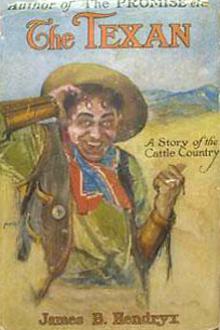

The Texan - James B. Hendryx (best historical fiction books of all time txt) 📗

- Author: James B. Hendryx

- Performer: -

Book online «The Texan - James B. Hendryx (best historical fiction books of all time txt) 📗». Author James B. Hendryx

Endicott extended his hand: "I thank you," he said. "It is certainly white of you boys to go out of your way to help a perfect stranger. I have no desire to thrust my neck into a noose to further the ends of politics. One experience of the kind is quite sufficient."

"Never mind oratin' no card of thanks. Just you climb up into the middle of that bronc an' we'll be hittin' the trail. We got quite some ridin' to do before we get to the bad lands—an' quite some after."

Endicott reached for the bridle reins of his horse which was cropping grass a few feet distant.

"But Alice—Miss Marcum!" With the reins in his hand he faced the Texan. "I must let her know I am safe. She will think I have been lynched and——"

"She's goin' along," interrupted the Texan, gruffly.

"Going along!"

"Yes, she was bound to see you through because what you done was on her account. Bat an' her'll be waitin' for us at Snake Creek crossin'."

"Who is Bat?"

"He's a breed."

"A what?"

"Wait an' see!" growled Tex. "Come on; we can't set here 'til you get educated. You'd ought to went to school when you was young."

Endicott reached for a stirrup and the horse leaped sidewise with a snort of fear. Again and again the man tried to insert a foot into the broad wooden stirrup, but always the horse jerked away. Round and round in a circle they went, while the Texan sat in his saddle and rolled a cigarette.

"Might try the other one," he drawled, as he struck a match. "Don't you know no better than to try to climb onto a horse on the right-hand side? You must of be'n brought up on G-Dots."

"What's a G-Dot?"

"There you go again. Do I look like a school-marm? A G-Dot is an Injun horse an' you can get on 'em from both sides or endways. Come on; Snake Creek crossin' is a good fifteen miles from here, an' we better pull out of this coulee while the moon holds."

Endicott managed to mount, and gathering up the reins urged his horse forward. But the animal refused to go and despite the man's utmost efforts, backed farther and farther into the brush.

"Just shove on them bridle reins a little," observed the Texan dryly. "I think he's swallerin' the bit. What you got him all yanked in for? D'you think the head-stall won't hold the bit in? Or ain't his mouth cut back far enough to suit you? These horses is broke to be rode with a loose rein. Give him his head an' he'll foller along."

A half-mile farther up the coulee, the Texan headed up a ravine that led to the level of the bench, and urging his horse into a long swinging trot, started for the mountains. Mile after mile they rode, the cowboy's lips now and then drawing into their peculiar smile as, out of the corner of his eye he watched the vain efforts of his companion to maintain a firm seat in the saddle. "He's game, though," he muttered, grudgingly. "He rides like a busted wind-mill an' it must be just tearin' hell out of him but he never squawks. An' the way he took that hangin'—— If he'd be'n raised right he'd sure made some tough hand. An' pilgrim or no pilgrim, the guts is there."

CHAPTER X THE FLIGHTWhen the Texan had departed Bat Lajune eyed the side-saddle with disgust. "Dat damn t'ing, she ain' no good. A'm git de reg'lar saddle."

Slowly he pushed open the side door of the hotel and paused in the darkened hallway to stare at the crack of yellow light that showed beneath the door of Number 11.

"A'm no lak' dis fool 'roun' wit' 'omen." He made a wry face and knocked gingerly.

Jennie Dodds opened the door, and for a moment eyed the half-breed with frowning disfavour.

"Look a here, Bat Lajune, is this on the level? They say you're the squarest Injun that ever swung a rope. But Injun or white, you're a man, an' I wouldn't trust one as far as I could throw a mule by the tail."

"Mebbe-so you lak' you com' 'long an' see, eh?"

"I got somethin' else to do besides galavantin' 'round the country nights with cowboys an' Injuns."

The half-breed laughed and turned to Alice. "Better you bor' some pants for ride de horse. Me, A'm gon' git nudder saddle. 'Fore you ride little ways you bre'k you back."

"Go over to the livery barn an' tell Ross to put my reg'lar saddle on in place of the side-saddle, an' when you come back she'll be ready." Jennie Dodds slipped from the room as the outer door closed upon the half-breed's departure, and returned a few minutes later with her own riding outfit, which she tossed onto the bed.

"Jest you climb into them, dearie," she said. "Bat's right. Them side-saddles is sure the dickens an' all, if you got any ways to go."

"But," objected Alice, "I can't run off with all your things this way!" She reached for her purse. "I'll tell you, I'll buy them from you, horse and all!"

