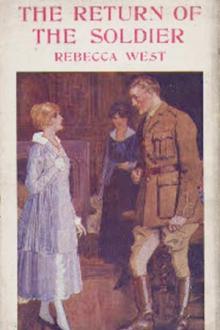

The Return of the Soldier - Rebecca West (most popular ebook readers txt) 📗

- Author: Rebecca West

- Performer: -

Book online «The Return of the Soldier - Rebecca West (most popular ebook readers txt) 📗». Author Rebecca West

Kitty read from the card:

“‘Mrs. William Grey, Mariposa, Ladysmith Road, Wealdstone,’ I don’t know anybody in Wealdstone.” That is the name of the red suburban stain which fouls the fields three miles nearer London than Harrowweald. One cannot now protect one’s environment as one once could. “Do I know her, Ward? Has she been here before?”

“Oh, no, ma’am.” The parlor-maid smiled superciliously. “She said she had news for you.” From her tone one could deduce an over-confiding explanation made by a shabby visitor while using the door-mat almost too zealously.

Kitty pondered, then said:

“I’ll come down.” As the girl went, Kitty took up the amber hair-pins from her lap and began swathing her hair about her head. “Last year’s fashion,” she commented; “but I fancy it’ll do for a person with that sort of address.” She stood up, and threw her little silk dressing-jacket over the rocking-horse. “I’m seeing her because she may need something, and I specially want to be kind to people while Chris is away. One wants to deserve well of heaven.” For a minute she was aloof in radiance, but as we linked arms and went out into the corridor she became more mortal, with a pout. “The people that come breaking into one’s nice, quiet day!” she moaned reproachfully, and as we came to the head of the broad staircase she leaned over the white balustrade to peer down on the hall, and squeezed my arm. “Look!” she whispered.

Just beneath us, in one of Kitty’s prettiest chintz armchairs, sat a middle-aged woman. She wore a yellowish raincoat and a black hat with plumes. The sticky straw hat had only lately been renovated by something out of a little bottle bought at the chemist’s. She had rolled her black thread gloves into a ball on her lap, so that she could turn her gray alpaca skirt well above her muddy boots and adjust its brush-braid with a seamed red hand that looked even more worn when she presently raised it to touch the glistening flowers of the pink azalea that stood on a table beside her. Kitty shivered, then muttered:

“Let’s get this over,” and ran down the stairs. On the last step she paused and said with conscientious sweetness, “Mrs. Grey?”

“Yes,” answered the visitor. She lifted to Kitty a sallow and relaxed face the expression of which gave me a sharp, pitying pang of prepossession in her favor: it was beautiful that so plain a woman should so ardently rejoice in another’s loveliness. “Are you Mrs. Baldry?” she asked, almost as if she were glad about it, and stood up. The bones of her bad stays clicked as she moved. Well, she was not so bad. Her body was long and round and shapely, and with a noble squareness of the shoulders; her fair hair curled diffidently about a good brow; her gray eyes, though they were remote, as if anything worth looking at in her life had kept a long way off, were full of tenderness; and though she was slender, there was something about her of the wholesome, endearing heaviness of the ox or the trusted big dog. Yet she was bad enough. She was repulsively furred with neglect and poverty, as even a good glove that has dropped down behind a bed in a hotel and has lain undisturbed for a day or two is repulsive when the chambermaid retrieves it from the dust and fluff.

She flung at us as we sat down:

“My general maid is sister to your second housemaid.”

It left us at a loss.

“You’ve come about a reference?” asked Kitty.

“Oh, no. I’ve had Gladys two years now, and I’ve always found her a very good girl. I want no reference.” With her finger-nail she followed the burst seam of the dark pigskin purse that slid about on her shiny alpaca lap. “But girls talk, you know. You mustn’t blame them.” She seemed to be caught in a thicket of embarrassment, and sat staring up at the azalea.

With the hardness of a woman who sees before her the curse of women’s lives, a domestic row, Kitty said that she took no interest in servants’ gossip.

“Oh, it isn’t—” her eyes brimmed as though we had been unkind—“servants’ gossip that I wanted to talk about. I only mentioned Gladys”—she continued to trace the burst seam of her purse—“because that is how I heard you didn’t know.”

“What don’t I know?”

Her head drooped a little.

“About Mr. Baldry. Forgive me, I don’t know his rank.”

“Captain Baldry,” supplied Kitty, wonderingly. “What is it that I don’t know?”

She looked far away from us, to the open door and its view of dark pines and pale March sunshine, and appeared to swallow something.

“Why, that he’s hurt,” she gently said.

“Wounded, you mean?” asked Kitty.

Her rusty plumes oscillated as she moved her mild face about with an air of perplexity.

“Yes,” she said, “he’s wounded.”

