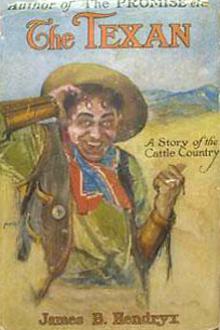

The Texan - James B. Hendryx (best historical fiction books of all time txt) 📗

- Author: James B. Hendryx

- Performer: -

Book online «The Texan - James B. Hendryx (best historical fiction books of all time txt) 📗». Author James B. Hendryx

The Texan shook his head: "I got you into this deal, an'——"

"You did it to protect me!" flared Endicott. "I'm the cause for all this, and I'll stand the gaff!"

The Texan smiled, and Endicott noticed that it was the same cynical smile with which the man had regarded him in the dance hall, and again as they had faced each other under the cottonwoods of Buffalo Coulee. "Since when you be'n runnin' this outfit?"

"It don't make any difference since when! The fact is, I'm running it, now—that is, to the extent that I'll be damned if you're going to stay behind and rot in this God-forsaken inferno, while I ride to safety on your horse."

The smile died from the cowboy's face: "It ain't that, Win. I guess you don't savvy, but I do. She's yours, man. Take her an' go! There was a while that I thought—but, hell!"

"I'm not so sure of that," Endicott replied. "Only yesterday, or the day before, she told me she could not choose—yet."

"She'll choose," answered Tex, "an' she won't choose—me. She ain't makin' no mistake, neither. By God, I know a man when I see one!"

Endicott stepped forward and shook his fist in the cowboy's face: "It's the only chance. You can do it—I can't. For God's sake, man, be sensible! Either of us would do it—for her. It is only a question of success, and all that it means; and failure—and all that that means. You know the country—I don't. You are experienced in fighting this damned desert—I'm not. Any one of a dozen things might mean the difference between life and death. You would take advantage of them—I couldn't."

"You're a lawyer, Win—an' a damn good one. I wondered what your trade was. If I ever run foul of the law, I'll sure send for you, pronto. If I was a jury you'd have me plumb convinced—but, I ain't a jury. The way I look at it, the case stands about like this: We can't stay here, and there can't only two of us go. I can hold out here longer than you could, an' you can go just as far with the horses as I could. Just give them their head an' let them drift—that's all I could do. If the storm lets up you'll see the Split Rock water-hole—you can't miss it if you're in sight of it, there's a long black ridge with a big busted rock on the end of it, an' just off the end is a round, high mound—the soda hill, they call it, and the water-hole is between. If you pass the water-hole, you'll strike the Miszoo. You can tell that from a long ways off, too, by the fringe of green that lines the banks. And, as for the rest of it—I mean, if the storm don't let up, or the horses go down, I couldn't do any more than you could—it's cashin' in time then anyhow, an' the long, long sleep, no matter who's runnin' the outfit. An' if it comes to that, it's better for her to pass her last hours with one of her own kind than with—me."

Endicott thrust out his hand: "I think any one could be proud to spend their last hours with one of your kind," he said huskily. "I believe we will all win through—but, if worse comes to worst—— Good Bye."

"So Long, Win," said the cowboy, grasping the hand. "Wake her up an' pull out quick. I'll onhobble the horses."

CHAPTER XVIII "WIN"Alice opened her eyes to see Endicott bending over her. "It is time to pull out," said the man tersely.

The girl threw off the blanket and stared into the whirl of opaque dust. "The storm is still raging," she murmured. "Oh, Winthrop, do you know that I dreamed it was all over—that we were riding between high, cool mountains beside a flashing stream. And trout were leaping in the rapids, and I got off and drank and drank of the clear, cold water, and, why, do you know, I feel actually refreshed! The horrible burning thirst has gone. That proves the control mind has over matter—if we could just concentrate and think hard enough, I don't believe we would ever need to be thirsty, or hungry, or tired, or cold, do you?"

The man smiled grimly, and shook his head: "No. If we could think hard enough to accomplish a thing, why, manifestly that thing would be accomplished. Great word—enough—the trouble is, when you use it, you never say anything."

Alice laughed: "You're making fun of me. I don't care, you know what I mean, anyway. Why, what's the matter with that horse?"

"He died—got weaker and weaker, and at last he just rolled over dead. And that is why we have to hurry and make a try for the water-hole, before the others play out."

Endicott noticed that the Texan was nowhere in sight. He pressed his lips firmly: "It's better that way, I guess," he thought.

"But, that's your horse! And where are the others—Tex, and Bat, and the pack-horse?"

"They pulled out to hunt for the water-hole—each in a different direction. You and I are to keep together and drift with the wind as we have been doing."

"And they gave us the best of it," she breathed. Endicott winced, and the girl noticed. She laid her hand gently upon his arm. "No, Winthrop, I didn't mean that. There was a time, perhaps, when I might have thought—but, that was before I knew you. I have learned a lot in the past few days, Winthrop—enough to know that no matter what happens, you have played a man's part—with the rest of them. Come, I'm ready."

