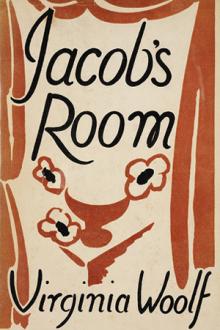

Jacob's Room - Virginia Woolf (polar express read aloud txt) 📗

- Author: Virginia Woolf

- Performer: 0140185704

Book online «Jacob's Room - Virginia Woolf (polar express read aloud txt) 📗». Author Virginia Woolf

engaged in the conduct of daily life is better than the old pageant of

armies drawn out in battle array upon the plain.

“The Height of the season,” said Bonamy.

The sun had already blistered the paint on the backs of the green chairs

in Hyde Park; peeled the bark off the plane trees; and turned the earth

to powder and to smooth yellow pebbles. Hyde Park was circled,

incessantly, by turning wheels.

“The height of the season,” said Bonamy sarcastically.

He was sarcastic because of Clara Durrant; because Jacob had come back

from Greece very brown and lean, with his pockets full of Greek notes,

which he pulled out when the chair man came for pence; because Jacob was

silent.

“He has not said a word to show that he is glad to see me,” thought

Bonamy bitterly.

The motor cars passed incessantly over the bridge of the Serpentine; the

upper classes walked upright, or bent themselves gracefully over the

palings; the lower classes lay with their knees cocked up, flat on their

backs; the sheep grazed on pointed wooden legs; small children ran down

the sloping grass, stretched their arms, and fell.

“Very urbane,” Jacob brought out.

“Urbane” on the lips of Jacob had mysteriously all the shapeliness of a

character which Bonamy thought daily more sublime, devastating, terrific

than ever, though he was still, and perhaps would be for ever, barbaric,

obscure.

What superlatives! What adjectives! How acquit Bonamy of sentimentality

of the grossest sort; of being tossed like a cork on the waves; of

having no steady insight into character; of being unsupported by reason,

and of drawing no comfort whatever from the works of the classics?

“The height of civilization,” said Jacob.

He was fond of using Latin words.

Magnanimity, virtue—such words when Jacob used them in talk with Bonamy

meant that he took control of the situation; that Bonamy would play

round him like an affectionate spaniel; and that (as likely as not) they

would end by rolling on the floor.

“And Greece?” said Bonamy. “The Parthenon and all that?”

“There’s none of this European mysticism,” said Jacob.

“It’s the atmosphere. I suppose,” said Bonamy. “And you went to

Constantinople?”

“Yes,” said Jacob.

Bonamy paused, moved a pebble; then darted in with the rapidity and

certainty of a lizard’s tongue.

“You are in love!” he exclaimed.

Jacob blushed.

The sharpest of knives never cut so deep.

As for responding, or taking the least account of it, Jacob stared

straight ahead of him, fixed, monolithic—oh, very beautiful!—like a

British Admiral, exclaimed Bonamy in a rage, rising from his seat and

walking off; waiting for some sound; none came; too proud to look back;

walking quicker and quicker until he found himself gazing into motor

cars and cursing women. Where was the pretty woman’s face? Clara’s—

Fanny’s—Florinda’s? Who was the pretty little creature?

Not Clara Durrant.

The Aberdeen terrier must be exercised, and as Mr. Bowley was going

that very moment—would like nothing better than a walk—they went

together, Clara and kind little Bowley—Bowley who had rooms in the

Albany, Bowley who wrote letters to the “Times” in a jocular vein about

foreign hotels and the Aurora Borealis—Bowley who liked young people

and walked down Piccadilly with his right arm resting on the boss of his

back.

“Little demon!” cried Clara, and attached Troy to his chain.

Bowley anticipated—hoped for—a confidence. Devoted to her mother,

Clara sometimes felt her a little, well, her mother was so sure of

herself that she could not understand other people being—being—“as

ludicrous as I am,” Clara jerked out (the dog tugging her forwards). And

Bowley thought she looked like a huntress and turned over in his mind

which it should be—some pale virgin with a slip of the moon in her

hair, which was a flight for Bowley.

The colour was in her cheeks. To have spoken outright about her mother—

still, it was only to Mr. Bowley, who loved her, as everybody must; but

to speak was unnatural to her, yet it was awful to feel, as she had done

all day, that she MUST tell some one.

“Wait till we cross the road,” she said to the dog, bending down.

Happily she had recovered by that time.

“She thinks so much about England,” she said. “She is so anxious–”

Bowley was defrauded as usual. Clara never confided in any one.

“Why don’t the young people settle it, eh?” he wanted to ask. “What’s

all this about England?”—a question poor Clara could not have answered,

since, as Mrs. Durrant discussed with Sir Edgar the policy of Sir Edward

Grey, Clara only wondered why the cabinet looked dusty, and Jacob had

never come. Oh, here was Mrs. Cowley Johnson…

And Clara would hand the pretty china teacups, and smile at the

compliment—that no one in London made tea so well as she did.

“We get it at Brocklebank’s,” she said, “in Cursitor Street.”

Ought she not to be grateful? Ought she not to be happy?

Especially since her mother looked so well and enjoyed so much talking

to Sir Edgar about Morocco, Venezuela, or some such place.

“Jacob! Jacob!” thought Clara; and kind Mr. Bowley, who was ever so good

with old ladies, looked; stopped; wondered whether Elizabeth wasn’t too

harsh with her daughter; wondered about Bonamy, Jacob—which young

fellow was it?—and jumped up directly Clara said she must exercise

Troy.

