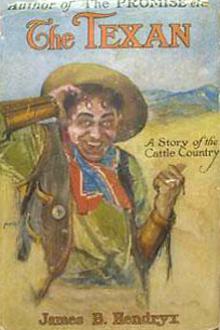

The Texan - James B. Hendryx (best historical fiction books of all time txt) 📗

- Author: James B. Hendryx

- Performer: -

Book online «The Texan - James B. Hendryx (best historical fiction books of all time txt) 📗». Author James B. Hendryx

"We don't draw no flour, nor rice, not jerky, anyhow," said the puncher, examining the bags. "Nor bacon, either. The only chance we stand to make a haul is on the air-tights."

"What are air-tights?" asked the girl.

"Canned stuff—tomatoes are the best for this kind of weather—keep you from gettin' thirsty. I've be'n in this country long enough to pretty much know its habits, but I never saw it this hot in June."

"She feel lak' dat dam' Yuma bench, but here is only de rattlesnake. We don' got to all de tam hont de pizen boog. Dat ain' no good for git so dam' hot—she burn' oop de range. If it ain' so mooch danger for Win to git hang—" He paused and looked at Tex with owlish solemnity. "A'm no lak we cross dem bad lands. Better A'm lak we gon' back t'rough de mountaine."

"You dig out them air-tights, if there's any in there, an' quit your croakin'!" ordered the cowboy.

And with a grin Bat thrust in his arm to the shoulder. One by one he drew out the tins—eight in all, and laid them in a row. The labels had disappeared and the Texan stood looking down at them.

"Anyway we have these," smiled the girl, but the cowboy shook his head.

"Those big ones are tomatoes, an' the others are corn, an' peas—but, it don't make any difference." He pointed to the cans in disgust: "See those ends bulged out that way? If we'd eat any of the stuff in those cans we'd curl up an' die, pronto. Roll 'em back, Bat, we got grub enough without 'em. Two days will put us through the bad lands an' we've got plenty. We'll start when the moon comes up."

All four spent the afternoon in the meagre shade of the bull pine, seeking some amelioration from the awful scorching heat. But it was scant protection they got, and no comfort. The merciless rays of the sun beat down upon the little plateau, heating the rocks to a degree that rendered them intolerable to the touch. No breath of air stirred. The horses ceased to graze and stood in the scrub with lowered heads and wide-spread legs, sweating.

Towards evening a breeze sprang up from the southeast, but it was a breeze that brought with it no atom of comfort. It blew hot and stifling like the scorching blast of some mighty furnace. For an hour after the sun went down in a glow of red the super-heated rocks continued to give off their heat and the wind swept, sirocco-like, over the little camp. Before the after-glow had faded from the sky the wind died and a delicious coolness pervaded the plateau.

"It hardly seems possible," said Alice, as she breathed deeply of the vivifying air, "that in this very spot only a few hours ago we were gasping for breath.

"You can always bank on the nights bein' cold," answered Tex, as he proceeded to build the fire. "We'll rustle around and get supper out of the way an' the outfit packed an' we can pull our freight as soon as it's light enough. The moon ought to show up by half-past ten or eleven, an' we can make the split rock water-hole before it gets too hot for the horses to travel. It's the hottest spell for June I ever saw and if she don't let up tomorrow the range will be burnt to a frazzle."

Bat cast a weather-wise eye toward the sky which, cloudless, nevertheless seemed filmed with a peculiar haze that obscured the million lesser stars and distorted the greater ones, so that they showed sullen and angry and dull like the malignant pustules of a diseased skin.

"A'm t'ink she gon' for bus' loose pret' queek."

"Another thunder storm and a deluge of rain?" asked Alice.

The half-breed shrugged: "I ain' know mooch 'bout dat. I ain' t'ink she feel lak de rain. She ain' feel good."

"Leave off croakin', Bat, an' get to work an' pack," growled the Texan.

"There'll be plenty time to gloom about the weather when it gets here."

An hour later the outfit was ready for the trail.

"Wish we had one of them African water-bags," said the cowboy, as he filled his flask at the spring. "But I guess this will do 'til we strike the water-hole."

"Where is that whiskey bottle?" asked Endicott. "We could take a chance on snake-bite, dump out the booze, and use the bottle for water."

The Texan shook his head: "I had bad luck with that bottle; it knocked against a rock an' got busted. So we've got to lump the snake-bite with the thirst, an' take a chance on both of 'em."

"How far is the water-hole?" Alice asked, as she eyed the flask that the cowboy was making fast in his slicker.

"About forty miles, I reckon. We've got this, and three cans of tomatoes, but we want to go easy on 'em, because there's a good ride ahead of us after we hit Split Rock, an' that's the only water, except poison springs, between here an' the old Miszoo."

Bat, who had come up with the horses, pointed gloomily at the moon which had just topped the shoulder of a mountain. "She all squash down. Dat ain' no good she look so red." The others followed his gaze, and for a moment all stared at the distorted crimson oblong that hung low above the mountains. A peculiar dull luminosity radiated from the misshapen orb and bathed the bad lands in a flood of weird murky light.

