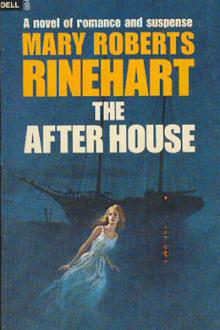

The After House - Mary Roberts Rinehart (new books to read .TXT) 📗

- Author: Mary Roberts Rinehart

- Performer: -

Book online «The After House - Mary Roberts Rinehart (new books to read .TXT) 📗». Author Mary Roberts Rinehart

“Have you been ill again?” she asked.

I put my hand to my chin. “Not ill,” I said; “merely unshaven.”

“But you are pale, and your eyes are sunk in your head.”

“We are very short-handed and - no one has slept much.”

“Or eaten at all, I imagine,” she said. “When do we get in?”

“I can hardly say. With this wind, perhaps Tuesday.”

“Where?”

“Philadelphia.”

“You intend to turn the yacht over to the police?”

“Yes, Miss Lee.”

“Every one on it?”

“That is up to the police. They will probably not hold the women. You will be released, I imagine, on your own recognizance.”

“And - Mr. Turner?”

“He will have to take his luck with the rest of us.”

She asked me no further questions, but switched at once to what had brought her on deck.

“The cabin is unbearable,” she said. “We are willing to take the risk of opening the after companion door.”

But I could not allow this, and I tried to explain my reasons. The crew were quartered there, for one; for the other, whether they were willing to take the risk or not, I would not open it without placing a guard there, and we had no one to spare for the duty. I suggested that they use the part of the deck reserved for them, where it was fairly cool under the awning; and, after a dispute below, they agreed to this. Turner, very weak, came up the few steps slowly, but refused my proffered help. A little later, he called me from the rail and offered me a cigar. The change in him was startling.

We took advantage of their being on deck to open the windows and air the after house. But all were securely locked and barred before they went below again. It was the first time they had all been on deck together since the night of the 11th. It was a different crowd of people that sat there, looking over the rail and speaking in monosyllables: no bridge, no glasses clinking with ice, no elaborate toilets and carefully dressed hair, no flash of jewels, no light laughter following one of poor Vail’s sallies.

At ten o’clock they went below, but not until I had quietly located every member of the crew. I had the watch from eight to twelve that night, and at half after ten Mrs. Johns came on deck again. She did not speak to me, but dropped into a steamer-chair and yawned, stretching out her arms. By the light of the companion lantern, I saw that she had put on one of the loose negligees she affected for undress, and her arms were bare except for a fall of lace.

At eight bells (midnight) Burns took my place. Charlie Jones was at the wheel, and McNamara in the crow’s-nest. Mrs. Johns was dozing in her chair. The yacht was making perhaps four knots, and, far behind, the small white light of the jollyboat showed where she rode.

I slept heavily, and at eight bells I rolled off my blanket and prepared to relieve Burns. I was stiff, weary, unrefreshed. The air was very still and we were hardly moving. I took a pail of water that stood near the rail, and, leaning far out, poured it over my head and shoulders. As I turned, dripping, Jones, relieved of the wheel, touched me on the arm.

“Go back to sleep, boy,” he said kindly. “We need you, and we’re goin’ to need you more when we get ashore. You’ve been talkin’ in your sleep till you plumb scared me.”

But I was wide awake by that time, and he had had as little sleep as I had. I refused, and we went forward together, Jones to get coffee, which stood all night on the galley stove.

It was still dark. The dawn, even in the less than four weeks we had been out, came perceptibly later. At the port forward corner of the after house, Jones stumbled over something, and gave a sharp exclamation. The next moment he was on his knees, lighting a match.

Burns lay there on his face, unconscious, and bleeding profusely from a cut on the back of his head - but not dead.

My first thought was of the after house. Jones, who had been fond of Burns, was working over him, muttering to himself. I felt his heart, which was beating slowly but regularly, and, convinced that he was not dying, ran down into the after house. The cabin was empty: evidently the guard around the pearl handled revolver had been given up on the false promise of peace. All the lights were going, however, and the heat was suffocating.

I ran to Miss Lee’s door, and tried it. It was locked, but almost instantly she spoke from inside:

“What is it?”

“Nothing much. Can you come out?”

She came a moment later, and I asked her to call into each cabin to see if every one was safe. The result was reassuring - no one had been disturbed; and I was put to it to account to Miss Lee for my anxiety without telling her what had happened. I made some sort of excuse, which I have forgotten, except that she evidently did not believe it.

On deck, the men were gathered around Burns. There were ominous faces among them, and mutterings of hatred and revenge; for Burns had been popular - the best-liked man among them all. Jones, wrought to the highest pitch, had even shed a few shamefaced tears, and was obliterating the humiliating memory by an extra brusqueness of manner.

