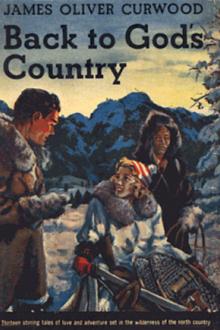

Back to God's Country and Other Stories - James Oliver Curwood (summer reads .txt) 📗

- Author: James Oliver Curwood

- Performer: -

Book online «Back to God's Country and Other Stories - James Oliver Curwood (summer reads .txt) 📗». Author James Oliver Curwood

“As you shall see, this other man was a beast. On the day preceding the night of the terrible storm, the woman’s husband set out for the settlement to bring back supplies. Hardly had he gone, when the beast came to the cabin. He found himself alone with the woman.

“A mile from his cabin, the husband stopped to light his pipe. See, gentlemen, how the Supreme Arbiter played His hand. The man attempted to unscrew the stem, and the stem broke. In the wilderness you must smoke. Smoke is your company. It is voice and companionship to you. There were other pipes at the settlement, ten miles away; but there was also another pipe at the cabin, one mile away. So the husband turned back. He came up quietly to his door, thinking that he would surprise his wife. He heard voices—a man’s voice, a woman’s cries. He opened the door, and in the excitement of what was happening within neither the man nor the woman saw nor heard him. They were struggling. The woman was in the man’s arms, her hair torn down, her small hands beating him in the face, her breath coming in low, terrified cries. Even as the husband stood there for the fraction of a second, taking in the terrible scene, the other man caught the woman’s face to him, and kissed her. And then—it happened.

“It was a terrible fight; and when it was over the beast lay on the floor, bleeding and dead. Gentlemen, the Supreme Arbiter BROKE A PIPE-STEM, and sent the husband back in time!”

No one spoke as Father Charles drew his coat still closer about him. Above the tumult of the storm another sound came to them—the distant, piercing shriek of a whistle.

“The husband dug a grave through the snow and in the frozen earth,” concluded Father Charles; “and late that afternoon they packed up a bundle and set out together for the settlement. The storm overtook them. They had dropped for the last time into the snow, about to die in each other’s arms, when I put my light in the window. That is all; except that I knew them for several years afterward, and that the old happiness returned to them—and more, for the child was born, a miniature of its mother. Then they moved to another part of the wilderness, and I to still another. So you see, gentlemen, what a snow-bound train may mean, for if an old sea tale, a broken pipe-stem—”

The door at the end of the smoking-room opened suddenly. Through it there came a cold blast of the storm, a cloud of snow, and a man. He was bundled in a great bearskin coat, and as he shook out its folds his strong, ruddy face smiled cheerfully at those whom he had interrupted.

Then, suddenly, there came a change in his face. The merriment went from it. He stared at Father Charles. The priest was rising, his face more tense and whiter still, his hands reaching out to the stranger.

In another moment the stranger had leaped to him—not to shake his hands, but to clasp the priest in his great arms, shaking him, and crying out a strange joy, while for the first time that night the pale face of Father Charles was lighted up with a red and joyous glow.

After several minutes the newcomer released Father Charles, and turned to the others with a great hearty laugh.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “you must pardon me for interrupting you like this. You will understand when I tell you that Father Charles is an old friend of mine, the dearest friend I have on earth, and that I haven’t seen him for years. I was his first penitent!”

PETER GODPeter God was a trapper. He set his deadfalls and fox-baits along the edge of that long, slim finger of the Great Barren, which reaches out of the East well into the country of the Great Bear, far to the West. The door of his sapling-built cabin opened to the dark and chilling gray of the Arctic Circle; through its one window he could watch the sputter and play of the Northern Lights; and the curious hissing purr of the Aurora had grown to be a monotone in his ears.

Whence Peter God had come, and how it was that he bore the strange name by which he went, no man had asked, for curiosity belongs to the white man, and the nearest white men were up at Fort MacPherson, a hundred or so miles away.

Six or seven years ago Peter God had come to the post for the first time with his furs. He had given his name as Peter God, and the Company had not questioned it, or wondered. Stranger names than Peter’s were a part of the Northland; stranger faces than his came in out of the white wilderness trails; but none was more silent, or came in and went more quickly. In the gray of the afternoon he drove in with his dogs and his furs; night would see him on his way back to the Barrens, supplies for another three months of loneliness on his sledge.

It would have been hard to judge his age—had one taken the trouble to try. Perhaps he was thirty-eight. He surely was not French. There was no Indian blood in him. His heavy beard was reddish, his long thick hair distinctly blond, and his eyes were a bluish-gray.