"Come on," cried Tex, swinging into his saddle, "we'll hit the trail before this old Python here finds something else to forebode about. For all I care the moon can turn green, an' grow a hump like a camel just so she gives us light enough to see by." He led the way across the little plateau and the others followed. With eyes tight-shut and hands gripping the saddle-horn, Alice gave her horse full rein as he followed the Texan's down the narrow sloping ledge that answered for a trail. Nor did she open her eyes until the reassuring voice of the cowboy told her the danger was past.

Tex led the way around the base of the butte and down into the coulee he had followed the previous day. "We've got to take it easy this trip," he explained. "There ain't any too much light an' we can't take any chances on holes an' loose rocks. It'll be rough goin' all the way, but a good fast walk ought to put us half way, by daylight, an' then we can hit her up a little better." The moon swung higher and the light increased somewhat, but at best it was poor enough, serving only to bring out the general outlines of the trail and the bolder contour of the coulee's rim. No breath of the wind stirred the air that was cold, with a dank, clammy coldness—like the dead air of a cistern. As she rode, the girl noticed the absence of its buoyant tang. The horses' hoofs rang hollow and thin on the hard rock of the coulee bed, and even the frenzied yapping of a pack of coyotes, sounded uncanny and far away. Between these sounds the stillness seemed oppressive—charged with a nameless feeling of unwholesome portent. "It is the evil spell of the bad lands," thought the girl, and shuddered.

Dawn broke with the moon still high above the western skyline. The sides of the coulee had flattened and they traversed a country of low-lying ridges and undulating rock-basins. As the yellow rim of the sun showed above the crest of a far-off ridge, their ears caught the muffled roar of wind. From the elevation of a low hill the four gazed toward the west where a low-hung dust-cloud, lowering, ominous, mounted higher and higher as the roar of the wind increased. The air about them remained motionless—dead. Suddenly it trembled, swirled, and rushed forward to meet the oncoming dust-cloud as though drawn toward it by the suck of a mighty vortex.

"Dat better we gon' for hont de hole. Dat dust sto'm she raise hell."

"Hole up, nothin'!" cried the Texan; "How are we goin' to hole up—four of us an' five horses, on a pint of water an' three cans of tomatoes? When that storm hits it's goin' to be hot. We've just naturally got to make that water-hole! Come on, ride like the devil before she hits, because we're goin' to slack up considerable, directly."

The cowboy led the way and the others followed, urging their horses at top speed. The air was still cool, and as she rode, Alice glanced over her shoulder toward the dust cloud, nearer now, by many miles. The roar of the wind increased in volume. "It's like the roar of the falls at Niagara," she thought, and spurred her horse close beside the Texan's.

"Only seventeen or eighteen miles," she heard him say, as her horse drew abreast. "The wind's almost at our back, an' that'll help some." He jerked the silk scarf from his neck and extended it toward her. "Cover your mouth an' nose with that when she hits. An' keep your eyes shut. We'll make it all right, but it's goin' to be tough." A mile further on the storm burst with the fury of a hurricane. The wind roared down upon them like a blast from hell. Daylight blotted out, and where a moment before the sun had hung like a burnished brazen shield, was only a dim lightening of the impenetrable fog of grey-black dust. The girl opened her eyes and instantly they seemed filled with a thousand needles that bit and seared and caused hot stinging tears to well between the tight-closed lids. She gasped for breath and her lips and tongue went dry. Sand gritted against her teeth as she closed them, and she tried in vain to spit the dust from her mouth. She was aware that someone was tying the scarf about her head, and close against her ear she heard the voice of the Texan: "Breathe through your nose as long as you can an' then through your teeth. Hang onto your saddle-horn, I've got your reins. An' whatever you do, keep your eyes shut, this sand will cut 'em out if you don't." She turned her face for an instant toward the west, and the sand particles drove against her exposed forehead and eyelids with a force that caused the stinging tears to flow afresh. Then she felt her horse move slowly, jerkily at first, then more easily as the Texan swung him in beside his own.

"We're all right now," he shouted at the top of his lungs to make himself heard above the roar of the wind. And then it seemed to the girl they rode on and on for hours without a spoken word. She came to tell by the force of the wind whether they travelled along ridges, or wide low basins, or narrow coulees. Her lips dried and cracked, and the fine dust and sand particles were driven beneath her clothing until her skin smarted and chafed under their gritty torture. Suddenly the wind seemed to die down and the horses stopped. She heard the Texan swing to the ground at her side, and she tried to open her eyes but they were glued fast. She endeavoured to speak and found the effort a torture because of the thick crusting of alkali dust and sand that tore at her broken lips. The scarf was loosened and allowed to fall about her neck. She could hear the others dismounting and the loud sounds with which the horses strove to rid their nostrils of the crusted grime.

"Just a minute, now, an' you can open your eyes," the Texan's words fell with a dry rasp of his tongue upon his caked lips. She heard a slight splashing sound and the next moment the grateful feel of water was upon her burning eyelids, as the Texan sponged at them with a saturated bit of cloth.

"The water-hole!" she managed to gasp.

"There's water here," answered the cowboy,

Comments (0)