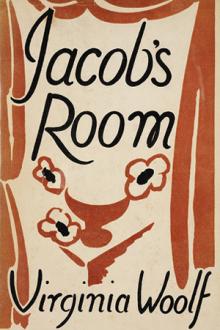

Jacob's Room - Virginia Woolf (polar express read aloud txt) 📗

- Author: Virginia Woolf

- Performer: 0140185704

Book online «Jacob's Room - Virginia Woolf (polar express read aloud txt) 📗». Author Virginia Woolf

furtively at the goddess on the left-hand side holding the roof on her

head. She reminded him of Sandra Wentworth Williams. He looked at her,

then looked away. He looked at her, then looked away. He was

extraordinarily moved, and with the battered Greek nose in his head,

with Sandra in his head, with all sorts of things in his head, off he

started to walk right up to the top of Mount Hymettus, alone, in the

heat.

That very afternoon Bonamy went expressly to talk about Jacob to tea

with Clara Durrant in the square behind Sloane Street where, on hot

spring days, there are striped blinds over the front windows, single

horses pawing the macadam outside the doors, and elderly gentlemen in

yellow waistcoats ringing bells and stepping in very politely when the

maid demurely replies that Mrs. Durrant is at home.

Bonamy sat with Clara in the sunny front room with the barrel organ

piping sweetly outside; the water-cart going slowly along spraying the

pavement; the carriages jingling, and all the silver and chintz, brown

and blue rugs and vases filled with green boughs, striped with trembling

yellow bars.

The insipidity of what was said needs no illustration—Bonamy kept on

gently returning quiet answers and accumulating amazement at an

existence squeezed and emasculated within a white satin shoe (Mrs.

Durrant meanwhile enunciating strident politics with Sir Somebody in the

back room) until the virginity of Clara’s soul appeared to him candid;

the depths unknown; and he would have brought out Jacob’s name had he

not begun to feel positively certain that Clara loved him—and could do

nothing whatever.

“Nothing whatever!” he exclaimed, as the door shut, and, for a man of

his temperament, got a very queer feeling, as he walked through the

park, of carriages irresistibly driven; of flower beds uncompromisingly

geometrical; of force rushing round geometrical patterns in the most

senseless way in the world. “Was Clara,” he thought, pausing to watch

the boys bathing in the Serpentine, “the silent woman?—would Jacob

marry her?”

But in Athens in the sunshine, in Athens, where it is almost impossible

to get afternoon tea, and elderly gentlemen who talk politics talk them

all the other way round, in Athens sat Sandra Wentworth Williams,

veiled, in white, her legs stretched in front of her, one elbow on the

arm of the bamboo chair, blue clouds wavering and drifting from her

cigarette.

The orange trees which flourish in the Square of the Constitution, the

band, the dragging of feet, the sky, the houses, lemon and rose

coloured—all this became so significant to Mrs. Wentworth Williams

after her second cup of coffee that she began dramatizing the story of

the noble and impulsive Englishwoman who had offered a seat in her

carriage to the old American lady at Mycenae (Mrs. Duggan)—not

altogether a false story, though it said nothing of Evan, standing first

on one foot, then on the other, waiting for the women to stop

chattering.

“I am putting the life of Father Damien into verse,” Mrs. Duggan had

said, for she had lost everything—everything in the world, husband and

child and everything, but faith remained.

Sandra, floating from the particular to the universal, lay back in a

trance.

The flight of time which hurries us so tragically along; the eternal

drudge and drone, now bursting into fiery flame like those brief balls

of yellow among green leaves (she was looking at orange trees); kisses

on lips that are to die; the world turning, turning in mazes of heat and

sound—though to be sure there is the quiet evening with its lovely

pallor, “For I am sensitive to every side of it,” Sandra thought, “and

Mrs. Duggan will write to me for ever, and I shall answer her letters.”

Now the royal band marching by with the national flag stirred wider

rings of emotion, and life became something that the courageous mount

and ride out to sea on—the hair blown back (so she envisaged it, and

the breeze stirred slightly among the orange trees) and she herself was

emerging from silver spray—when she saw Jacob. He was standing in the

Square with a book under his arm looking vacantly about him. That he was

heavily built and might become stout in time was a fact.

But she suspected him of being a mere bumpkin.

“There is that young man,” she said, peevishly, throwing away her

cigarette, “that Mr. Flanders.”

“Where?” said Evan. “I don’t see him.”

“Oh, walking away—behind the trees now. No, you can’t see him. But we

are sure to run into him,” which, of course, they did.

But how far was he a mere bumpkin? How far was Jacob Flanders at the age

of twenty-six a stupid fellow? It is no use trying to sum people up. One

must follow hints, not exactly what is said, nor yet entirely what is

done. Some, it is true, take ineffaceable impressions of character at

once. Others dally, loiter, and get blown this way and that. Kind old

ladies assure us that cats are often the best judges of character. A cat

will always go to a good man, they say; but then, Mrs. Whitehorn,

Jacob’s landlady, loathed cats.

There is also the highly respectable opinion that character-mongering is

much overdone nowadays. After all, what does it matter—that Fanny Elmer

was all sentiment and sensation, and Mrs. Durrant hard as iron? that

Clara, owing (so the character-mongers said) largely to her mother’s

influence, never yet had the chance to do anything off her own bat, and

only to very observant eyes displayed deeps of feeling which were

positively alarming; and would certainly throw herself away upon some

one unworthy of her one of these days unless, so the character-mongers

said, she had a spark of her mother’s spirit in her—was somehow heroic.