For seven years, season after season, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s clerk had written items something like the following in his record-books:

Feb. 17. Peter God came in to-day with his furs. He leaves this afternoon or tonight for his trapping grounds with fresh supplies.

The year before, in a momentary fit of curiosity, the clerk had added:

Curious why Peter God never stays in Fort MacPherson overnight.

And more curious than this was the fact that Peter God never asked for mail, and no letter ever came to Fort MacPherson for him.

The Great Barren enveloped him and his mystery. The yapping foxes knew more of him than men. They knew him for a hundred miles up and down that white finger of desolation; they knew the peril of his baits and his deadfalls; they snarled and barked their hatred and defiance at the glow of his lights on dark nights; they watched for him, sniffed for signs of him, and walked into his clever deathpits.

The foxes and Peter God! That was what this white world was made up of—foxes and Peter God. It was a world of strife between them. Peter God was killing—but the foxes were winning. Slowly but surely they were breaking him down—they and the terrible loneliness. Loneliness Peter God might have stood for many more years. But the foxes were driving him mad. More and more he had come to dread their yapping at night. That was the deadly combination—night and the yapping. In the day-time he laughed at himself for his fears; nights he sweated, and sometimes wanted to scream. What manner of man Peter God was or might have been, and of the strangeness of the life that was lived in the maddening loneliness of that mystery-cabin in the edge of the Barren, only one other man knew.

That was Philip Curtis.

Two thousand miles south, Philip Curtis sat at a small table in a brilliantly lighted and fashionable cafe. It was early June, and Philip had been down from the North scarcely a month, the deep tan was still in his face, and tiny wind and snow lines crinkled at the corners of his eyes. He exuded the life of the big outdoors as he sat opposite pallid-cheeked and weak-chested Barrow, the Mica King, who would have given his millions to possess the red blood in the other’s veins.

Philip had made his “strike,” away up on the Mackenzie. That day he had sold out to Barrow for a hundred thousand. Tonight he was filled with the flush of joy and triumph.

Barrow’s eyes shone with a new sort of enthusiasm as he listened to this man’s story of grim and fighting determination that had led to the discovery of that mountain of mica away up on the Clearwater Bulge. He looked upon the other’s strength, his bronzed face and the glory of achievement in his eyes, and a great and yearning hopelessness burned like a dull fire in his heart. He was no older than the man who sat on the other side of the table—perhaps thirty-five; yet what a vast gulf lay between them! He with his millions; the other with that flood of red blood coming and going in his body, and his wonderful fortune of a hundred thousand! Barrow leaned a little over the table, and laughed. It was the laugh of a man who had grown tired of life, in spite of his millions. Day before yesterday a famous specialist had warned him that the threads of his life were giving way, one by one. He told this to Curtis. He confessed to him, with that strange glow in his eyes,—a glow that was like making a last fight against total extinguishment,—that he would give up his millions and all he had won for the other’s health and the mountain of mica.

“And if it came to a close bargain,” he said, “I wouldn’t hold out for the mountain. I’m ready to quit—and it’s too late.”

Which, after a little, brought Philip Curtis to tell so much as he knew of the story of Peter God. Philip’s voice was tuned with the winds and the forests. It rose above the low and monotonous hum about them. People at the two or three adjoining tables might have heard his story, if they had listened. Within the immaculateness of his evening dress, Barrows shivered, fearing that Curtis’ voice might attract undue attention to them. But other people were absorbed in themselves. Philip went on with his story, and at last, so clearly that it reached easily to the other tables, he spoke the name of Peter God.

Then came the interruption, and with that interruption a strange and sudden upheaval in the life of Philip Curtis that was to mean more to him than the discovery of the mica mountain. His eyes swept over Barrow’s shoulder, and there he saw a woman. She was standing. A low, stifled cry had broken from her almost simultaneously with his first glimpse of her, and as he looked, Philip saw her lips form gaspingly the name he had spoken—Peter God!

She was so near that Barrow could have turned and touched her. Her eyes were like luminous fires as she stared at Philip. Her face was strangely pale. He could see her quiver, and catch her breath. And she was looking at him. For that one moment she had forgotten the presence of others.

Then a hand touched her arm. It was the hand of her elderly escort, in whose face were anxiety and wonder. The woman started and took her eyes from Philip. With her escort she seated herself at a table a few paces away, and for a few moments Philip could see she was fighting for composure, and that it cost her a struggle to keep her eyes from turning in his direction while she talked in a low voice to her companion.

Philip’s heart was pounding like an engine. He knew that she was talking about him now, and he knew that she had cried out when he had spoken Peter God’s name. He forgot Barrow as he looked at her. She was exquisite, even with that gray pallor that had come so suddenly into her cheeks. She was not young, as the age of youth is measured.

Comments (0)