We carried the injured man aft, and with such implements as I had I cleaned and dressed the wound. It needed sewing, and it seemed best to do it before he regained consciousness. Jones and Adams went below to the forecastle, therefore, and brought up my amputating set, which contained, besides its knives, some curved needles and surgical silk, still in good condition.

I opened the case, and before the knives, the long surgeon’s knives which were in use before the scalpel superseded them, they fell back, muttering and amazed.

I did not know that Elsa Lee also was watching until, having requested Jones, who had been a sailmaker, to thread the needles, his trembling hands refused their duty. I looked up, searching the group for a competent assistant, and saw the girl. She had dressed, and the light from the lantern beside me on the deck threw into relief her white figure among the dark ones. She came forward as my eyes fell on her.

“Let me try,” she said; and, kneeling by the lantern, in a moment she held out the threaded needle. Her hand was quite steady. She made an able assistant, wiping clean the oozing edges of the wound so that I could see to clip the bleeding vessels, and working deftly with the silk and needles to keep me supplied. My old case yielded also a roll or so of bandage. By the time Burns was attempting an incoordinate movement or two, the operation was over and the instruments put out of sight.

His condition was good. The men carried him to the tent, where Jones sat beside him, and the other men stood outside, uneasy and watchful, looking in.

The operating-case, with its knives, came in for its share of scrutiny, and I felt that an explanation was due the men. To tell the truth, I had forgotten all about the case. Perhaps I swaggered just a bit as I went over to wash my hands. It was my first opportunity, and I was young, and the Girl was there.

“I see you looking at my case, boys,” I said. “Perhaps I’m a little late explaining, but I guess after what you’ve seen you’ll understand. The case belonged to my grandfather, who was a surgeon. He was in the war. That case was at Gettysburg.”

“And because of your grandfather you brought it on shipboard!” Clarke said nastily.

“No. I’m a cub doctor myself. I’d been sick, and I needed the sea and a rest.”

They were not so impressed as I had expected - or perhaps they had known all along. Sailors are a secretive lot.

“I’m thinking we’ll all be getting a rest soon,” a voice said. “What are you going to do with them knives?”

I had an inspiration. “I’m going to leave that to you men,” I said. “You may throw them overboard, if you wish - but, if you do, take out the needles and the silk; we may need them.”

There followed a savage but restrained argument among the men. Jones, from the tent, called out irritably: -

“Don’t be fools, you fellows. This happened while Leslie was asleep. I’ll swear he never moved after he lay down.”

The crew reached a decision shortly after that, and came to me in a body.

“We think,” Oleson said, “that we’ll lock them in the captain’s cabin, with the axe.”

“Very well,” I said. “Burns has the key around his neck.”

Clarke, I think it was, went into the tent, and came out again directly.

“There’s no key around his neck,” he said gruffly.

“It may have slipped around under his back.”

“It isn’t there at all.”

I ran into the tent, where Jones, having exhausted the resources of the injured man’s clothing, was searching among the blankets on which he lay. There was no key. I went out to the men again, bewildered. The dawn had come, a pink and rosy dawn that promised another stifling day. It revealed the disarray of the deck - he basins, the old mahogany amputating-case with its lock plate of bone, the stained and reddened towels; and it showed the brooding and overcast faces of the men.

“Isn’t it there?” I asked. “Our agreement was for me to carry the key to Singleton’s cabin and Burns the captain’s.”

Miss Lee, by the rail, came forward slowly, and looked up at me.

“Isn’t it possible,” she said, “that, knowing where the key was, some one wished to get it, and so -” She indicated the tent and Burns.

I knew then. How dull I had been, and stupid! The men caught her meaning, too, and we tramped heavily forward, the girl and I leading.

The door into the captain’s room was open, and the axe was gone from the bunk. The key, with the cord that Burns had worn around his neck, was in the door, the string torn and pulled as if it had been jerked away from the unconscious man. Later on we verified this by finding, on the back of Bums’s neck an abraded line two inches or so in length.

It was a strong cord - the kind a sailor pins his faith to, and uses indiscriminately to hold his trousers or his knife.

I ordered a rigid search of the deck, but the axe was gone. Nor was it ever found. It had taken its bloody story many fathoms deep into the old Atlantic, and hidden it, where many crimes have been hidden, in the ooze and slime of the sea-bottom.

That day was memorable for more than the attack on Burns. It marked a complete revolution in my idea of the earlier crimes, and of the criminal.

Two things influenced my change of mental attitude. The attack on Burns was one. I did not believe that Turner had strength enough to fell so vigorous a man, even with the capstan bar which we found lying near by. Nor could he have jerked and broken the amberline. Mrs. Johns I eliminated for the same reason, of course. I could imagine her getting the

Comments (0)