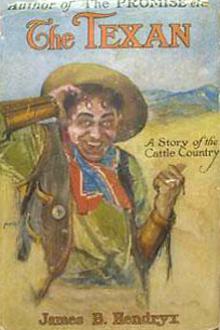

The Texan - James B. Hendryx (best historical fiction books of all time txt) 📗

- Author: James B. Hendryx

- Performer: -

Book online «The Texan - James B. Hendryx (best historical fiction books of all time txt) 📗». Author James B. Hendryx

"A'm wonder if dat girl be safe wit' him, lak' she is wit' me—bien. A'm t'ink mebbe-so dat damn good t'ing ol' Bat goin' long. If she damn fine girl mebbe-so Tex, he goin' mar' her. Dat be good t'ing. But, by Gar! if he don' mar' her, he gon' leave her 'lone. Me—A'm lak' dat Tex fine, lak' me own brudder. He got de good heart. But w'en he drink de hooch, den A'm got for look after him. He don' care wan damn 'bout nuttin'. Dat four bit in Las Vegas, dats a'right. A'm fink 'bout dat, too. But, by Gar, it tak' more'n four bit in Las Vegas for mak' of Bat let dat girl git harm."

An atmosphere of depression pervaded the group of riders as they wound in and out of the cottonwood clumps and threaded the deep coulee that led to the bench. For the most part they preserved an owlish silence, but now and then someone would break into a low, weird refrain and the others would join in with the mournful strain of "The Dying Cowboy."

"Oh, bury me not on the lone prairie-e-e,

Where the coyote howls and the wind blows free."

Or the dirge-like wail of the "Cowboy's Lament":

"Then swing your rope slowly and rattle your spurs lowly,

And give a wild whoop as you carry me along:

And in the grave throw me and roll the sod o'er me,

For I'm only a cowboy that knows he's done wrong."

"Shall we take him to Lone Tree Coulee?" asked one. Another answered disdainfully.

"Don't you know the lone tree's dead? Jest shrivelled up an' died after Bill Atwood was hung onto it. Some augers he worn't guilty. But it's better to play safe, an' string up all the doubtful ones, then yer bound to git the right one onct in a while."

"Swing over into Buffalo Coulee," commanded Tex. "There's a bunch of cottonwoods just above Hansen's old sheep ranch."

"We'll string him up to a cottonwood limb

An' dig his grave in under him——"

"Shut up!" ordered Curly, favouring the singer with a scowl. "Any one would think you was joyous-minded, which this here hangin' a man is plumb serious business, even if it hain't only a pilgrim!"

He edged his horse in beside the Texan's. "He don't seem tore up with terror, none. D'you think he's onto the racket?"

Tex shook his head, and with his eyes on the face of the prisoner which showed very white in the moonlight, rode on in silence.

"You mean you think he's jest nach'ly got guts—an' him a pilgrim?"

"How the hell do I know what he's got?" snapped the other. "Can't you wait till we get to Buffalo?"

Curly allowed his horse to fall back a few paces. "First time I ever know'd Tex to pack a grouch," he mused, as his lips drew into a grin. "He's sore 'cause the pilgrim hain't a-snifflin' an' a-carryin'-on an' tryin' to beg off. Gosh! If he turns out to be a reg'lar hand, an' steps up an' takes his medicine like a man, the joke'll be on Tex. The boys never will quit joshin' him—an' he knows it. No wonder he's sore."

The cowboys rode straight across the bench. Song and conversation had ceased and the only sounds were the low clink of bit chains and the soft rustle of horses' feet in the buffalo grass. At the end of an hour the leaders swung into an old grass-grown trail that led by devious windings into a deep, steep-sided coulee along the bottom of which ran the bed of a dried-up creek. Water from recent rains stood in brackish pools. Remnants of fence with rotted posts sagging from rusty wire paralleled their course. A dilapidated cross-fence barred their way, and without dismounting, a cowboy loosened the wire gate and threw it aside.

A deserted log-house, windowless, with one corner rotted away, and the sod roof long since tumbled in, stood upon a treeless bend of the dry creek. Abandoned implements littered the dooryard; a rusted hay rake with one wheel gone, a broken mower with cutter-bar drunkenly erect, and the front trucks of a dilapidated wagon.

The Texan's eyes rested sombrely upon the remnant of a rocking-horse, still hitched by bits of weather-hardened leather to a child's wheelbarrow whose broken wheel had once been the bottom of a wooden pail—and he swore, softly.

Up the creek he could see the cottonwood grove just bursting into leaf and as they rounded the corner of a long sheep-shed, whose soggy straw roof sagged to the ground, a coyote, disturbed in his prowling among the whitening bones of dead sheep, slunk out of sight in a weed-patch.

Entering the grove, the men halted at a point where the branches of three large trees interlaced. It was darker, here. The moonlight filtered through in tiny patches which brought out the faces of the men with grotesque distinctness and plunged them again into blackness.

Gravely the Texan edged his horse to the side of the pilgrim.

"Get off!" he ordered tersely, and Endicott dismounted.

"Tie his hands!" A cowboy caught the man's hands behind him and secured them with a lariat-rope.

The Texan unknotted the silk muffler from about his neck and folded it.

"If it is just the same to you," the pilgrim asked, in a voice that held firm, "will you leave that off?"

