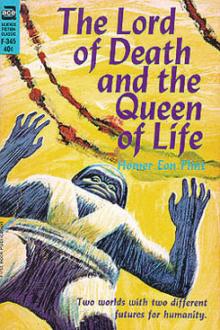

The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life - Homer Eon Flint (online e book reading txt) 📗

- Author: Homer Eon Flint

- Performer: -

Book online «The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life - Homer Eon Flint (online e book reading txt) 📗». Author Homer Eon Flint

“It’s all right,” said the doctor, with an effort. “What you say is true—of most of us.” He added: “Most thinking people realize that when our civilization reaches the point where the getting of a living becomes secondary, instead of primary as at present, a great change is bound to come to the race.”

The Venusian nodded. “Under the conditions which now surround us, you can see, we have vastly more time for what you would call spiritual matters. Only, we label them psychological experiences.

“In fact, the ‘supernatural’ is the Venusian’s daily business!”

There was another pause, during which both Venusians, driving at high speed though they were, once more closed their eyes for a second or so. Estra evidently thought it time to explain.

“For instance, ‘telepathy.’ With us it takes the place of wireless; for we have developed the power to such a point that any Venusian can ‘call up’ any other, no matter where either may be. That is why we need no signs or addresses. There are certain restrictions; for instance, no one can read another’s thoughts without his permission. Of course, we still have speech; speech and language are the ABC’s of the Venusian; and we still keep the telephone, for the sake of checking up now and then. Just now, we are driving for my own house, where there is apparatus which will enable you to both hear and understand an announcement which is shortly to be made.”

There was something decidedly satisfying, especially to Van Emmon, in being taken into the Venusian confidence to this extent. When he put his question, it was with his former aggressiveness much modified. He said:

“I should think that your people have pretty well exhausted the possibilities of the supernatural, by this time. Progress having come to an end, I don’t see what you find to interest you, Myrin.”

“The fact is,” Billie put in, “we feel somewhat disappointed that your people have shown so little interest in us.” And she gave a sidelong glance at Estra, who returned the look with a direct, smiling gaze which sent a flood of color into the architect’s face.

“Look out!” sharply, from Van Emmon; and with barely an inch to spare, Estra steered his car past another which he had nearly overlooked. For another minute or two there was silence; then Myrin said:

“You wonder what there is to interest us. And yet, every time you look up at the stars, the answer is before your eyes.

“You see, although we cannot read your thoughts without your permission, yet you on the earth cannot prevent us from ‘overhearing’ anything that may be said. Under proper conditions, our psychic senses are delicate enough to feel the slightest whisper on the earth.

“That is why Estra and I are able to use your language; we have learned it together with an understanding of your lives and customs, by simply ‘listening in.’ I may add that we are also able to use your eyes; we knew, directly, what you people looked like before you arrived.

“Well, it is our ambition to visit, in spirit, every planet in the universe!

“There are hundreds of millions of stars; every one is a sun; and each has planets. One in a hundred contains life; some very elementary, others much more advanced than we are.

“So far, we have been able to study nearly two thousand worlds besides those in this solar system. Do you still think, friend, we have nothing to interest us?”

She raised a hand in a gesture of emphasis; and it was then that Billie, her eyes on Myrin’s fingers, saw another sign of the great advancement these people had made—direct proof, in fact, of what Myrin had just claimed.

For there must have been a tremendous gain in the intellect to have caused such a drain upon the body as Billie saw. In no other way could it be explained; the minds of the Venusians had grown at a fearful cost to flesh and blood.

Not only were the fingernails entirely lacking from Myrin’s hand, but the lower joints of her four fingers, from the palm to the knuckles were grown smoothly together.

XII THE MENTAL LIMIT“Make yourselves at home,” said Estra, as they stepped into his apartment. The cars just filled his balcony. “This is my ‘workshop’; see if you can guess my occupation, from what you see. As for Myrin and myself, we must make certain preparations before the announcement is made.”

They disappeared, and the four inspected the place. As in the other house they had entered, the room was provided with a double row of small windows; some being down near the floor and the others level with the eyes. These, in addition to two doors, all of which were of translucent material.

On low benches about the room were a number of instruments, some of which looked familiar to the doctor. He said he had seen something much like them in psychology class, during his college days. For the most part, their appearance defied ordinary description. [Footnote: Physicians, biologists, and others interested in matters of this nature will find the above fully treated in Dr. Kinney’s reports to the A. M. A.]

But one piece of apparatus was given such prominence that it is worth detailing. It consisted of a hollow, cube-shaped metal framework; about a foot in either direction, upon which was mounted about forty long thumb-screws, all pointing toward the inside of the frame. The inner ends of the screws were provided with small silver pads; while the outer ends were so connected, each with a tiny dial, as to register the amount of motion of the screw. Smith turned one of them in and out, and said it reminded him of a micrometer gage.