Kitty’s bright eyes met mine, and we obeyed that mysterious human impulse to smile triumphantly at the spectacle of a fellow-creature occupied in baseness. For this news was not true. It could not possibly be true. The War Office would have wired to us immediately if Chris had been wounded. This was such a fraud as one sees recorded in the papers that meticulously record squalor in paragraphs headed, “Heartless Fraud on Soldier’s Wife.” Presently she would say that she had gone to some expense to come here with her news and that she was poor, and at the first generous look on our faces there would come some tale of trouble that would disgust the imagination by pictures of yellow-wood furniture that a landlord oddly desired to seize and a pallid child with bandages round its throat. I cast down my eyes and shivered at the horror. Yet there was something about the physical quality of the woman, unlovely though she was, which preserved the occasion from utter baseness. I felt sure that had it not been for the tyrannous emptiness of that evil, shiny pigskin purse that jerked about on her trembling knees the poor driven creature would have chosen ways of candor and gentleness. It was, strangely enough, only when I looked at Kitty and marked how her brightly colored prettiness arched over this plain criminal as though she were a splendid bird of prey and this her sluggish insect food that I felt the moment degrading.

Kitty was, I felt, being a little too clever over it.

“How is he wounded?” she asked.

The caller traced a pattern on the carpet with her blunt toe.

“I don’t know how to put it; he’s not exactly wounded. A shell burst—”

“Concussion?” suggested Kitty.

She answered with an odd glibness and humility, as though tendering us a term she had long brooded over without arriving at comprehension, and hoping that our superior intelligences would make something of it:

“Shell-shock.” Our faces did not illumine, so she dragged on lamely, “Anyway, he’s not well.” Again she played with her purse. Her face was visibly damp.

“Not well? Is he dangerously ill?”

“Oh, no.” She was too kind to harrow us. “Not dangerously ill.”

Kitty brutally permitted a silence to fall. Our caller could not bear it, and broke it in a voice that nervousness had turned to a funny, diffident croak.

“He’s in the Queen Mary Hospital at Boulogne.” We did not speak, and she began to flush and wriggle on her seat, and stooped forward to fumble under the legs of her chair for her umbrella. The sight of its green seams and unveracious tortoiseshell handle disgusted Kitty into speech.

“How do you know all this?”

Our visitor met her eyes. This was evidently a moment for which she had steeled herself, and she rose to it with a catch of her breath. “A man who used to be a clerk along with my husband is in Mr. Baldry’s regiment.” Her voice croaked even more piteously, and her eyes begged: “Leave it at that! Leave it at that! If you only knew—”

“And what regiment is that?” pursued Kitty.

The poor sallow face shone with sweat.

“I never thought to ask,” she said.

“Well, your friend’s name—”

Mrs. Grey moved on her seat so suddenly and violently that the pigskin purse fell from her lap and lay at my feet. I supposed that she cast it from her purposely because its emptiness had brought her to this humiliation, and that the scene would close presently in a few quiet tears.

I hoped that Kitty would let her go without scarring her too much with words and would not mind if I gave her a little money. There was no doubt in my mind but that this queer, ugly episode in which this woman butted like a clumsy animal at a gate she was not intelligent enough to open would dissolve and be replaced by some more pleasing composition in which we would take our proper parts; in which, that is, she would turn from our rightness ashamed. Yet she cried:

“But Chris is ill!”

It took only a second for the compact insolence of the moment to penetrate, the amazing impertinence of the use of his name, the accusation of callousness she brought against us whose passion for Chris was our point of honor, because we would not shriek at her false news, the impudently bright, indignant gaze she flung at us, the lift of her voice that pretended she could not understand our coolness and irrelevance. I pushed the purse away from me with my toe, and hated her as the rich hate the poor as insect things that will struggle out of the crannies which are their decent home and introduce ugliness to the light of day. And Kitty said in a voice shaken with pitilessness:

“You are impertinent. I know exactly what you are doing. You have read in the ‘Harrow Observer’ or somewhere that my husband is at the front, and you come to tell this story because you think that you will get some money. I’ve read of such cases in the papers. You forget that if anything had happened to my husband the War Office would have told me. You should think yourself very lucky that I don’t hand you over to the police.” She shrilled a little before she came to the end. “Please go!”

“Kitty!” I breathed. I was so ashamed that such a scene should spring from Chris’s peril at the front that I wanted to go out into the garden and sit by the pond until the poor thing had removed her deplorable umbrella, her unpardonable raincoat, her poor frustrated fraud. But Mrs. Grey, who had begun childishly and deliberately. “It’s you who are being—” and had desisted simply because she realized that there were no harsh notes on her lyre, and that she could not strike these chords that others found so easy, had fixed me with a certain wet, clear, patient gaze. It is the gift of animals and those of peasant stock. From the least regarded, from an old horse nosing over a gate, or a drab in a workhouse ward, it wrings the heart. From this woman—I said checkingly:

“Kitty!” and reconciled her in an undertone. “There’s some mistake. Got the name wrong, perhaps. Please tell us all about it.”

Mrs. Grey began a forward movement like a curtsy. She was groveling after that purse. When she rose, her face was pink from stooping, and her dignity swam uncertainly in a sea of half-shed tears. She said:

“I’m

Comments (0)