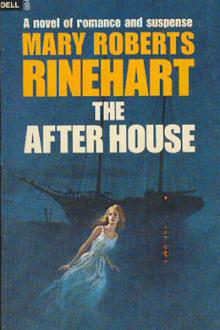

The After House - Mary Roberts Rinehart (new books to read .TXT) 📗

- Author: Mary Roberts Rinehart

- Performer: -

Book online «The After House - Mary Roberts Rinehart (new books to read .TXT) 📗». Author Mary Roberts Rinehart

Tuner was violent that day. I found all four women awake and dressed, and Mrs. Turner, whose hour it was on duty, in a chair outside the door. The stewardess, her arm in a sling, was making tea over a spirit-lamp, and Elsa was helping her. Mrs. Johns was stretched on a divan, and on the table lay a small revolver.

Clearly, Elsa had told the incident of the key. I felt at once the atmosphere of antagonism. Mrs. Johns watched me coolly from under lowered eyelids. The stewardess openly scowled. And Mrs. Turner rose hastily, and glanced at Mrs. Johns, as if in doubt. Elsa had her back to me, and was busy with the cups.

“I’m afraid you’ve had a bad night,” I said.

“A very bad night,” Mrs. Turner replied stiffly.

“Delirium?”

“Very marked. He has talked of a white figure - we cannot quite make it out. It seems to be Wilmer - Mr. Vail.”

She had not opened the door, but stood, nervously twisting her fingers, before it.

“The bromides had no effect?”

She glanced helplessly at the others. “None,” she said, after a moment.

Elsa Lee wheeled suddenly and glanced scornfully at her sister.

“Why don’t you tell him?” she demanded. “Why don’t you say you didn’t give the bromides?”

“Why not?”

Mrs. Johns raised herself on her elbow and looked at me.

“Why should we?” she asked. “How do we know what you are giving him? You are not friendly to him or to us. We know what you are trying to do - you are trying to save yourself, at any cost. You put a guard at the companionway. You rail off the deck for our safety. You drop the storeroom key in Mr. Turner’s cabin, where Elsa will find it, and will be obliged to acknowledge she found it, and then take it from her by force, so you can show it later on and save yourself!”

Elsa turned on her quickly.

“I told you how he got it, Adele. I tried to throw it -”

“Oh, if you intend to protect him!”

“I am rather bewildered,” I said slowly; “but, under the circumstances, I suppose you do not wish me to look after Mr. Turner?”

“We think not” - from Mrs. Turner.

“How will you manage alone?”

Mrs. Johns got up and lounged to the table. She wore a long satin negligee of some sort, draped with lace. It lay around her on the floor in gleaming lines of soft beauty. Her reddish hair was low on her neck, and she held a cigarette, negligently, in her teeth. All the women smoked, Mrs. Johns incessantly.

She laid one hand lightly on the revolver, and flicked the ash from her cigarette with the other.

“We have decided,” she said insolently, “that, if the crew may establish a deadline, so may we. Our deadline is the foot of the companionway. One of us will be on watch always. I am an excellent shot.”

“I do not doubt it.” I faced her. “I am afraid you will suffer for air; otherwise, the arrangement is good. You relieve me of part of the responsibility for your safety. Tom will bring your food to the steps and leave it there.”

“Thank you.”

“With good luck, two weeks will see us in port; and then -”

“In port! You are taking us back?”

“Why not?”

She picked up the revolver and examined it absently. Then she glanced at me, and shrugged her shoulders. “How can we know? Perhaps this is a mutiny, and you are on your way to some God forsaken island. That’s the usual thing among pirates, isn’t it?”

“I have no answer to that, Mrs. Johns,” I said quietly, and turned to where Elsa sat.

“I shall not come back unless you send for me,” I said. “But I want you to know that my one object in life from now on is to get you back safely to land; that your safety comes first, and that the vigilance on deck in your interest will not be relaxed.”

“Fine words!” the stewardess muttered.

The low mumbling from Turner’s room had persisted steadily. Now it rose again in the sharp frenzy that had characterized it through the long night.

“Don’t look at me like that, man!” he cried, and then “He’s lost a hand! A hand!”

Mrs. Turner went quickly into the cabin, and the sounds ceased. I looked at Elsa, but she avoided my eyes. I turned heavily and went up the companionway.

It rained heavily all that day. Late in the afternoon we got some wind, and all hands turned out to trim sail. Action was a relief, and the weather suited our disheartened state better than had the pitiless August sun, the glaring white of deck and canvas, and the heat.

The heavy drops splashed and broke on top of the jollyboat, and, as the wind came up, it rode behind us like a live thing.

