The Texan - James B. Hendryx (best historical fiction books of all time txt) 📗

- Author: James B. Hendryx

- Performer: -

Book online «The Texan - James B. Hendryx (best historical fiction books of all time txt) 📗». Author James B. Hendryx

"I am certainly obliged to you," laughed Endicott, "for going to all that trouble to provide me with clothing. And by the way, did you learn anything—in regard to posses, I mean?"

The Texan nodded sombrely: "Yep. I did. This here friend of mine was on his way back from Wolf River when I met up with him. 'Tex,' he says, 'where's the pilgrim?' I remains noncommital, an' he continues, 'I layed over yesterday to enjoy Purdy's funeral, which it was the biggest one ever pulled off in Wolf River—not that any one give a damn about Purdy, but they've drug politics into it, an' furthermore, his'n was the only corpse to show for the whole celebration, it bein' plumb devoid of further casualties.'" The cowpuncher paused, referred to his bottle, and continued: "It's just like I told you before. There can't no one's election get predjudiced by hangin' you, an' they've made a kind of issue out of it. There's four candidates for sheriff this fall an' folks has kind of let it be known, sub rosy, that the one that brings you in, gathers the votes. In the absence of any corpse delecti, which in this case means yourn, folks refuses to assume you was hung, so each one of them four candidates is right now scouring the country with a posse. All this he imparts to me while he was throwin' that outfit of clothes together an' further he adds that I'm under suspicion for aidin' an' abettin', an' that means life with hard labour if I'm caught with the goods—an', Win, you're the goods. Therefore, you'll confer a favour on me by not getting caught, an' incidentally save yourself a hangin'. Once we get into the bad lands we're all to the good, but even then you've got to keep shy of folks. Duck out of sight when you first see any one. Don't have nothin' to say to no one under no circumstances. If you do chance onto someone where you can't do nothin' else you'll have to lie to 'em. Personal, I don't favour lyin' only as a last resort, an' then in moderation. Of course, down in the bad lands, most of the folks will be on the run like we are, an' not no more anxious for to hold a caucus than us. You don't have to be so particular there, 'cause likely all they'll do when they run onto you will be to take a shot at you, an' beat it. We've got to lay low in the bad lands about a week or so, an' after that folks will have somethin' else on their mind an' we can slip acrost to the N. P."

"See here, Tex, this thing has gone far enough." There was a note of determination in Endicott's voice as he continued: "I cannot permit you to further jeopardize yourself on my account. You have already neglected your business, incurred no end of hard work, and risked life, limb, and freedom to get me out of a scrape. I fully appreciate that I am already under heavier obligation to you than I can ever repay. But from here on, I am going it alone. Just indicate the general direction of the N. P. and I will find it. I know that you and Bat will see that Miss Marcum reaches the railway in safety, and——"

"Hold on, Win! That oration of yourn ain't got us no hell of a ways, an' already it's wandered about four school-sections off the trail. In the first place, it's me an' not you that does the permittin' for this outfit. I've undertook to get you acrost to the N. P. I never started anythin' yet that I ain't finished. Take this bottle of hooch here—I've started her, an' I'll finish her. There's just as much chance I won't take you acrost to the N. P., as that I won't finish that bottle—an' that's damn little.

"About neglectin' my business, as you mentioned, that ain't worryin' me none, because the wagon boss specified particular an' onmistakeable that if any of us misguided sons of guns didn't show up on the job the mornin' followin' the dance, we might's well keep on ridin' as far as that outfit was concerned, so it's undoubtable that the cow business is bein' carried on satisfactory durin' my temporary absence.

"Concernin' the general direction of the N. P., I'll enlighten you that if you was to line out straight for Texas, it would be the first railroad you'd cross. But you wouldn't never cross it because interposed between it an' here is a right smart stretch of country which for want of a worse name is called the bad lands. They's some several thousan' square miles in which there's only seven water-holes that a man can drink out of, an' generally speakin' about five of them is dry. There's plenty of water-holes but they're poison. Some is gyp an' some is arsnic. Also these here bad lands ain't laid out on no general plan. The coulees run hell-west an' crossways at their littlest end an' wind up in a mud crack. There ain't no trails, an' the inhabitants is renegades an' horse-thieves which loves their solitude to a murderous extent. If a man ain't acquainted with the country an' the horse-thieves, an' the water-holes, his sojourn would be discouragin' an' short.

"All of which circumlocutin' brings us to the main point which is that she wouldn't stand for no such proceedin'. As far as I can see that settles the case. The pros an' cons that you an' me could set here an' chew about, bein' merely incidental, irreverent, an' by way of passin' the time."

Endicott laughed: "You are a philosopher, Tex."

"A cow-hand has got to be."

"But seriously, I could slip away without her knowing it, then the only thing you could do would be to take her to the railway."

"Yes. Well, you try that an' you'll find out who's runnin' this outfit. I'll trail out after you an' when I catch you, I'll just naturally knock hell out of you, an' that's all there'll be to it. You had the edge on me in the water but you ain't on land. An' now that's settled to the satisfaction of all parties concerned, suppose me an' you slip over to camp an' cook supper so we can pull out right after sundown."