They had reached the site of the old Exhibition. They looked at the

tulips. Stiff and curled, the little rods of waxy smoothness rose from

the earth, nourished yet contained, suffused with scarlet and coral

pink. Each had its shadow; each grew trimly in the diamond-shaped wedge

as the gardener had planned it.

“Barnes never gets them to grow like that,” Clara mused; she sighed.

“You are neglecting your friends,” said Bowley, as some one, going the

other way, lifted his hat. She started; acknowledged Mr. Lionel Parry’s

bow; wasted on him what had sprung for Jacob.

(“Jacob! Jacob!” she thought.)

“But you’ll get run over if I let you go,” she said to the dog.

“England seems all right,” said Mr. Bowley.

The loop of the railing beneath the statue of Achilles was full of

parasols and waistcoats; chains and bangles; of ladies and gentlemen,

lounging elegantly, lightly observant.

“‘This statue was erected by the women of England…’” Clara read out

with a foolish little laugh. “Oh, Mr. Bowley! Oh!” Gallop—gallop—

gallop—a horse galloped past without a rider. The stirrups swung; the

pebbles spurted.

“Oh, stop! Stop it, Mr. Bowley!” she cried, white, trembling, gripping

his arm, utterly unconscious, the tears coming.

“Tut-tut!” said Mr. Bowley in his dressing-room an hour later. “Tut-tut!”—a comment that was profound enough, though inarticulately

expressed, since his valet was handing his shirt studs.

Julia Eliot, too, had seen the horse run away, and had risen from her

seat to watch the end of the incident, which, since she came of a

sporting family, seemed to her slightly ridiculous. Sure enough the

little man came pounding behind with his breeches dusty; looked

thoroughly annoyed; and was being helped to mount by a policeman when

Julia Eliot, with a sardonic smile, turned towards the Marble Arch on

her errand of mercy. It was only to visit a sick old lady who had known

her mother and perhaps the Duke of Wellington; for Julia shared the love

of her sex for the distressed; liked to visit death-beds; threw slippers

at weddings; received confidences by the dozen; knew more pedigrees than

a scholar knows dates, and was one of the kindliest, most generous,

least continent of women.

Yet five minutes after she had passed the statue of Achilles she had the

rapt look of one brushing through crowds on a summer’s afternoon, when

the trees are rustling, the wheels churning yellow, and the tumult of

the present seems like an elegy for past youth and past summers, and

there rose in her mind a curious sadness, as if time and eternity showed

through skirts and waistcoasts, and she saw people passing tragically to

destruction. Yet, Heaven knows, Julia was no fool. A sharper woman at a

bargain did not exist. She was always punctual. The watch on her wrist

gave her twelve minutes and a half in which to reach Bruton Street. Lady

Congreve expected her at five.

The gilt clock at Verrey’s was striking five.

Florinda looked at it with a dull expression, like an animal. She looked

at the clock; looked at the door; looked at the long glass opposite;

disposed her cloak; drew closer to the table, for she was pregnant—no

doubt about it, Mother Stuart said, recommending remedies, consulting

friends; sunk, caught by the heel, as she tripped so lightly over the

surface.

Her tumbler of pinkish sweet stuff was set down by the waiter; and she

sucked, through a straw, her eyes on the looking-glass, on the door, now

soothed by the sweet taste. When Nick Bramham came in it was plain, even

to the young Swiss waiter, that there was a bargain between them. Nick

hitched his clothes together clumsily; ran his fingers through his hair;

sat down, to an ordeal, nervously. She looked at him; and set off

laughing; laughed—laughed—laughed. The young Swiss waiter, standing

with crossed legs by the pillar, laughed too.

The door opened; in came the roar of Regent Street, the roar of traffic,

impersonal, unpitying; and sunshine grained with dirt. The Swiss waiter

must see to the newcomers. Bramham lifted his glass.

“He’s like Jacob,” said Florinda, looking at the newcomer.

“The way he stares.” She stopped laughing.

Jacob, leaning forward, drew a plan of the Parthenon in the dust in

Hyde Park, a network of strokes at least, which may have been the

Parthenon, or again a mathematical diagram. And why was the pebble so

emphatically ground in at the corner? It was not to count his notes that

he took out a wad of papers and read a long flowing letter which Sandra

had written two days ago at Milton Dower House with his book before her

and in her mind the memory of something said or attempted, some moment

in the dark on the road to the Acropolis which (such was her creed)

mattered for ever.

“He is,” she mused, “like that man in Moliere.”

She meant Alceste. She meant that he was severe. She meant that she

could deceive him.

“Or could I not?” she thought, putting the poems of Donne back in the

bookcase. “Jacob,” she went on, going to the window and looking over the

spotted flower-beds across the grass where the piebald cows grazed under

beech trees, “Jacob would be shocked.”

The perambulator was going through the little gate in the railing. She

kissed her hand; directed by the nurse, Jimmy waved his.

“HE’S a small boy,” she said, thinking of Jacob.

And yet—Alceste?

“What a nuisance you are!” Jacob grumbled, stretching out first one leg

and then the other and feeling in each trouser-pocket for his chair

ticket.

“I expect the sheep have eaten it,” he said. “Why do you keep sheep?”

“Sorry to disturb you, sir,” said the ticket-collector, his hand deep in

the enormous pouch of pence.

“Well, I hope they pay you for it,” said Jacob. “There you are. No. You

can stick to it. Go and get drunk.”

He had parted with half-a-crown, tolerantly, compassionately, with

considerable contempt for his species.

Even now poor Fanny Elmer was dealing, as she walked along

Comments (0)