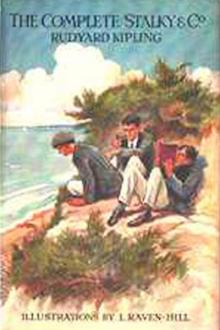

Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗

- Author: Rudyard Kipling

- Performer: -

Book online «Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗». Author Rudyard Kipling

They crawled out, brushed one another clean, slid the saloon-pistols down a trouser-leg, and hurried forth to a deep and solitary Devonshire lane in whose flanks a boy might sometimes slay a young rabbit. They threw themselves down under the rank elder bushes, and began to think aloud.

“You know,” said Stalky at last, sighting at a distant sparrow, “we could hide our sallies in there like anything.”

“Huh!” Beetle snorted, choked, and gurgled. He had been silent since they left the dormitory. “Did you ever read a book called ‘The History of a House’ or something? I got it out of the library the other day. A French woman wrote it—Violet somebody. But it’s translated, you know; and it’s very interestin’. Tells you how a house is built.”

“Well, if you’re in a sweat to find out that, you can go down to the new cottages they’re building for the coastguard.”

“My Hat! I will.” He felt in his pockets. “Give me tuppence, some one.”

“Rot! Stay here, and don’t mess about in the sun.”

“Gi’ me tuppence.”

“I say, Beetle, you aren’t stuffy about anything, are you?” said McTurk, handing over the coppers. His tone was serious, for though Stalky often, and McTurk occasionally, manoeuvred on his own account, Beetle had never been known to do so in all the history of the confederacy.

“No, I’m not. I’m thinking.”

“Well, we’ll come, too,” said Stalky, with a general’s suspicion of his aides.

“Don’t want you.”

“Oh, leave him alone. He’s been taken worse with a poem,” said McTurk. “He’ll go burbling down to the Pebbleridge and spit it all up in the study when he comes back.”

“Then why did he want the tuppence, Turkey? He’s gettin’ too beastly independent. Hi! There’s a bunny. No, it ain’t. It’s a cat, by Jove! You plug first.”

Twenty minutes later a boy with a straw hat at the back of his head, and his hands in his pockets, was staring at workmen as they moved about a half-finished cottage. He produced some ferocious tobacco, and was passed from the forecourt into the interior, where he asked many questions.

“Well, let’s have your beastly epic,” said Turkey, as they burst into the study, to find Beetle deep in Viollet-le-Duc and some drawings. “We’ve had no end of a lark.”

“Epic? What epic? I’ve been down to the coastguard.”

“No epic? Then we will slay you, O Beetle,” said Stalky, moving to the attack. “You’ve got something up your sleeve. I know, when you talk in that tone!”

“Your Uncle Beetle”—with an attempt to imitate Stalky’s war-voice—“is a great man.”

“Oh, no; he jolly well isn’t anything of the kind. You deceive yourself, Beetle. Scrag him, Turkey!”

“A great man,” Beetle gurgled from the floor. “You are futile—look out for my tie!—futile burblers. I am the Great Man. I gloat. Ouch! Hear me!”

“Beetle, de-ah”—Stalky dropped unreservedly on Beetle’s chest—” we love you, an’ you’re a poet. If I ever said you were a doggaroo, I apologize; but you know as well as we do that you can’t do anything by yourself without mucking it.”

“I’ve got a notion.”

“And you’ll spoil the whole show if you don’t tell your Uncle Stalky. Cough it up, ducky, and we’ll see what we can do. Notion, you fat impostor—I knew you had a notion when you went away! Turkey said it was a poem.”

“I’ve found out how houses are built. Le’ me get up. The floor-joists of one room are the ceiling-joists of the room below.”

“Don’t be so filthy technical.”

“Well, the man told me. The floor is laid on top of those joists—those boards on edge that we crawled over—but the floor stops at a partition. Well, if you get behind a partition, same as you did in the attic, don’t you see that you can shove anything you please under the floor between the floor-boards and the lath and plaster of the ceiling below? Look here. I’ve drawn it.”

He produced a rude sketch, sufficient to enlighten the allies. There is no part of the modern school curriculum that deals with architecture, and none of them had yet reflected whether floors and ceilings were hollow or solid. Outside his own immediate interests the boy is as ignorant as the savage he so admires; but he has also the savage’s resource.

“I see,” said Stalky. “I shoved my hand there. An’ then?”

“An’ then They’ve been calling us stinkers, you know. We might shove somethin’ under—sulphur, or something that stunk pretty bad—an’ stink ‘em out. I know it can be done somehow.” Beetle’s eyes turned to Stalky handling the diagrams.

“Stinks?” said Stalky interrogatively. Then his face grew luminous with delight. “By gum! I’ve got it. Horrid stinks! Turkey!” He leaped at the Irishman. “This afternoon—just after Beetle went away! She’s the very thing!”

“Come to my arms, my beamish boy,” caroled McTurk, and they fell into each other’s arms dancing. “Oh, frabjous day! Calloo, callay! She will! She will!”

“Hold on,” said Beetle. “I don’t understand.”

“Dearr man! It shall, though. Oh, Artie, my pure-souled youth, let us tell our darling Reggie about Pestiferous Stinkadores.”

“Not until after callover. Come on!”

“I say,” said Orrin, stiffly, as they fell into their places along the walls of the gymnasium. “The house are goin’ to hold another meeting.”

“Hold away, then.” Stalky’s mind was elsewhere.

“It’s about you three this time.”

“All right, give ‘em my love… Here,sir_,” and he tore down the corridor.

Gamboling like kids at play, with bounds and sidestarts, with caperings and curvetings, they led the almost bursting Beetle to the rabbit-lane, and from under a pile of stones drew forth the new-slain corpse of a cat. Then did Beetle see the inner meaning of what had gone before, and lifted up his voice in thanksgiving for that the world held warriors so wise as Stalky and McTurk.

