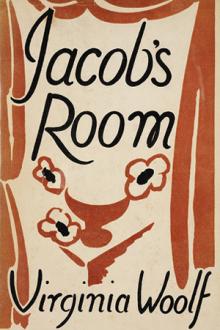

Jacob's Room - Virginia Woolf (polar express read aloud txt) 📗

- Author: Virginia Woolf

- Performer: 0140185704

Book online «Jacob's Room - Virginia Woolf (polar express read aloud txt) 📗». Author Virginia Woolf

a parrot, believed in the transmigration of souls, and could read the

future in tea leaves. Dirty lodging-house wallpaper she was behind the

chastity of Florinda.

Now Florinda wept, and spent the day wandering the streets; stood at

Chelsea watching the river swim past; trailed along the shopping

streets; opened her bag and powdered her cheeks in omnibuses; read love

letters, propping them against the milk pot in the A.B.C. shop; detected

glass in the sugar bowl; accused the waitress of wishing to poison her;

declared that young men stared at her; and found herself towards evening

slowly sauntering down Jacob’s street, when it struck her that she liked

that man Jacob better than dirty Jews, and sitting at his table (he was

copying his essay upon the Ethics of Indecency), drew off her gloves and

told him how Mother Stuart had banged her on the head with the tea-cosy.

Jacob took her word for it that she was chaste. She prattled, sitting by

the fireside, of famous painters. The tomb of her father was mentioned.

Wild and frail and beautiful she looked, and thus the women of the

Greeks were, Jacob thought; and this was life; and himself a man and

Florinda chaste.

She left with one of Shelley’s poems beneath her arm. Mrs. Stuart, she

said, often talked of him.

Marvellous are the innocent. To believe that the girl herself transcends

all lies (for Jacob was not such a fool as to believe implicitly), to

wonder enviously at the unanchored life—his own seeming petted and even

cloistered in comparison—to have at hand as sovereign specifics for all

disorders of the soul Adonais and the plays of Shakespeare; to figure

out a comradeship all spirited on her side, protective on his, yet equal

on both, for women, thought Jacob, are just the same as men—innocence

such as this is marvellous enough, and perhaps not so foolish after all.

For when Florinda got home that night she first washed her head; then

ate chocolate creams; then opened Shelley. True, she was horribly bored.

What on earth was it ABOUT? She had to wager with herself that she would

turn the page before she ate another. In fact she slept. But then her

day had been a long one, Mother Stuart had thrown the tea-cosy;—there

are formidable sights in the streets, and though Florinda was ignorant

as an owl, and would never learn to read even her love letters

correctly, still she had her feelings, liked some men better than

others, and was entirely at the beck and call of life. Whether or not

she was a virgin seems a matter of no importance whatever. Unless,

indeed, it is the only thing of any importance at all.

Jacob was restless when she left him.

All night men and women seethed up and down the well-known beats. Late

home-comers could see shadows against the blinds even in the most

respectable suburbs. Not a square in snow or fog lacked its amorous

couple. All plays turned on the same subject. Bullets went through heads

in hotel bedrooms almost nightly on that account. When the body escaped

mutilation, seldom did the heart go to the grave unscarred. Little else

was talked of in theatres and popular novels. Yet we say it is a matter

of no importance at all.

What with Shakespeare and Adonais, Mozart and Bishop Berkeley—choose

whom you like—the fact is concealed and the evenings for most of us

pass reputably, or with only the sort of tremor that a snake makes

sliding through the grass. But then concealment by itself distracts the

mind from the print and the sound. If Florinda had had a mind, she might

have read with clearer eyes than we can. She and her sort have solved

the question by turning it to a trifle of washing the hands nightly

before going to bed, the only difficulty being whether you prefer your

water hot or cold, which being settled, the mind can go about its

business unassailed.

But it did occur to Jacob, half-way through dinner, to wonder whether

she had a mind.

They sat at a little table in the restaurant.

Florinda leant the points of her elbows on the table and held her chin

in the cup of her hands. Her cloak had slipped behind her. Gold and

white with bright beads on her she emerged, her face flowering from her

body, innocent, scarcely tinted, the eyes gazing frankly about her, or

slowly settling on Jacob and resting there. She talked:

“You know that big black box the Australian left in my room ever so long

ago? … I do think furs make a woman look old. … That’s Bechstein

come in now. … I was wondering what you looked like when you were a

little boy, Jacob.” She nibbled her roll and looked at him.

“Jacob. You’re like one of those statues. … I think there are lovely

things in the British Museum, don’t you? Lots of lovely things …” she

spoke dreamily. The room was filling; the heat increasing. Talk in a

restaurant is dazed sleep-walkers’ talk, so many things to look at—so

much noise—other people talking. Can one overhear? Oh, but they mustn’t

overhear US.

“That’s like Ellen Nagle—that girl …” and so on.

“I’m awfully happy since I’ve known you, Jacob. You’re such a GOOD man.”

The room got fuller and fuller; talk louder; knives more clattering.

“Well, you see what makes her say things like that is …”

She stopped. So did every one.

“To-morrow … Sunday … a beastly … you tell me … go then!” Crash!

And out she swept.

