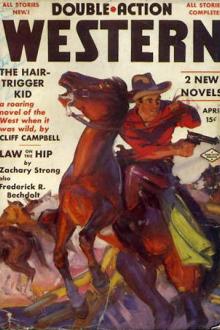

The Hair-Trigger Kid - Max Brand (uplifting novels .TXT) 📗

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid - Max Brand (uplifting novels .TXT) 📗». Author Max Brand

moment, for a final reef of rocks in the neck of the canyon had chopped

up the waters and taken their headway from them.

Now, all in a moment, the water slackened and spread out shallowly across

a bed four times as spacious as that into which it had been crowded by

the narrow walls of the ravine. Here, flat-faced, gently, it ran into the

open valley, heading toward the other dark throat into which it was soon

to fall and again begin to rage and roar like a lion.

And the Kid, soaked to the skin, tired, and aching from his labors,

looked out on that flow of water as a strong and busy man looks out upon

one placid moment between strenuous days of action and of danger—one

walk through the green country, one solemn moment of peace.

Yet there was no peace for him.

He had performed all of these labors merely to bring himself to the door

which opened upon the real peril. And of all the arduous tasks which he

had taken in hand in his days, none was comparable with the thing which

lay before him.

No strength or craft of hand, he knew, could ever make him equal to the

assembled strength which Dixon had gathered here.

If he were superior to each of them by the flickering, broken part of a

second in speed of draw; if he were a finger’s breadth closer to the

bull’s-eye when he fired, these advantages which meant life and victory

in a single combat were nothing compared with the overwhelming odds which

he would have to encounter.

No, there was now nothing left for him except subtlety and silent craft,

like an adventuring Indian in a camp of the enemy.

The Kid, taking stock of these truths, gravely advanced still farther,

until he was on the exact verge of the canyon mouth, where a little shore

of gravel went down to the waters.

From this point, he could see all that the hollow contained. He could see

the mist rising faintly against the stars above the uneasy cattle. He

could hear the desperate moaning voices of the thirst-starved creatures.

That sound made the roar of the river at once a small thing.

He looked down on the red beacon of the camp fire where his enemies were.

He looked away to either side, where the soft curves of the hills

undulated against the sky line; surely those hills never had seen a

stranger thing than he would attempt this night!

Then, narrowing his eyes, he crouched low, his head close to the water,

and scanned the shore on each side.

He was inside the lines, He could see, here and there, the flicker of the

barbed wire which made the outer defense. He could see also the

occasional form of a guard marching as a sentinel up and down the fences.

Now, as he watched, he saw the vague outline of a man come from the camp

fire and walk down to the water’s edge. There the fellow stood. It was

Dixon, perhaps rejoicing in the mischief which he was working, and

grinning as he listened to the noise of the tormented cattle.

His own mind flashed back to another picture—the sunwhitened desert, and

the two poor cows struggling and swaying under their unaccustomed yokes.

Then he stepped with his naked feet into the cold waters of the stream.

His revolver he kept above the surface of the stream, which was now not

more than three or four feet deep. But though it was shallow, and slid

along a fairly fiat surface, there was amazing force in it still, the

last effect of the long impetus which it had received in shooting down

the flume of the ravine.

He had to lean upstream at a sharp angle, with the current heaping

shoulder and even neck high as it bubbled and rushed and gurgled loudly.

His nerves were as good as those of any man, but before he was halfway

across the stream, walking in the dim, red path of the light from the

camp fire, he made certain that the men on the shore must have seen him.

If they had not seen, they must have heard. Surely they were watching

there, laughing in the dark of the covert, and grinning at the poor fool

who was walking into their hands.

Then he remembered that there were other noises abroad in the valley

besides the intimate voice of the river just under his ear. There was the

dull and distant roaring of the penned-up waters in the canyon above, and

a deeper, fainter call from the lower ravine; above all, the solemn music

of the lowing cattle flooded across the hollow.

No, he could not be heard, but surely he was seen!

The long, red arm of the firelight stretched toward him and caught him by

the throat.

He thought of lying flat on the surface of the stream. It would shoot him

like a log safe past the fire, past all the watchers, and at the mouth of

the lower canyon, he would struggle on shore and try to escape.

That thought of flight tempted him mightily. He fairly trembled on the

verge of giving way to it.

But he went on.

The strength of the resolve which drove him had a pull like that of

gravity and carried him step by step against his reason. And then the

ground was shoaling beneath him. The suction grew less in the shallows,

and finally he crawled out on his hands and knees.

There on the shore he lay flat.