“Well-nourished old lady, ain’t she?” said Stalky. “How long d’you suppose it’ll take her to get a bit whiff in a confined space?”

“Bit whiff! What a coarse brute you are!” said McTurk. “Can’t a poor pussy-cat get under King’s dormitory floor to die without your pursuin’ her with your foul innuendoes?”

“What did she die under the floor for?’ said Beetle, looking to the future.

“Oh, they won’t worry about that when they find her,” said Stalky.

“A cat may look at a king.” McTurk rolled down the bank at his own jest. “Pussy, you don’t know how useful you’re goin’ to be to three pure-souled, high-minded boys.”

“They’ll have to take up the floor for her, same as they did in Number Nine when the rat croaked. Big medicine—heap big medicine! Phew! Oh, Lord, I wish I could stop laughin’,” said Beetle.

“Stinks! Hi, stinks! Clammy ones!” McTurk gasped as he regained his place. “And”—the exquisite humor of it brought them sliding down together in a tangle—“it’s all for the honor of the house, too!”

“An’ they’re holdin’ another meeting—on us,” Stalky panted, his knees in the ditch and his face in the long grass. “Well, let’s get the bullet out of her and hurry up. The sooner she’s bedded out the better.”

Between them they did some grisly work with a penknife; between them (ask not who buttoned her to his bosom) they took up the corpse and hastened back, Stalky arranging their plan of action at the full trot.

The afternoon sun, lying in broad patches on the bed-rugs, saw three boys and an umbrella disappear into a dormitory wall. In five minutes they emerged, brushed themselves all over, washed their hands, combed their hair, and descended.

“Are you sure you shoved her far enough under?” said McTurk suddenly.

“Hang it, man, I shoved her the full length of my arm and Beetle’s brolly. That must be about six feet. She’s bung in the middle of King’s big upper ten-bedder. Eligible central situation, I call it. She’ll stink out his chaps, and Hartopp’s and Macrea’s, when she really begins to fume. I swear your Uncle Stalky is a great man. Do you realize what a great man he is, Beetle?”

“Well, I had the notion first, hadn’t I—? only—”

“You couldn’t do it without your Uncle Stalky, could you?”

“They’ve been calling us stinkers for a week now,” said McTurk. “Oh, won’t they catch it!”

“Stinker! Yah! Stink-ah!” rang down the corridor.

“And she’s there,” said Stalky, a hand on either boy’s shoulder. “She—is—there, gettin’ ready to surprise ‘em. Presently she’ll begin to whisper to ‘em in their dreams. Then she’ll whiff. Golly, how she’ll whiff! Oblige me by thinkin’ of it for two minutes.”

They went to their study in more or less of silence. There they began to laugh—laugh as only boys can. They laughed with their foreheads on the tables, or on the floor; laughed at length, curled over the backs of chairs or clinging to a bookshelf; laughed themselves limp.

And in the middle of it Orrin entered on behalf of the house. “Don’t mind us, Orrin; sit down. You don’t know how we respect and admire you. There’s something about your pure, high young forehead, full of the dreams of innocent boyhood, that’s no end fetchin’. It is, indeed.”

“The house sent me to give you this.” He laid a folded sheet of paper on the table and retired with an awful front.

“It’s the resolution! Oh, read it, some one. I’m too silly-sick with laughin’ to see,” said Beetle. Stalky jerked it open with a precautionary sniff. “Phew! Phew! Listen. ‘Thehouse_noticeswithpainandcontempttheattitudeofindiference_’ —how many f’s in indifference, Beetle?”

“Two for choice.”

“Only one here—’adoptedbytheoccupantsofNumber_Five_studyin relation_totheinsults_offered_to_Mr._Prout’s_house_attherecent_ meetinginNumber_Twelve_form-room,andthe_House_hereby_passa voteofcensure_onthesaid_study._ That’s all.”

“And she bled all down my shirt, too!” said Beetle.

“An’ I’m catty all over,” said McTurk, “though I washed twice.”

“An’ I nearly broke Beetle’s brolly plantin’ her where she would blossom!”

The situation was beyond speech, but not laughter. There was some attempt that night to demonstrate against the three in their dormitory; so they came forth.

“You see,” Beetle began suavely as he loosened his braces, “the trouble with you is that you’re a set of unthinkin’ asses. You’ve no more brains than spidgers. We’ve told you that heaps of times, haven’t we.?”

“We’ll give the three of you a dormitory lickin’. You always jaw at us as if you were prefects,” cried one.

“Oh, no, you won’t,” said Stalky, “because you know that if you did you’d get the worst of it sooner or later. We aren’t in any hurry. We can afford to wait for our little revenges. You’ve made howlin’ asses of yourselves, and just as soon as King gets hold of your precious resolutions to-morrow you’ll find that out. If you aren’t sick an’ sorry by to-morrow night, I’ll—I’ll eat my hat.”

But or ever the dinner-bell rang the next day Prout’s were sadly aware of their error. King received stray members of that house with an exaggerated attitude of fear. Did they purpose to cause him to be dismissed from the College by unanimous resolution? What were their views concerning the government of the school, that he might hasten to give effect to them? he would not offend them for worlds; but he feared—he sadly feared—that his own house, who did not pass resolutions (but washed), might somewhat deride.

King was a happy man, and his house, basking in the favor of his smile, made that afternoon a long penance to the misled Prouts. And Prout himself, with a dull and lowering visage, tried to think out the rights and wrongs of it all, only plunging deeper into bewilderment. Why should his house be called “Stinkers”? Truly, it was a small thing, but he had been trained to believe

Comments (0)