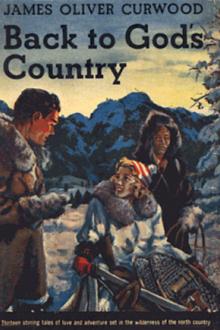

Back to God's Country and Other Stories - James Oliver Curwood (summer reads .txt) 📗

- Author: James Oliver Curwood

- Performer: -

Book online «Back to God's Country and Other Stories - James Oliver Curwood (summer reads .txt) 📗». Author James Oliver Curwood

In the second year, with the beginning of trapping, fell the second and third great events. Cummins disappeared. Then came the Englishman. For a time the first of these two overshadowed everything else at the post. Cummins had gone to prospect a new trap-line, and was to sleep out the first night. The second night he was still gone. On the third day came the “Beeg Snow.” It began at dawn, thickened as the day went, and continued to thicken until it became that soft, silent deluge of white in which no man dared venture a thousand yards from his door. The Aurora was hidden. There were no stars in the sky at night. Day was weighted with a strange, noiseless gloom. In all that wilderness there was not a creature that moved. Sixty hours later, when visible life was resumed again, the caribou, the wolf and the fox dug themselves up out of six feet of snow, and found the world changed.

It was at the beginning of the “Beeg Snow” that Jan went to the woman’s cabin. He tapped upon her door with the timidity of a child, and when she opened it, her great eyes glowing at him in wild questioning, her face white with a terrible fear, there was a chill at his heart which choked back what he had come to say. He walked in dumbly and stood with the snow falling off him in piles, and when Cummins’ wife saw neither hope nor foreboding in his dark, set face she buried her face in her arms upon the little table and sobbed softly in her despair. Jan strove to speak, but the Cree in him drove back what was French and “just white,” and he stood in mute, trembling torture. “Ah, the Great God!” his soul was crying. “What can I do?”

Upon its little cot the woman’s child was asleep. Beside the stove there were a few sticks of wood. He stretched himself until his neck creaked to see if there was water in the barrel near the door. Then he looked again at the bowed head and the shivering form at the table. In that moment Jan’s resolution soared very near to the terrible.

“Mees Cummin, I go hunt for heem!” he cried. “I go hunt for heem—an’ fin’ heem!”

He waited another moment, and then backed softly toward the door.

“I hunt for heem!” he repeated, fearing that she had not heard.

She lifted her face, and the beating of Jan’s heart sounded to him like the distant thrumming of partridge wings. Ah, the Great God—would he ever forget that look! She was coming to him, a new glory in her eyes, her arms reaching out, her lips parted! Jan knew how the Great Spirit had once appeared to Mukee, the half-Cree, and how a white mist, like a snow veil, had come between the halfbreed’s eyes and the wondrous thing he beheld. And that same snow veil drifted between Jan and the woman. Like in a vision he saw her glorious face so near to him that his blood was frightened into a strange, wonderful sensation that it had never known before. He felt the touch of her sweet breath, he heard her passionate prayer, he knew that one of his rough hands was clasped in both her own—and he knew, too, that their soft, thrilling warmth would remain with him until he died, and still go into Paradise with him.

When he trudged back into the snow, knee-deep now, he sought Mukee, the halfbreed. Mukee had suffered a lynx bite that went deep into the bone, and Cummins’ wife had saved his hand. After that the savage in him was enslaved to her like an invisible spirit, and when Jan slipped on his snowshoes to set out into the deadly chaos of the “Beeg Storm” Mukee was ready to follow. A trail through the spruce forest led them to the lake across which Jan knew that Cummins had intended to go. Beyond that, a matter of six miles or so, there was a deep and lonely break between two mountainous ridges in which Cummins believed he might find lynx. Indian instinct guided the two across the lake. There they separated, Jan going as nearly as he could guess into the northwest, Mukee trailing swiftly and hopelessly into the south, both inspired in the face of death by the thought of a woman with sunny hair, and with lips and eyes that had sent many a shaft of hope and gladness into their desolate hearts.

It was no great sacrifice for Jan, this struggle with the “Beeg Snows” for the woman’s sake. What it was to Mukee, the half-Cree, no man ever guessed or knew, for it was not until the late spring snows had gone that they found what the foxes and the wolves had left of him, far to the south.