He was shuddering with cold. He was helpless with it. Any yokel, any

cowardly boy might have mastered him then, he felt. The snow water had

sent its numbing chill through him to the bone. His breathing failed. The

tremors shook him more than earthquakes shake cities.

But he had to lie quietly while he took stock of the situation before

him.

He was not nearly as close to the camp fire as he had thought while

striding across the creek. He lay, in fact, some distance to the north of

it, and between him and the flames stood a row of three wagons. Their

wheels looked enormous and misshapen. They seemed to be broken and

flattened on the lower surface that met the ground. Their shadows went

wavering across the ground. Sometimes it was as though the wheels were

turning.

Around the fire three or four men were sitting.

Others, wrapped in their blankets, apparently were asleep, or trying to

sleep. And it seemed to the Kid that this was the ultimate proof of their

brutality. They could sleep while that sound of agony from the thirsty

cattle moaned and howled across the valley! That water which had tugged

at him which had swept by him in countless barrelfuls, in unnumerable

tones, which had frozen and shaken him, how sweet it would have been in

the dusty, dry gullets of those thousands and thousands of dying beasts.

All the sweetness of life would have been in it.

A blast of heat came to him out of memory as he thought again of the

unforgotten picture of his boyhood—the creaking wagon, and the two old

cows swaying and staggering before it, halting in their steps, but

leaning again on the yoke and slowly drifting the miles behind them. He

himself had had the thirst of fever in his body on that day. He had it

again now. A flash of burning heat, and of hatred for these men or devils

who were with Dixon.

When he looked more closely toward the fire, he saw that on the opposite

side, with the full red flush of the flame in his face, sat Dixon

himself, looking rather old and stoop-shouldered, as almost any man will,

who is sitting cross-legged on the ground.

Suppose that Dixon guessed, even faintly dreamed, that his enemy had

broken through the invincible outer lines and was lying there in easy

gunshot? Oh, so easy to draw a bead even from this distance, and by

pressing the trigger, beckon the brain and heart of the enterprise out of

existence!

He could not do it.

His philosophy, blunt and uncertain on many points of life, was in one

respect absolute and true. He could not strike from behind or from the

dark. There was no Indian in his nature to excuse such ways of fighting.

But he felt, at the sight of Dixon, a calm heat of anger rise that made

him forget the river water and its cold hands.

He got up to his knees and went slowly on, still pausing to turn his head

from time to time, until he reached a thick, solid wedge of shadow that

extended behind one of the wagons.

When he came to this, he rose, and as he rose, he saw suddenly that a man

was standing before him!

The breath was pressed from him by that sight. His mind spun about. It

was as though a spirit had risen through and out of the solid ground.

How long had the man been there, lost in the shadow, calmly watching the

progress of the spy, the secret enemy? Who was he that he dared to take

that advance so calmly?

These questions rushed through the mind of the Kid in a broken portion of

a second.

“Where’d you get the redeye that knocked you out, buddy?” said the man.

“You know where you been? You been crawlin’ around, this side of the

water, like a sick snake! Did Bolony Joe open up that keg of his for you,

or d’you tap it for yourself? Old Champ will sure raise a riot if he

finds out. You better not let him see you!”

“You’re a fool,” snarled the Kid in apparent anger. “I got a slip and

fall down there on the edge of the water, and I got soaked, and turned my

ankle. The ligaments are ‘bout pulled out of place. Get out of the way,

will you, and leave me be with your fool ideas!”

“Who are you?” demanded the other, taking a step closer. “Who are you to

be orderin’ me around? I’ll tel! you a thing or two, old son, if you was

ten Champ Dixons rolled into one!”

He came closer. The Kid was silent, but putting down his right foot on

the ground, he made a slow, hobbling step, and groaned aloud.

The other was not moved. He had come much closer.

“Yeah. You come out of the river, all right,” said he, “but I dunno that

I recognize you. What’s your moniker, son? I don’t seem to place your

head and shoulders, sort of, among the boys. What’s your name?”

“I’m the Kid,” said he.

This name made the man jump back a good yard in surprise and in fear.

Then he began to laugh. He laughed with deep enjoyment. “Yeah, you’re the

Kid, are you?”

“I’m the Kid,” said he truthfully.

“I didn’t know you, Larry,” said the other. “I wouldn’t never of guessed

you, except you begun kidding, like that. It’s a funny thing the way

night changes things. Your voice is changed too.”

“How could it help?” said the Kid, “and me doused in that ice water and

pneumonia likely, coming on!”

“Here,” said the other. “I’ll give you a hand back to your blankets.

Where’d you bed down? Over by the fire, or in one of the wagons?”

“Leave me be,” said the Kid.

Comments (0)