It was at the table next them that the voice spun higher and higher.

Suddenly the woman dashed the plates to the floor. The man was left

there. Everybody stared. Then—“Well, poor chap, we mustn’t sit staring.

What a go! Did you hear what she said? By God, he looks a fool! Didn’t

come up to the scratch, I suppose. All the mustard on the tablecloth.

The waiters laughing.”

Jacob observed Florinda. In her face there seemed to him something

horribly brainless—as she sat staring.

Out she swept, the black woman with the dancing feather in her hat.

Yet she had to go somewhere. The night is not a tumultuous black ocean

in which you sink or sail as a star. As a matter of fact it was a wet

November night. The lamps of Soho made large greasy spots of light upon

the pavement. The by-streets were dark enough to shelter man or woman

leaning against the doorways. One detached herself as Jacob and Florinda

approached.

“She’s dropped her glove,” said Florinda.

Jacob, pressing forward, gave it her.

Effusively she thanked him; retraced her steps; dropped her glove again.

But why? For whom? Meanwhile, where had the other woman got to? And the

man?

The street lamps do not carry far enough to tell us. The voices, angry,

lustful, despairing, passionate, were scarcely more than the voices of

caged beasts at night. Only they are not caged, nor beasts. Stop a man;

ask him the way; he’ll tell it you; but one’s afraid to ask him the way.

What does one fear?—the human eye. At once the pavement narrows, the

chasm deepens. There! They’ve melted into it—both man and woman.

Further on, blatantly advertising its meritorious solidity, a boarding-house exhibits behind uncurtained windows its testimony to the soundness

of London. There they sit, plainly illuminated, dressed like ladies and

gentlemen, in bamboo chairs. The widows of business men prove

laboriously that they are related to judges. The wives of coal merchants

instantly retort that their fathers kept coachmen. A servant brings

coffee, and the crochet basket has to be moved. And so on again into the

dark, passing a girl here for sale, or there an old woman with only

matches to offer, passing the crowd from the Tube station, the women

with veiled hair, passing at length no one but shut doors, carved door-posts, and a solitary policeman, Jacob, with Florinda on his arm,

reached his room and, lighting the lamp, said nothing at all.

“I don’t like you when you look like that,” said Florinda.

The problem is insoluble. The body is harnessed to a brain. Beauty goes

hand in hand with stupidity. There she sat staring at the fire as she

had stared at the broken mustard-pot. In spite of defending indecency,

Jacob doubted whether he liked it in the raw. He had a violent reversion

towards male society, cloistered rooms, and the works of the classics;

and was ready to turn with wrath upon whoever it was who had fashioned

life thus.

Then Florinda laid her hand upon his knee.

After all, it was none of her fault. But the thought saddened him. It’s

not catastrophes, murders, deaths, diseases, that age and kill us; it’s

the way people look and laugh, and run up the steps of omnibuses.

Any excuse, though, serves a stupid woman. He told her his head ached.

But when she looked at him, dumbly, half-guessing, half-understanding,

apologizing perhaps, anyhow saying as he had said, “It’s none of my

fault,” straight and beautiful in body, her face like a shell within its

cap, then he knew that cloisters and classics are no use whatever. The

problem is insoluble.

About this time a firm of merchants having dealings with the East put on

the market little paper flowers which opened on touching water. As it

was the custom also to use finger-bowls at the end of dinner, the new

discovery was found of excellent service. In these sheltered lakes the

little coloured flowers swam and slid; surmounted smooth slippery waves,

and sometimes foundered and lay like pebbles on the glass floor. Their

fortunes were watched by eyes intent and lovely. It is surely a great

discovery that leads to the union of hearts and foundation of homes. The

paper flowers did no less.

It must not be thought, though, that they ousted the flowers of nature.

Roses, lilies, carnations in particular, looked over the rims of vases

and surveyed the bright lives and swift dooms of their artificial

relations. Mr. Stuart Ormond made this very observation; and charming it

was thought; and Kitty Craster married him on the strength of it six

months later. But real flowers can never be dispensed with. If they

could, human life would be a different affair altogether. For flowers

fade; chrysanthemums are the worst; perfect over night; yellow and jaded

next morning—not fit to be seen. On the whole, though the price is

sinful, carnations pay best;—it’s a question, however, whether it’s

wise to have them wired. Some shops advise it. Certainly it’s the only

way to keep them at a dance; but whether it is necessary at dinner

parties, unless the rooms are very hot, remains in dispute. Old Mrs.

Temple used to recommend an ivy leaf—just one—dropped into the bowl.

She said it kept the water pure for days and days. But there is some

reason to think that old Mrs. Temple was mistaken.

The little cards, however, with names engraved on them, are a more

serious problem than the flowers. More horses’ legs have been worn out,

more coachmen’s lives consumed, more hours of sound afternoon time

vainly lavished than served to win us the battle of Waterloo, and pay

for it into the bargain. The little demons are the source of as many

reprieves, calamities, and anxieties as the battle itself. Sometimes

Mrs. Bonham has just gone out; at others she is at home. But, even if

the cards should be superseded, which seems unlikely, there are unruly

powers blowing life into storms, disordering

Comments (0)