters little to me whether an irresponsible homicide is a beautiful

woman or a misshapen negro.’

They dismissed the taxi at Aldgate Station and turned into Middlesex

Street.

The meeting-place of the great congress was a hall which was

originally erected by an enthusiastic Christian gentleman with a

weakness for the conversion of Jews to the New Presbyterian Church,

Comments (0)