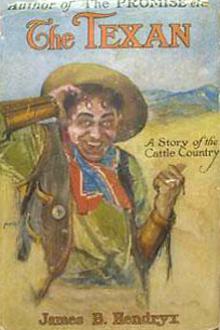

The Texan - James B. Hendryx (best historical fiction books of all time txt) 📗

- Author: James B. Hendryx

- Performer: -

Book online «The Texan - James B. Hendryx (best historical fiction books of all time txt) 📗». Author James B. Hendryx

"Come along; boys, and listen to my tale,

I'll tell you of my troubles on the old Chisholm trail.

Coma ti yi youpy, youpy ya, youpy ya,

Coma ti yi youpy, youpy ya.

I started up the trail October twenty-third,

I started up the trail with the 2-U herd.

Oh, a ten dollar hoss and a forty dollar saddle—

And I'm goin' to punchin' Texas cattle.

I woke up one morning on the old Chisholm trail,

Rope in my hand and a cow by the tail.

I'm up in the mornin' afore daylight

And afore I sleep the moon shines bright.

Old Ben Bolt was a blamed good boss,

But he'd go to see the girls on a sore-backed hoss.

Old Ben Bolt was a fine old man

And you'd know there was whiskey wherever he'd land.

My hoss throwed me off at the creek called Mud,

My hoss throwed me off round the 2-U herd.

Last time I saw him he was going cross the level

A-kicking up his heels and a-runnin' like the devil.

It's cloudy in the west, a-lookin' like rain,

An' my damned old slicker's in the wagon again.

Crippled my hoss, I don't know how,

Ropin' at the horns of a 2-U cow.

We hit Caldwell and we hit her on the fly,

We bedded down the cattle on the hill close by.

No chaps, no slicker, and it's pourin' down rain,

An' I swear, by God, I'll never night-herd again.

Feet in the stirrups and seat in the saddle,

I hung and rattled with them long-horn cattle.

Last night I was on guard and the leader broke the ranks,

I hit my horse down the shoulders and I spurred him in the flanks.

The wind commenced to blow, and the rain began to fall.

Hit looked, by grab, like we was goin' to lose 'em all.

I jumped in the saddle and grabbed holt the horn,

Best blamed cow-puncher ever was born.

I popped my foot in the stirrup and gave a little yell,

The tail cattle broke and the leaders went to hell.

I don't give a damn if they never do stop;

I'll ride as long as an eight-day clock.

Foot in the stirrup and hand on the horn,

Best damned cowboy ever was born.

I herded and I hollered and I done very well

Till the boss said, 'Boys, just let 'em go to hell.'

Stray in the herd and the boss said kill it,

So I shot him in the rump with the handle of the skillet.

We rounded 'em up and put 'em on the cars,

And that was the last of the old Two Bars.

Oh, it's bacon and beans most every day,—

I'd as soon be a-eatin' prairie hay.

I'm on my best horse and I'm goin' at a run,

I'm the quickest shootin' cowboy that ever pulled a gun.

I went to the wagon to get my roll,

To come back to Texas, dad-burn my soul.

I went to the boss to draw my roll,

He had it figgered out I was nine dollars in the hole.

I'll sell my outfit just as soon as I can,

I won't punch cattle for no damned man.

Goin' back to town to draw my money,

Goin' back home to see my honey.

With my knees in the saddle and my seat in the sky,

I'll quit punchin' cows in the sweet by and by.

Coma ti yi youpy, youpy ya, youpy ya,

Coma ti yi youpy, youpy ya."

As the last words of the chorus died away both men started at the sound of the girl's voice.

"Whenever you can spare the time you will find your supper ready," she announced, coldly, and without waiting for a reply, turned toward the camp. Endicott looked at Tex, and Tex looked at Endicott.

"Seems like you done raised hell again, Win. Standin' around listenin' to ribald songs, like you done, ain't helped our case none. Well, we better go eat it before she throws it away. Come on, Bat, you're included in the general gloom. Your face looks like a last year's circus bill, Win, with them patches of paper hangin' to it. Maybe that's what riled her. If I thought it was I'd yank 'em off an' let them cuts bleed no matter how bad they stung, just to show her my heart's in the right place. But that might not suit, neither, so there you are."

Alice sat well back from the fire as the three men poured their coffee and helped themselves to the food.

"Ain't you goin' to join us in this here repast?" asked Tex, with a smile.

"I have eaten, thank you."

"You're welcome—like eight dollars change for a five-spot."

In vain Endicott signalled the cowboy to keep silent. "Shove over, Win, you're proddin' me in the ribs with your elbow! Ain't Choteau County big enough to eat in without crowdin'? 'Tain't as big as Tom Green County, at that, no more'n Montana is as big as Texas—nor as good, either; not but what the rest of the United States has got somethin' to be said in its favour, though. But comparisons are ordorous, as the Dutchman said about the cheese. Come on, Win, me an' you'll just wash up these dishes so Bat can pack 'em while we saddle up."

A half-hour later, just as the moon topped the crest of a high ridge, the four mounted and made their way down into the valley.