Our distress signal hung sodden, too wet to give more than a dejected response to the wind that tugged at it. Late in the afternoon we sighted a large steamer, and when, as darkness came on, she showed no indication of changing her course, Burns and I sent up a rocket and blew the fog horn steadily. She altered her course then and came towards us, and we ran up our code flags for immediate assistance; but she veered off shortly after, and went on her way. We made no further effort to attract her attention. Burns thought her a passenger steamer for the Bermudas, and, as her way was not ours, she could not have been of much assistance.

One or two of the men were already showing signs of strain. Oleson, the Swede, developed a chill, followed by fever and a mild delirium, and Adams complained of sore throat and nausea. Oleson’s illness was genuine enough. Adams I suspected of malingering. He had told the men he would not go up to the crow’s-nest again without a revolver, and this I would not permit.

Our original crew had numbered nine - with the cook and Williams, eleven. But the two Negroes were not seamen, and were frightened into a state bordering on collapse. Of the men actually useful, there were left only five: Clarke, McNamara, Charlie Jones, Burns, and myself; and I was a negligible quantity as regarded the working of the ship.

With Burns and myself on guard duty, the burden fell on Clarke, McNamara, and Jones. A suggestion of mine that we release Singleton was instantly vetoed by the men. It was arranged, finally, that Clarke and McNamara take alternate watches at the wheel, and Jones be given the lookout for the night, to be relieved by either Burns or myself.

I watched the weather anxiously. We were too short-handed to manage any sort of a gale; and yet, the urgency of our return made it unwise to shorten canvas too much. It was as well, perhaps, that I had so much to distract my mind from the situation in the after house.

The second of the series of curious incidents that complicated our return voyage occurred that night. I was on watch from eight bells midnight until four in the morning. Jones was in the crow’s-nest, McNamara at the wheel. I was at the starboard forward corner of the after house, looking over the rail. I thought that I had seen the lights of a steamer.

The rain had ceased, but the night was still very dark. I heard a sort of rapping from the forward house, and took a step toward it, listening. Jones heard it, too, and called down to me, nervously, to see what was wrong.

I called up to him, cautiously, to come dawn and take my place while I investigated. I thought it was Singleton. When Jones had taken up his position at the companionway, I went forward. The knocking continued, and I traced it to Singleton’s cabin. His window was open, being too small for danger, but barred across with strips of wood outside, like those in the after house. But he was at the door, hammering frantically. I called to him through the open window, but the only answer was renewed and louder pounding.

I ran around to his door, and felt for the key, which I carried.

“What is the matter?” I called.

“Who is it?”

“Leslie.”

“For God’s sake, open the door!”

I unlocked it and threw it open. He retreated before me, with his hands out, and huddled against the wall beside the window. I struck a match. His face was drawn and distorted, and he held his arm up as if to ward off a blow.

I lighted the lamp, for there were no electric lights in the forward house, and stared at him, amazed. Satisfied that I was really Leslie, he had stooped, and was fumbling under the window. When he straightened, he held something out to me in the palm of his shaking hand. I saw, with surprise, that it was a tobacco-pouch.

“Well?” I demanded.

“It was on the ledge,” he said hoarsely. “I put it there myself. All the time I was pounding, I kept saying that, if it was still there, it was not true - I’d just fancied it. If the pouch was on the floor, I’d know.”

“Know what?”

“It was there,” he said, looking over his shoulder. “It’s been there three times, looking in - all in white, and grinning at me.”

“A man?”

“It - it hasn’t got any face.”

“How could it grin - at you if it has n’t any face?” I demanded impatiently. “Pull yourself together and tell me what you saw.”

It was some time before he could tell a connected story, and, when he did, I was inclined to suspect that he had heard us talking the night before, had heard Adams’s description of the intruder on the forecastle-head, and that, what with drink and terror, he had fancied the rest. And yet, I was not so sure.

“I was asleep, the first time,” he said. “I don’t know how long ago it was. I woke up cold, with the feeling that something was looking at me. I raised up in bed, and there was a thing at the window. It was looking in.”

“What sort of a thing?”

“What I told you - white.”

“A white head?”

“It wasn’t a head. For God’s sake, Leslie! I can’t tell you any more than that. I saw it. That’s enough. I saw it three times.”

“It isn’t enough for me,” I said doggedly. “It hadn’t any head or face, but it looked in! It’s dark out there. How could you see?”

For reply, he leaned over and, turning down the lamp, blew it out. We sat in the smoking darkness, and slowly, out of the thick night, the window outlined itself. I could see it distinctly. But how, white and faceless, had it stared in at the window, or reached through the bars, as Singleton declared it had done, and waved a fingerless hand at us?

He was in a state of mental and physical collapse, and begged so pitifully not to be left, that at last I told him I would take him with me, on his promise to remain in a chair until dawn, and to go back without demur. He sat near me, amidships, huddled down among the cushions of one of the wicker chairs, not sleeping, but staring straight out, motionless.

With the first light of dawn Burns relieved me, and I went forward with Singleton. He dropped into his bunk,

Comments (0)