Endicott tied the scarf about her face and assisted her to mount, then, throwing her bridle reins over the horn of his saddle as the Texan had done, he headed down the coulee. For three hours the horses drifted with the storm, following along coulees, crossing low ridges, and long level stretches where the sweep of the wind seemed at times as though it would tear them from the saddles. Endicott's horse stumbled frequently, and each time the recovery seemed more and more of an effort. Then suddenly the wind died—ceased to blow as abruptly as it had started. The man could scarcely believe his senses as he listened in vain for the roar of it—the steady, sullen roar, that had rung in his ears, it seemed, since the beginning of time. Thick dust filled the air but when he turned his face toward the west no sand particles stung his skin. Through a rift he caught sight of a low butte—a butte that was not nearby. Alice tore the scarf from her face. "It has stopped!" she cried, excitedly. "The storm is over!"

"Thank God!" breathed Endicott, "the dust is beginning to settle." He dismounted and swung the girl to the ground. "We may as well wait here as anywhere until the air clears sufficiently for us to get our bearings. We certainly must have passed the water-hole, and we would only be going farther and farther away if we pushed on."

The dust settled rapidly. Splashes of sunshine showed here and there upon the basin and ridge, and it grew lighter. The atmosphere took on the appearance of a thin grey fog that momentarily grew thinner. Endicott walked to the top of a low mound and gazed eagerly about him. Distant objects were beginning to appear—bare rock-ridges, and low-lying hills, and deep coulees. In vain the man's eyes followed the ridges for one that terminated in a huge broken rock, with its nearby soda hill. No such ridge appeared, and no high, round hill. Suddenly his gaze became rivetted upon the southern horizon. What was that stretching away, long, and dark, and winding? Surely—surely it was—trees! Again and again he tried to focus his gaze upon that long dark line, but always his lids drew over his stinging eyeballs, and with a half-sobbed curse, he dashed the water from his eyes. At last he saw it—the green of distant timber. "The Missouri—five miles—maybe more. Oh God, if the horses hold out!" Running, stumbling, he made his way to the girl's side. "It's the river!" he cried. "The Missouri!"

"Look at the horses!" she exclaimed. "They see it, too!" The animals stood with ears cocked forward, and dirt-caked nostrils distended, gazing into the south. Endicott sprang to his slicker, and producing the flask, saturated his handkerchief with the thick red liquid. He tried to sponge out the mouths and noses of the horses but they drew back, trembling and snorting in terror.

"Why, it's blood!" cried the girl, her eyes dilated with horror. "From the horse that died," explained Endicott, as he tossed the rag to the ground.

"But, the water—surely there was water in the flask last night!" Then, of a sudden, she understood. "You—you fed it to me in my sleep," she faltered. "You were afraid I would refuse, and that was my dream!"

"Mind over matter," reminded Endicott, with a distortion of his bleeding lips that passed for a grin. Again he fumbled in his slicker and withdrew the untouched can of tomatoes. He cut its cover as he had seen Tex do and extended it to the girl. "Drink some of this, and if the horses hold out we will reach the river in a couple of hours."

"I believe it's growing a little cooler since that awful wind went down," she said, as she passed the can back to Endicott. "Let's push on, the horses seem to know there is water ahead. Oh, I hope they can make it!"

"We can go on a-foot if they can't," reassured the man. "It is not far."

The horses pushed on with renewed life. They stumbled weakly, but the hopeless, lack-lustre look was gone from their eyes and at frequent intervals they stretched their quivering nostrils toward the long green line in the distance. So slow was their laboured pace that at the end of a half-hour Endicott dismounted and walked, hobbling clumsily over the hot rocks and through ankle-deep drifts of dust in his high-heeled boots. A buzzard rose from the coulee ahead with silent flapping of wings, to be joined a moment later by two more of his evil ilk, and the three wheeled in wide circles above the spot from which they had been frightened. A bend in the coulee revealed a stagnant poison spring. A dead horse lay beside it with his head buried to the ears in the slimy water. Alice glanced at the broken chain of the hobbles that still encircled the horse's feet.

"It's the pack-horse!" she cried. "They have only one horse between them!"

"Yes, he got away in the night." Endicott nodded. "Bat is hunting water, and Tex is waiting." He carried water in his hat and dashed it over the heads of the horses, and sponged out their mouths and noses as Tex and Bat had done. The drooping animals revived wonderfully under the treatment and, with the long green line of scrub timber now plainly in sight, evinced an eagerness for the trail that, since the departure from Antelope Butte, had been entirely wanting. As the man assisted the girl to mount, he saw that she was crying.

"They'll come out, all right," he assured her. "As soon as we hit the river and I can get a fresh horse, I'm going back."

"Going back!"

"Going back, of course—with water. You do not expect me to leave them?"

"No, I don't expect you to leave them! Oh, Winthrop, I—" her voice choked up and the sentence was never finished.

"Buck up, little girl, an

Comments (0)