A hand, soft and gentle, guided Jan. He felt the warmth of it and the thrill of it, and neither the warmth nor the thrill grew less as the hours passed and the snow fell deeper. His soul was burning with a joy that it had never known. Beautiful visions danced in his brain, and always he heard the woman’s voice praying to him in the little cabin, saw her eyes upon him through that white snow veil! Ah, what would he not give if he could find the man, if he could take Cummins back to his wife, and stand for one moment more with her hands clasping his, her joy flooding him with a sweetness that would last for all time! He plunged fearlessly into the white world beyond the lake, his wide snowshoes sinking ankle-deep at every step. There was neither rock nor tree to guide him, for everywhere was the heavy ghost-raiment of the Indian God. The balsams were bending under it, the spruces were breaking into hunchback forms, the whole world was twisted in noiseless torture under its increasing weight, and out through the still terror of it all Jan’s voice went in wild echoing shouts. Now and then he fired his rifle, and always he listened long and intently. The echoes came back to him, laughing, taunting, and then each time fell the mirthless silence of the storm. Night came, a little darker than the day, and Jan stopped to build a fire and eat sparingly of his food, and to sleep. It was still night when he aroused himself and stumbled on. Never did he take the weight of his rifle from his right hand or shoulder, for he knew this weight would shorten the distance traveled at each step by his right foot, and would make him go in a circle that would bring him back to the lake. But it was a long circle. The day passed. A second night fell upon him, and his hope of finding Cummins was gone. A chill crept in where his heart had been so warm, and somehow that soft pressure of a woman’s hand upon his seemed to become less and less real to him. The woman’s prayers were following him, her heart was throbbing with its hope in him—and he had failed! On the third day, when the storm was over, Jan staggered hopelessly into the post. He went straight to the woman, disgraced, heartbroken. When he came out of the little cabin he seemed to have gone mad. A wondrously strange thing had happened. He had spoken not a word, but his failure and his sufferings were written in his face, and when Cummins’ wife saw and understood she went as white as the underside of a poplar leaf in a clouded sun. But that was not all. She came to him, and clasped one of his half-frozen hands to her bosom, and he heard her say, “God bless you forever, Jan! You have done the best you could!” The Great God—was that not reward for the risking of a miserable, worthless life such as his? He went to his shack and slept long, and dreamed, sometimes of the woman, and of Cummins and Mukee, the half-Cree.

On the first crust of the new snow came the Englishman up from Fort Churchill, on Hudson’s Bay. He came behind six dogs, and was driven by an Indian, and he bore letters to the factor which proclaimed him something of considerable importance at the home office of the Company, in London. As such he was given the best bed in the factor’s rude home. On the second day he saw Cummins’ wife at the Company’s store, and very soon learned the history of Cummins’ disappearance.

That was the beginning of the real tragedy at the post. The wilderness is a grim oppressor of life. To those who survive in it the going out of life is but an incident, an irresistible and natural thing, unpleasant but without horror. So it was with the passing of Cummins. But the Englishman brought with him something new, as the woman had brought something new, only in this instance it was an element of life which Jan and his people could not understand, an element which had never found a place, and never could, in the hearts and souls of the post. On the other hand, it promised to be but an incident to the Englishman, a passing adventure in pleasure common to the high and glorious civilization from which he had come. Here again was that difference of viewpoint, the eternity of difference between the middle and the end of the earth. As the days passed, and the crust grew deeper upon the “Beeg Snows,” the tragedy progressed rapidly toward finality. At first Jan did not understand. The others did not understand. When the worm of the Englishman’s sin revealed itself it struck them with a dumb, terrible fear.

The Englishman came from among women. For months he had been in a torment of desolation. Cummins’ wife was to him like a flower suddenly come to relieve the tantalizing barrenness of a desert, and with the wiles and soft speech of his kind he sought to breathe its fragrance. In the weeks that followed the flower seemed to come nearer to him, and this was because Jan and his people had not as yet fully measured the heart of the woman, and because the Englishman had not measured Jan and his people he talked a great deal when enthused by the warmth of the box stove and his thoughts. So human passions were set at play. Because the woman knew nothing of what was said about the box stove she continued in the even course of her pure life, neither resisting nor encouraging the newcomer, yet ever tempting him with that sweetness which she gave to all alike, and still praying in the still hours of night that Cummins would return to her. As yet there was no suspicion in her soul. She accepted the Englishman’s friendship. His sympathy for her won him a place in her recognition of things good and true. She did not hear the false note, she saw no step that promised evil. Only Jan and his people saw and understood the one-sided struggle, and shivered at the monstrous evil of it. At least they thought they saw and understood, which was enough. Like so many faithful beasts they were ready to spring, to rend flesh, to tear life out of him who threatened the desecration of all that was good and pure and beautiful to them, and yet, dumb in their devotion and faith, they waited and watched for a sign from the woman. The blue eyes of

Comments (0)