"We got to go kind of easy for a few miles 'cause I shouldn't wonder if old man Johnson had got a gang out interrin' defunck bovines. I'll just scout out ahead an' see if I can locate their camp so we can slip past without incurrin' notoriety."

"I should think," said Alice, with more than a trace of acid in her tone, "that you had done quite enough scouting for one day."

"In which case," smiled the unabashed Texan, "I'll delegate the duty to my trustworthy retainer an' side-kicker, the ubiquitous an' iniquitous Baterino St. Cecelia Julius Caesar Napoleon Lajune. Here, Bat, fork over that pack-horse an' take a siyou out ahead, keepin' a lookout for posses, post holes, and grave-diggers. It's up to you to see that we pass down this vale of tears, unsight an' unsung, as the poet says, or off comes your hind legs. Amen."

The half-breed grinned his understanding and handed over the lead-rope with a bit of homely advice. "You no lak' you git find, dat better you don' talk mooch. You ain' got to sing no mor', neider, or ba Goss! A'm tak' you down an' stick you mout' full of rags, lak' I done down to Chinook dat tam'. Dat hooch she mak' noise 'nough for wan night, sabe?"

"That's right, Bat. Tombstones and oysters is plumb raucous institutions to what I'll be from now on." He turned to the others with the utmost gravity. "You folks will pardon any seemin' reticence on my part, I hope. But there's times when Bat takes holt an' runs the outfit—an' this is one of 'em."

CHAPTER XIV ON ANTELOPE BUTTEAfter the departure of Bat it was a very silent little cavalcade that made its way down the valley. Tex, with the lead-horse in tow, rode ahead, his attention fixed on the trail, and the others followed, single file.

Alice's eyes strayed from the backs of her two companions to the mountains that rolled upward from the little valley, their massive peaks and buttresses converted by the wizardry of moonlight into a fairyland of wondrous grandeur. The cool night air was fragrant with the breath of growing things, and the feel of her horse beneath her caused the red blood to surge through her veins.

"Oh, it's grand!" she whispered, "the mountains, and the moonlight, and the spring. I love it all—and yet—" She frowned at the jarring note that crept in, to mar the fulness of her joy. "It's the most wonderful adventure I ever had—and romantic. And it's real, and I ought to be enjoying it more than I ever enjoyed anything in all my life. But, I'm not, and it's all because—I don't see why he had to go and drink!" The soft sound of the horses' feet in the mud changed to a series of sharp clicks as their iron shoes encountered the bare rocks of the floor of the canyon whose precipitous rock walls towered far above, shutting off the flood of moonlight and plunging the trail into darkness. The figures of the two men were hardly discernible, and the girl started nervously as her horse splashed into the water of the creek that foamed noisily over the canyon floor. She shivered slightly in the wind that sucked chill through the winding passage, although back there in the moonlight the night had been still. Gradually the canyon widened. Its walls grew lower and slanted from the perpendicular. Moonlight illumined the wider bends and flashed in silver scintillations from the broken waters of the creek. The click of the horses' feet again gave place to the softer trampling of mud, and the valley once more spread before them, broader now, and flanked by an endless succession of foothills.

Bat appeared mysteriously from nowhere, and after a whispered colloquy with Tex, led off toward the west, leaving the valley behind and winding into the maze of foothills. A few miles farther on they came again into the valley and Alice saw that the creek had dwindled into a succession of shallow pools between which flowed a tiny trickle of the water. On and on they rode, following the shallow valley. Lush grass overran the pools and clogged the feeble trickle of the creek. Farther on, even the green patches disappeared and white alkali soil showed between the gnarled sage bushes. Gradually the aspect of the country changed. High, grass-covered foothills gave place to sharp pinnacles of black lava rock, the sides of the valley once more drew together, low, and broken into ugly cutbanks of dirty grey. Sagebrush and prickly pears furnished the only vegetation, and the rough, broken surface of the country took on a starved, gaunt appearance.

Alice knew instinctively that they were at the gateway of the bad lands, and the forbidding aspect that greeted her on every side as her eyes swept the restricted horizon caused a feeling of depression. Even the name "bad lands" seemed to hold a foreboding of evil. She had not noticed this when the Texan had spoken it. If she had thought of it at all, it was impersonally—an undesirable strip of country, as one mentions the Sahara Desert. But, now, when she herself was entering it—was seeing with her own eyes the grey mud walls, the bare black rocks, and the stunted sage and cactus—the name held much of sinister portent.

From a nearby hillock came a thin weird scream—long-drawn and broken into a series of horrible cackles. Instantly, as though it were the signal that loosed the discordant chorus of hell, the sound was caught up, intensified and prolonged until the demonical screams seemed to belch from every hill and from the depths of the coulees between.

Unconsciously, the girl spurred her horse which leaped past Endicott and Bat and drew up beside the Texan, who was riding alone in the forefront.

The man glanced into the white frightened face: "Coyotes," he said, gravely. "They won't bother any one."

The girl shuddered. "There must be a million of them. What makes them howl that way?"

"Most any

Comments (0)