Without a word the muffler was returned to its place.

"Throw the rope over that limb—the big one that sticks out this way," ordered the Texan, and a cowpuncher complied.

"The knot had ort to come in under his left ear," suggested one, and proceeded to twist the noose into place.

"All ready!"

A dozen hands grasped the end of the rope.

The Texan surveyed the details critically:

"This here is a disagreeable job," he said. "Have you got anything to say?"

Endicott took a step forward, and as he faced the Texan, his eyes flashed. "Have I got anything to say!" he sneered. "Would you have anything to say if a bunch of half-drunken fools decided to take the law into their own hands and hang you for defending a woman against the brutal attack of a fiend?" He paused and wrenched to free his hands but the rope held firm. "It was a wise precaution you took when you ordered my hands tied—a precaution that fits in well with this whole damned cowardly proceeding. And now you ask me if I have anything to say!" He glanced into the faces of the cowboys who seemed to be enjoying the situation hugely.

"I've got this to say—to you, and to your whole bunch of grinning hyenas: If you expect me to do any begging or whimpering, you are in for a big disappointment. There is one request I am going to make—and that you won't grant. Just untie my hands for ten minutes and stand up to me bare-fisted. I want one chance before I go, to fight you, or any of you, or all of you! Or, if you are afraid to fight that way, give me a pistol—I never fired one until tonight—and let me shoot it out with you. Surely men who swagger around with pistols in their belts, and pride themselves on the use of them, ought not to be afraid to take a chance against a man who has never but once fired one!" There was an awkward pause and the pilgrim laughed harshly: "There isn't an ounce of sporting blood among you! You hunt in packs like the wolves you are—twenty to one—and that one with a rope around his neck and his hands tied!"

"The odds is a little against you," drawled the Texan. "Where might you hail from?"

"From a place where they breed men—not curs."

"Ain't you afraid to die?"

"Just order your hounds to jerk on that rope and I'll show you whether or not I am afraid to die. But let me tell you this, you damned murderer! If any harm comes to that girl—to Miss Marcum—may the curse of God follow every last one of you till you are damned in a fiery hell! You will kill me now, but you won't be rid of me. I'll haunt you every one to your graves. I will follow you night and day till your brains snap and you go howling to hell like maniacs."

Several of the cowboys shuddered and turned away. Very deliberately the Texan rolled a cigarette.

"There is a box in my coat pocket, will you hand me one? Or is it against the rules to smoke?" Without a word the Texan complied, and as he held a match to the cigarette he stared straight into the man's eyes: "You've started out good," he remarked gravely. "I'm just wonderin' if you can play your string out." With which enigmatical remark he turned to the cowboys: "The drinks are on me, boys. Jerk off that rope, an' go back to town! An' remember, this lynchin' come off as per schedule."

Alone in the cottonwood grove, with little patches of moonlight filtering through onto the new-sprung grass, the two men faced each other. Without a word the cowboy freed the prisoner's hands.

"Viewin' it through a lariat-loop, that way, the country looks better to a man than what it really is," he observed, as the other stretched his arms above his head.

"What is the meaning of all this? The lynching would have been an atrocious injustice, but if you did not intend to hang me why should you have taken the trouble to bring me out here?"

"'Twasn't no trouble at all. The main thing was to get you out of Wolf River. The lynchin' part was only a joke, an' that's on us. You bein' a pilgrim, that way, we kind of thought——"

"A what?"

"A pilgrim, or tenderfoot, or greener or chechako, or counter-jumper, owin' to what part of the country you misfit into. We thought you wouldn't have no guts, an' we'd——"

"Any what?"

The Texan regarded the other hopelessly. "Oh hell!" he muttered disgustedly. "Can't you talk no English? Where was you raised?"

The other laughed. "Go on, I will try to follow you."

"I can't chop 'em up no finer than one syllable. But I'll shorten up the dose sufficient for your understandin' to grasp. It's this way: D'you know what a frame-up is?"

Endicott nodded.

"Well, Choteau County politics is in such a condition of onwee that a hangin' would be a reg'lar tonic for the party that's in; which it's kind of bogged down into an old maid's tea party. Felonious takin's-off has be'n common enough, but there hasn't no hangin's resulted, for the reason that in every case the hangee has got friends or relations of votin' influence. Now, along comes you without no votin' connections an' picks off Purdy, which he's classed amongst human bein's, an' is therefore felonious to kill. There ain't nothin' to it. They'd be poundin' away on the scaffold an' testin' the rope while the trial was goin' on. Besides which you'd have to linger in a crummy jail for a couple of months waitin' for the grand jury to set on you. A few of us boys seen how things was framed an' we took the liberty to turn you loose, not because we cared a damn about you, but we'd hate to see even a snake hung fer killin' Purdy which his folks done a wrong to humanity by raisin' him.

"The way the thing is now, if the boys plays the game accordin' to Hoyle, there won't be no posses out huntin' you 'cause folks will all think you was lynched. But even if they is a posse or two, which the chances is there will be, owin' to the loosenin' effect of spiritorious licker on the tongue, which it will be indulged in liberal when that bunch hits town, we can slip down into the bad lands an' lay low for a while, an' then on to the N. P. an' you can get out

Comments (0)