"No you won't, no such thing!" Jennie Dodds assumed an injured tone. "Pity a body can't loan a friend nuthin' without they're offered to git payed for it. You can send the clothes back when you're through with 'em. An' here's a sack. Jest stick what you need in that. It'll tie on behind your saddle, an' you can leave the rest of your stuff here in your grip an I'll ship it on when you're ready for it. Better leave them night-gowns an' corsets an' such like here. You ain't goin' to find no use for 'em out there amongst the prickly pears an' sage brush. Law me! I don't envy you your trip none! I'd jest like to know what for devilment that Tex Benton's up to. Anyways, you don't need to be afraid of him—like Purdy. But men is men, an' you got to watch 'em."

As the girl chattered on she helped Alice to dress for the trail and when the "war-bag" was packed and tied with a stout cord, the girl crossed to the window and drew back the shade.

"The Injun's back. You better be goin'." The girl slipped a small revolver from her pocket and pressed it into Alice's hand. "There's a pocket for it in the bloomers. Cinnabar Joe give it to me a long time ago. Take care of yourself an' don't be afraid to use it if you have to. An' mind you let me hear jest the minute you git anywheres. I'll be a-dyin' to know what become of you."

Alice promised and as she passed through the door, leaned swiftly and kissed the girl squarely upon the lips.

"Good-bye," she whispered. "I won't forget you," and the next moment she stepped out to join the waiting half-breed, who with a glance of approval at her costume, took the bag from her hand and proceeded to secure it behind the cantle. The girl mounted without assistance, and snubbing the lead-rope of the pack-horse about the horn of his saddle, the half-breed led off into the night.

Hour after hour they rode in silence, following a trail that wound in easy curves about the bases of hillocks and small buttes, and dipped and slanted down the precipitous sides of deep coulees where the horses' feet splashed loudly in the shallow waters of fords. As the moon dipped lower and lower, they rode past the darkened buildings of ranches nestled beside the creeks, and once they passed a band of sheep camped near the trail. The moonlight showed a sea of grey, woolly backs, and on a near-by knoll stood a white-covered camp-wagon, with a tiny lantern burning at the end of the tongue. A pair of hobbled horses left off snipping grass beside the trail and gazed with mild interest as the two passed, and beneath the wagon a dog barked. At length, just as the moon sank from sight behind the long spur of Tiger Butte, the trail slanted into a wide coulee from the bottom of which sounded the tinkle of running water.

"Dis Snake Creek," remarked the Indian; "better you git off now an' stretch you leg. Me, A'm mak' de blanket on de groun' an' you ketch-um little sleep. Mebbe-so dem com' queek—mebbe-so long tam'."

Even as he talked the man spread a pair of new blankets beside the trail and walking a short distance away seated himself upon a rock and lighted a cigarette.

With muscles aching from the unaccustomed strain of hours in the saddle, Alice threw herself upon the blankets and pillowed her head on the slicker that the half-breed had folded for the purpose. Almost immediately she fell asleep only to awake a few moments later with every bone in her body registering an aching protest at the unbearable hardness of her bed. In vain she turned from one side to the other, in an effort to attain a comfortable position. With nerves shrieking at each new attitude, all thought of sleep vanished and the girl's brain raced madly over the events of the past few hours. Yesterday she had sat upon the observation platform of the overland train and complained to Endicott of the humdrum conventionality of her existence! Only yesterday—and it seemed weeks ago. The dizzy whirl of events that had snatched her from the beaten path and deposited her somewhere out upon the rim of the world had come upon her so suddenly and with such stupendous import that it beggared any attempt to forecast its outcome. With a shudder she recalled the moment upon the verge of the bench when in a flash she had realized the true character of Purdy and her own utter helplessness. With a great surge of gratitude—and—was it only gratitude—this admiration and pride in the achievement of the man who had rushed to her rescue? Alone there in the darkness the girl flushed to the roots of her hair as she realized that it was for this man she had unhesitatingly and unquestioningly ridden far into the night in company with an unknown Indian. Realized, also, that above the pain of her tortured muscles, above the uncertainty of her own position, was the anxiety and worry as to the fate of Endicott. Where was he? Had Tex lied when he told her there would be no lynching? Even if he desired could he prevent the cowboys from wreaking their vengeance upon the man who had killed one of their number? She recalled with a shudder the cold cynicism of the smile that habitually curled the lips of the Texan. A man who could smile like that could lie—could do anything to gain an end. And yet—she realized with a puzzled frown that in her heart was no fear of him—no terror such as struck into her very soul at the sudden unmasking of Purdy. "It's his eyes," she murmured; "beneath his cynical exterior lies a man of finer fibre."

Some distance away a match flared in the darkness and went out, and dimly by the little light of the stars Alice made out the form of the half-breed seated upon his rock beside the trail. Motionless as the rock itself the man sat humped over with his arms entwining his knees. A sombre figure, and one that fitted intrinsically into the scene—the dark shapes of the three horses that snipped grass beside the trail, the soft murmur of the waters of the creek as they purled over the stones, the black wall of the coulee, with the mountains rising beyond—all bespoke the wild that since childhood she had pictured, but never before had seen. Under any other circumstances the setting would have appealed, would have thrilled her to the soul. But now—over and over through her brain repeated the question: Where is he?

A horse nickered softly and raising his head, sniffed the night air. The Indian stepped from his rock and stood alert with his eyes on the reach of the

Comments (0)