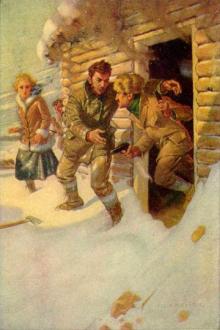

The two made their way through the timber to find Alice blowing herself red in the face in a vain effort to coax a blaze out of a few smouldering coals she had scraped from beneath the ashes of the fire.

"Hold on!" cried the Texan, striding toward her, "I've always maintained that buildin' fires is a he-chore, like swearin', an' puttin' the baby to sleep. So, if you'll just set to one side a minute while I get this fire a-goin' an' Win fetches some water, you can take holt an' do the cookin' while we-all get the outfit ready for the trail."

Something in the man's voice caused the girl to regard him sharply, and her eyes shifted for a moment to his companion who stood in the background. There was no flash of recognition in the glance, and Endicott, suppressing a laugh, turned his face away, picked up the water pail, and started toward the creek.

"Who is that man?" asked the girl, a trifle nervously, as he disappeared from view.

"Who, him?" The Texan was shaving slivers from a bull pine stick. "He's a friend of mine. Win's his name, an' barrin' a few little irregularities of habit, he ain't so bad." The cowboy burst into mournful song as he collected his shavings and laid them upon the coals:

"It's little Joe, the wrangler, he'll wrangle never more,

His days with the remuda they are o'er;

'Twas a year ago last April when he rode into our camp,

Just a little Texas stray, and all alo-o-o-n-e."

Alice leaned toward the man in sudden anger:

"You've been drinking!" she whispered.

Tex glanced at her in surprise: "That's so," he said, gravely. "It's the only way I can get it down."

She was about to retort when Endicott returned from the creek and placed the water pail beside her.

"Winthrop!" she cried, for the first time recognizing him. "Where in the world did you get those clothes, and what is the matter with your face?"

Endicott grinned: "I shaved myself for the first time."

"What did you do it with, some barbed wire?"

"Looks like somethin' that was left out in the rain an' had started to peel," ventured the irrepressible Tex.

Alice ignored him completely. "But the clothes? Where did you get them?"

Endicott nodded toward the Texan. "He loaned them to me!"

"But—surely they would never fit him."

"Didn't know it was necessary they should," drawled Tex, and having succeeded in building the fire, moved off to help Bat who was busying himself with the horses.

"Where has he been?" asked the girl as the voice of the Texan came from beyond the trees:

"It happened in Jacksboro in the spring of seventy-three,

A man by the name of Crego come steppin' up to me,

Sayin', 'How do you do, young fellow, an' how would you like to go

An' spend one summer pleasantly, on the range of the buffalo-o-o?'"

"I'm sure I don't know. He came back an hour or so ago and woke me up and gave me this outfit and told me my whiskers looked like the infernal regions and that I had better shave—even offered to shave me, himself."

"But he has been drinking. Where did he get the liquor?"

"The same place he got the clothes, I guess. He said he met a friend and borrowed them," smiled Endicott.

"Well, it's nothing to laugh at. I should think you'd be ashamed to stand there and laugh about it."

The man stared at her in surprise. "I guess he won't drink enough to hurt him any. And—why, it was only a day or two ago that you sat in the dining car and defended their drinking. You even said, I believe, that had you been a man you would have been over in the saloon with them."

"Yes, I did say that! But that was different. Oh, I think men are disgusting! They're either bad, or just plain dumb!"

"We left old Crego's bones to bleach on the range of the buffalo—

Went home to our wives an' sweethearts, told others not to go,

For God's forsaken the buffalo range, and the damned old buffalo-o-o!"

"At least our friend Tex does not seem to be stricken with dumbness," Endicott smiled as the words of the buffalo skinner's song broke forth anew. "Do you know I have taken a decided fancy to him. He's——"

"I'd run along and play with him then if I were you," was the girl's sarcastic comment. "Maybe if you learn how to swear and sing some of his beautiful songs he'll give you part of his whiskey." She turned away abruptly and became absorbed in the preparation of supper, and Endicott, puzzled as he was piqued, at the girl's attitude, joined the two who were busy with the pack. "He's just perfectly stunning in that outfit," thought Alice as she watched him disappear in the timbers. "Oh, I don't know—sometimes I wish—" but the wish became confused somehow with the sizzling of bacon. And with tight-pressed lips, she got out the tin dishes.

"What's the matter, Win—steal a sheep?" asked the Texan as he paused, blanket in hand, to regard Endicott.

"What?"

"What did you catch hell for? You didn't imbibe no embalmin' fluid."

Endicott grinned and the cowboy finished rolling his blanket.

"Seems like we're in bad, some way. She didn't say nothin' much, but I managed to gather from the way she looked right through the place where I was standin' that I could be got along without for a spell. Her interruptin' me right in the middle of a song to impart that I'd be'n drinkin' kind of throw'd me under the impression that the pastime was frowned on, but

Comments (0)