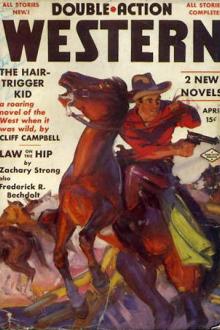

The Hair-Trigger Kid - Max Brand (uplifting novels .TXT) 📗

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid - Max Brand (uplifting novels .TXT) 📗». Author Max Brand

“I’ve had the same idea myself,” said she, “though I suppose I want to

make his case as black as possible.”

“Oh, Mother,” said the girl, “I hope I can be as honest as you are!”

“Then honestly face what a life with him would mean—no home, no

children. You wouldn’t dare to trust children to the care of such a wild

man. You know that?”

The girl was silent. Then she nodded.

“I suppose he told you how much you mean to him?”

“Not one word!”

“Ah, but a look, a gesture can fill up a big page, of course!”

“Not a look, not a gesture. Only that some things leaked through—or I

thought they did.”

“He’s cleverer, even, than I suspected!”

“Perhaps. I don’t think so. I think that he’s pulled two ways. He hates

father. He likes me. And he’s determined to break up Dixon’s crowd.”

“Do you really think so?”

“Yes. Animals mean something to him more than they do to us. I saw his

face when he heard the lowing of the cattle at Hurry Creek.”

“What are you going to do, Georgia?”

“Wait,” said Georgia, “and pray that I never see him again.” Mrs. Milman,

staring at the girl like one who hopes against hope, said simply: “I

think that you’re right, Georgia.”

Then she added. “And what about your father?”

“I’ve thought of that.”

“What are you going to do?”

“I’m going to go to him and tell him—”

“Think it over. You’ll have to have the right words.”

“I’m simply going to tell him that it doesn’t matter, whatever he’s done

in the past. Not to me. Not to you and me, Mother! Am I right?”

Elinore Milman caught a quick breath.

“We can’t let it matter. There has to be such a thing as a blind faith

and a blind loyalty, doesn’t there?”

“Yes,” said the girl. “That’s just what I feel.”

The mother stood up and put her arms around Georgia.

“We’re all standing on the brink of ruin,” she said. “Yesterday we were

rich and happy and there wasn’t a cloud in the sky. Today, there’s every

chance that we’ll go downhill and never rise again. Your father’s life is

in horrible danger from that boy. There’s a shame in his past that is

never going to take its shadow off our lives, no matter how the affair

comes out. All of our wealth seems in danger of being snatched away. And

I have you to tremble about and pray for, Georgia. There’s only the way

to face these things, and that’s together, shoulder to shoulder.”

“Yes,” said Georgia.

She began to tremble violently and suddenly her mother whispered: “I

think that you’re having the hardest time of all. But now go and tell

your father what you’ve told me, will you?”

“I’ll go at once,” said Georgia.

She turned to the door and waited there for a moment, breathing deeply to

drive away a faintness which was growing upon her. Then, composing

herself with a great effort, she went out of the house toward the barn.

She met little, one-legged Harry Sams, with a manure fork in his hand

coming from behind the barn. The stem of his corncob pipe had had a new

mouthpiece whittled and rewhittled in it. It was now hardly two inches

long, and the fumes from the bowl of the pipe kept him constantly

blinking. But he was faithful to old pipes, as to old friends.

“Harry,” she said, “have you seen Father?”

“Aye,” said Harry, “he’s gone and got him that white-faced fool of a

chestnut gelding, and he’s gone off toward Hurry Creek as though there

was guns behind him, instead of in front.”

The words struck her like bullets. All the sunset blurred and darkened

before her face, for she knew that her father had gone off in hope of

finding his death.

The Kid, when he got to the bottom of the long lariat, still found that

his feet dangled well above either water or ground. He looked down, but

all that he could see was the white dashing of the water—not white,

really, but a dusky gray in that half light. He could not tell whether

the water ran directly beneath him or if there were a small ledge of rock

at the side of the canyon bed.

Hanging by one strong hand, with the other, he took out a match and

scratched it. It was only a single spluttering of dim light before a dash

of spray put it out, but that glimpse was enough to reveal to the Kid a

raging inferno of waters. And, beneath him, a narrow, slippery ledge of

rock, hardly a single foot wide.

To the ledge he dropped.

By daylight it would have been a simple matter, perhaps, to get along the

place. And he cursed himself because he had not thought of exploring here

while the sun was still shining.