But what a term to apply to Clara Durrant! Simple to a degree, others

thought her. And that is the very reason, so they said, why she attracts

Dick Bonamy—the young man with the Wellington nose. Now HE’S a dark

horse if you like. And there these gossips would suddenly pause.

Obviously they meant to hint at his peculiar disposition—long rumoured

among them.

“But sometimes it is precisely a woman like Clara that men of that

temperament need…” Miss Julia Eliot would hint.

“Well,” Mr. Bowley would reply, “it may be so.”

For however long these gossips sit, and however they stuff out their

victims’ characters till they are swollen and tender as the livers of

geese exposed to a hot fire, they never come to a decision.

“That young man, Jacob Flanders,” they would say, “so distinguished

looking—and yet so awkward.” Then they would apply themselves to Jacob

and vacillate eternally between the two extremes. He rode to hounds—

after a fashion, for he hadn’t a penny.

“Did you ever hear who his father was?” asked Julia Eliot.

“His mother, they say, is somehow connected with the Rocksbiers,”

replied Mr. Bowley.

“He doesn’t overwork himself anyhow.”

“His friends are very fond of him.”

“Dick Bonamy, you mean?”

“No, I didn’t mean that. It’s evidently the other way with Jacob. He is

precisely the young man to fall headlong in love and repent it for the

rest of his life.”

“Oh, Mr. Bowley,” said Mrs. Durrant, sweeping down upon them in her

imperious manner, “you remember Mrs. Adams? Well, that is her niece.”

And Mr. Bowley, getting up, bowed politely and fetched strawberries.

So we are driven back to see what the other side means—the men in clubs

and Cabinets—when they say that character-drawing is a frivolous

fireside art, a matter of pins and needles, exquisite outlines enclosing

vacancy, flourishes, and mere scrawls.

The battleships ray out over the North Sea, keeping their stations

accurately apart. At a given signal all the guns are trained on a target

which (the master gunner counts the seconds, watch in hand—at the sixth

he looks up) flames into splinters. With equal nonchalance a dozen young

men in the prime of life descend with composed faces into the depths of

the sea; and there impassively (though with perfect mastery of

machinery) suffocate uncomplainingly together. Like blocks of tin

soldiers the army covers the cornfield, moves up the hillside, stops,

reels slightly this way and that, and falls flat, save that, through

field glasses, it can be seen that one or two pieces still agitate up

and down like fragments of broken match-stick.

These actions, together with the incessant commerce of banks,

laboratories, chancellories, and houses of business, are the strokes

which oar the world forward, they say. And they are dealt by men as

smoothly sculptured as the impassive policeman at Ludgate Circus. But

you will observe that far from being padded to rotundity his face is

stiff from force of will, and lean from the efforts of keeping it so.

When his right arm rises, all the force in his veins flows straight from

shoulder to finger-tips; not an ounce is diverted into sudden impulses,

sentimental regrets, wire-drawn distinctions. The buses punctually stop.

It is thus that we live, they say, driven by an unseizable force. They

say that the novelists never catch it; that it goes hurtling through

their nets and leaves them torn to ribbons. This, they say, is what we

live by—this unseizable force.

“Where are the men?” said old General Gibbons, looking round the

drawing-room, full as usual on Sunday afternoons of well-dressed people.

“Where are the guns?”

Mrs. Durrant looked too.

Clara, thinking that her mother wanted her, came in; then went out

again.

They were talking about Germany at the Durrants, and Jacob (driven by

this unseizable force) walked rapidly down Hermes Street and ran

straight into the Williamses.

“Oh!” cried Sandra, with a cordiality which she suddenly felt. And Evan

added, “What luck!”

The dinner which they gave him in the hotel which looks on to the Square

of the Constitution was excellent. Plated baskets contained fresh rolls.

There was real butter. And the meat scarcely needed the disguise of

innumerable little red and green vegetables glazed in sauce.

It was strange, though. There were the little tables set out at

intervals on the scarlet floor with the Greek King’s monogram wrought in

yellow. Sandra dined in her hat, veiled as usual. Evan looked this way

and that over his shoulder; imperturbable yet supple; and sometimes

sighed. It was strange. For they were English people come together in

Athens on a May evening. Jacob, helping himself to this and that,

answered intelligently, yet with a ring in his voice.

The Williamses were going to Constantinople early next morning, they

said.

“Before you are up,” said Sandra.

They would leave Jacob alone, then. Turning very slightly, Evan ordered

something—a bottle of wine—from which he helped Jacob, with a kind of

solicitude, with a kind of paternal solicitude, if that were possible.

To be left alone—that was good for a young fellow. Never was there a

time when the country had more need of men. He sighed.

“And you have been to the Acropolis?” asked Sandra.

“Yes,” said Jacob. And they moved off to the window together, while Evan

spoke to the head waiter about calling them early.

“It is astonishing,” said Jacob, in a gruff voice.

Sandra opened her eyes very slightly. Possibly her nostrils expanded a

little too.

“At half-past six then,” said Evan, coming towards them, looking as if

he faced something in facing his wife and Jacob standing with their

backs to the window.

Sandra smiled at him.

And, as he went to the window and had nothing to say she added, in

broken half-sentences:

“Well, but how lovely—wouldn’t it be? The

Comments (0)