Then Billie noted that the entire device was so placed upon the bench as to set directly over a hole, about ten inches in diameter. And under the bench was one of the saddlelike chairs. The architect’s antiquarian lore came back to her with a rush, and she remembered something she had seen in a museum—a relic of the inquisition.

“Good Heavens!” she whispered. “What is this—an instrument of torture?”

It certainly looked mightily like one of the head-crushing devices Billie had seen. Thumb-screws and all, this appeared to be only a very elaborate “persuader,” for use upon those who must be made to talk.

But the doctor was thinking hard. A big light flashed into his eyes. “This,” he declared, positively, “is something that will become a matter of course in our own educational system, as soon as the science of phrenology is better understood.” And next second he had ducked under the bench, and thrust his head through the round hole, so that his skull was brought into contact with some of those padded thumb-screws.

“Get the idea?” he finished. “It’s a cranium-meter!”

It did not take Smith long to reach the next conclusion. “Then,” said he, “our friend Estra is connected with their school system. Can’t say what he would be called, but I should say his function is to measure the capacity of students for various kinds of knowledge, in order that their education may be adapted accordingly.

“Might call him a brain-surveyor,” he concluded.

“Or a noodle-smith,” added the geologist, deprecatingly.

“Rather, a career-appraiser!” indignantly, from Billie. “People look to him to suggest what they should take up, and what they should leave alone. Why, he’s one of the most important men on this whole planet!”

And again the doctor was a witness to a clash of eyes between the girl and the geologist. Van Emmon said nothing further, however, but turned to examine an immense bookcase on the other side of the room.

This case had shelves scarcely two inches apart, and about half as deep, and held perhaps half a million extremely small books. Each comprised many hundreds of pages, made of a perfectly opaque, bluish-white material of such incredible thinness that ordinary India-paper resembled cardboard by comparison.

They were printed much the same as any other book, except that the characters were of microscopic size, and the lines extremely close together. Also, in some of the books these lines were black and red, alternating.

Billie eagerly examined one of the diminutive volumes under a strong glass, and pronounced the black-printed characters not unlike ancient Gothic type. She guessed that the language was synthetic, like Roman or Esperanto, and that the alphabet numbered sixty or seventy.

“The red lines,” she added, not so confidently, “are in a different language. Looks wonderfully like Persian.” By this time the others were doing the same as she, and marveling to note that, wherever the red and black lines were employed, invariably the black were in the same language; while the red characters were totally different in each book.

Suddenly Smith gave a start, so vigorously that the other turned in alarm. He was holding one of the books as though it were white hot. “Look!” he stuttered excitedly. “Just look at it!”

And no wonder. In the book he had chanced to pick up, the red lines were printed in ENGLISH.

“Talk about your finds!” exclaimed Billie, in an awe-struck tone. “Why, this library is a literal translation of the languages of—” she fairly gasped as she recalled Myrin’s words—“thousands of planets!”

After that she fell silent. Plainly the discovery had profoundly affected and strengthened her notion of remaining on the planet. Van Emmon, watching her narrowly, saw her give the room an appraising glance which meant, plain as day, “I’d like to keep this place in spick and span condition!” And another, not so easy to interpret: “I’d like to show these people a thing or two about designing houses!” And the geologist’s heart sank for an instant.

He turned resolutely to the bookcase, and shortly found something which he showed to the doctor. It was a book printed all in “Venusian.” They carefully translated the title-page, using one of the interlinear English books as a guide; and saw that it was a complete text-book on astral development.

“With these instructions,” the doctor declared, “any one could do as the Venusians do—visit other worlds in spirit!”

Just then Estra and Myrin returned. They were moving at what was, for them, a rapid pace; and to all appearances they were rather excited.

“We were not able to make these records as perfect as we would like,” said Estra, holding up four disks similar to the ones which still lay in the explorers’ translating machines. He proceeded to open the little black cases and make the exchange. “There will be words used which I did not see fit to incorporate in the original vocabulary, but which you will have to understand perfectly if this announcement is to mean anything to you.”

“Thank you,” said the doctor quietly. “And now, don’t you think we had best know in advance, just what is to be the subject of—”

“Hush!” whispered Estra; and next second they were listening to the telephone in amazement.

XIII THE WAR OF THE SEXES“In accordance with my promise,” stated a high-pitched effeminate voice, “I am going to demonstrate a juvenation method upon which I have worked for the past one hundred and twenty-two years.”

There was a brief pause, during which Estra hurriedly explained that the man who was making the speech was located far on the other side of the planet, in a hall like the one the four had first visited; and that he was making the demonstration before a great gathering of scientists. “Too bad you cannot see as we do,” commented the Venusian. “However, Savarona may go into the

Comments (0)