He tried matches again and again. But the wind of the water or the flying

spray itself instantly snatched away the flame. He had to explore by

touch alone. Light there was almost none, Though when he looked up, he

could see stars sprinkled across the narrow road which the canyon walls

fenced through the high heavens; and there was among them one broad-faced

planet—its name he did not know.

The thunder of the creek now pounded steadily, like the continual roar of

guns; the solid rocks trembled slightly beneath his hands; and the

absence of light gave him only vague and illusive hints of what was

around him.

Therefore he closed his eyes altogether for the purpose of shutting out

the few, faint rays which merely helped to confuse him, and he began to

fumble along the wall of the ravine.

It swung to the left for a little distance. He tried to remember just how

the creek had been seen to curve from above, but even this point he

carelessly had overlooked. However, that did not matter now. He was

committed to that bare, slippery wall of rock, and if he fell from it, he

was done forever.

That was not the only danger.

He had hardly made three steps’ progress when something crashed behind

him, and then a great black form shot by him, low down on the face of the

water.

It missed his feet in inches, grinding on the ledge of rock on which he

stood. Hurtling onward, it struck on the corner of the next big rock with

a staggering shock, then was whirled around the edge.

Vaguely he had seen this, after opening his eyes when the blow came

behind him. He knew that it was a tree trunk, torn down from the banks

higher up the stream, and now sent like a javelin, flying down toward the

lower waters. A second of these might very well strike him and dash him

to a pulp, or else flick him off from the wall like a caterpillar from a

tree, to be ground up by the teeth of the rocks.

Yet he went on. In fact, there was no return, but the grim steadiness of

his purpose never left him.

With closed eyes, and still fumbling, he worked out to a place where the

rock ledge shelved away to nothing beneath the grip of his feet. He

reached down, pulled off his boots, and prepared to see what naked hands

and feet could do with the treacherous surface of that canyon face in the

dark, with the spray whipping continually around him.

He found a handhold. His feet, reaching at the rock below, helped him a

good deal. He was working his way out and out to the left, where the

creek turned its corner, and now he turned the point of it.

It was grisly, hard work, for his weight was hanging almost entirely from

his hands. Only now and then did he get any purchase for his feet. And

the handholds were hard to find also. He had to hold by one hand and with

the other fumble before him, vaguely, up and down, until he found some

small projection, or some crevice into which even the tips of his fingers

could be fitted.

Sometimes he was swaying up. Once he descended until his feet thrust into

the water.

The current jerked at him like a hand. He almost lost his hold. For one

breathless moment he thought that he was gone.

But his hands were strong, and his hold remained true.

In this manner he found that he had turned the corner. But now his

position was not much better. There was still no foothold beneath him,

and his arms were now aching to the pits of the shoulders. They were so

extremely tired that they shook with a violence which of itself

threatened to shake him loose from the wet rock.

And there was no light!

He opened his eyes.

Yes, far away to the left there was a red star shining toward him. It

glared at him like an eye, threateningly. But suddenly, his eyes opening

more clearly, he saw that it was the flame of the Dixon camp fire.

That, which should have depressed him still more, gave him a sudden hope,

and with the hope came strength.

He could not have endured the strain of going back to the last ridge

which he had left. The very idea of turning back, however, had not come

to him. And he worked on, gritting his teeth until his jaws ached as well

as his arms.

Then, fumbling forward with his left foot, he touched a firm support.

He rested his whole weight upon the rock beneath. It was strong and firm.

At this the relief was so great that the blood bounded violently into his

head, and he was dizzy. But he clung, fighting his way through the first

moments of the reaction after the strain was over.

Still his body was shaking a little, and his arms were numb, but he began

to breathe more easily, and his mind was more at ease also.

Those who have passed through the desperate gates of an enterprise feel

that the early danger must assure them of better luck further on. At

least, so the Kid felt, as he stood there in the dark of the ravine, with

the chilly drops of snow water flicking at him.

The canyon walls opened here perceptibly, moreover, and there was

sufficient starlight to enable him to see dimly what was before him.

It was no easy road. Here the ledge ran a little distance. There it

disappeared entirely. But the walls were not so perpendicular and the

weight of his body would in no place fall so sheerly upon his tired hands

and upon his shoulders.

He swung his arms. He kneaded them with his shaking hands until the flow

of blood subdued their aching. And when at last he felt sufficient master

of himself, he resumed his progress toward the mouth of the canyon.

He had had practice now; besides, he had some sight to help him, so that

the work went on more easily, and he made good use of all his advantages

until he carne to where the very lips of the ravine spread out wider and

wider, and the opening flood of the river flattened and lost its noise

over a more ample bed. Its speed was quenched, in the same manner

Comments (0)