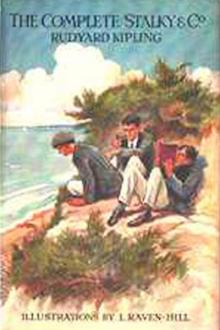

Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗

- Author: Rudyard Kipling

- Performer: -

Book online «Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗». Author Rudyard Kipling

“Poor chap!” said Beetle, with a false, feigned sympathy. “Let it bleed a little. That’ll prevent apoplexy,” and he held the blind head skilfully over the table, and the papers on the table, as he guided the howling Manders to the door.

Then did Beetle, alone with the wreckage, return good for evil. How, in that office, a complete set of “Gibbon” was scarred all along the back as by a flint; how so much black and copying ink came to be mingled with Manders’s gore on the table-cloth; why the big gum-bottle, unstoppered, had rolled semicircularly across the floor; and in what manner the white china door-knob grew to be painted with yet more of Manders’s young blood, were matters which Beetle did not explain when the rabid King returned to find him standing politely over the reeking hearth-rug.

“You never told me to go, sir,” he said, with the air of Casabianca, and King consigned him to the outer darkness.

But it was to a boot-cupboard under the staircase on the ground floor that he hastened, to loose the mirth that was destroying him. He had not drawn breath for a first whoop of triumph when two hands choked him dumb.

“Go to the dormitory and get me my things. Bring ‘em to Number Five lavatory. I’m still in tights,” hissed Stalky, sitting on his head. “Don’t run. Walk.”

But Beetle staggered into the form-room next door, and delegated his duty to the yet unenlightened McTurk, with an hysterical precis of the campaign thus far. So it was McTurk, of the wooden visage, who brought the clothes from the dormitory while Beetle panted on a form. Then the three buried themselves in Number Five lavatory, turned on all the taps, filled the place with steam, and dropped weeping into the baths, where they pieced out the war.

“Moi! Je! Ich! Ego!” gasped Stalky. “I waited till I couldn’t hear myself think, while you played the drum! Hid in the coal-locker—and tweaked Rabbits-Eggs—and Rabbits-Eggs rocked King. Wasn’t it beautiful? Did you hear the glass?”

“Why, he—he—he,” shrieked McTurk, one trembling finger pointed at Beetle.

“Why, I—I—I was through it all,” Beetle howled; “in his study, being jawed.”

“Oh, my soul!” said Stalky with a yell, disappearing under water.

“The—the glass was nothing. Manders minor’s head’s cut open. La—la—lamp upset all over the rug. Blood on the books and papers. The gum! The gum! The gum! The ink! The ink! The ink! Oh, Lord!”

Then Stalky leaped out, all pink as he was, and shook Beetle into some sort of coherence; but his tale prostrated them afresh.

“I bunked for the boot-cupboard the second I heard King go down-stairs. Beetle tumbled in on top of me. The spare key’s hid behind the loose board. There isn’t a shadow of evidence,” said Stalky. They were all chanting together.

“And he turned us out himself—himself—himself!” This from McTurk. “He can’t begin to suspect us. Oh, Stalky, it’s the loveliest thing we’ve ever done.”

“Gum! Gum! Dollops of gum!” shouted Beetle, his spectacles gleaming through a sea of lather. “Ink and blood all mixed. I held the little beast’s head all over the Latin proses for Monday. Golly, how the oil stunk! And Rabbits-Eggs told King to poultice his nose! Did you hit Rabbits-Eggs, Stalky?”

“Did I jolly well not.? Tweaked him all over. Did you hear him curse? Oh, I shall be sick in a minute if I don’t stop.”

But dressing was a slow process, because McTurk was obliged to dance when he heard that the musk basket was broken, and, moreover, Beetle retailed all King’s language with emendations and purple insets.

“Shockin’!’ said Stalky, collapsing in a helpless welter of half-hitched trousers. “So dam’ bad, too, for innocent boys like us! Wonder what they’d say at ‘St. Winifred’s, or the World of School.’—By gum! That reminds me we owe the Lower Third one for assaultin’ Beetle when he chivied Manders minor. Come on! It’s an alibi, Samivel; and, besides, if we let ‘em off they’ll be worse next time.”

The Lower Third had set a guard upon their form-room for the space of a full hour, which to a boy is a lifetime. Now they were busy with their Saturday evening businesses—cooking sparrows over the gas with rusty nibs; brewing unholy drinks in gallipots; skinning moles with pocket-knives; attending to paper trays full of silkworms, or discussing the iniquities of their elders with a freedom, fluency, and point that would have amazed their parents. The blow fell without warning. Stalky upset a form crowded with small boys among their own cooking utensils, McTurk raided the untidy lockers as a terrier digs at a rabbit-hole, while Beetle poured ink upon such heads as he could not appeal to with a Smith’s Classical Dictionary. Three brisk minutes accounted for many silkworms, pet larvae, French exercises, school caps, half-prepared bones and skulls, and a dozen pots of home-made sloe jam. It was a great wreckage, and the form-room looked as though three conflicting tempests had smitten it.

“Phew!” said Stalky, drawing breath outside the door (amid groans of “Oh, you beastly ca-ads! You think yourselves awful funny,” and so forth). “That’s all right. Never let the sun go down upon your wrath. Rummy little devils, fags. Got no notion o’ combinin’.”

“Six of ‘em sat on my head when I went in after Manders minor,” said Beetle. “I warned ‘em what they’d get, though.”

“Everybody paid in full—beautiful feelin’,” said McTurk absently, as they strolled along the corridor. “Don’t think we’d better say much about King, though, do you, Stalky?”

“Not much. Our line is injured innocence, of course—same as when the Sergeant reported us on suspicion of smoking in the bunkers. If I hadn’t thought of buyin’ the pepper and spillin’ it all over our clothes, he’d have smelt us. King was gha-astly facetious about that. ‘Called us bird-stuffers in form for a week.”

“Ah, King hates the Natural History Society because little Hartopp is president. Mustn’t do anything in the Coll. without glorifyin’ King,” said McTurk. “But he must be a putrid ass, know, to suppose at our time o’ life we’d go and stuff birds like fags.”

“Poor old King!” said Beetle. “He’s unpopular in Common-room, and they’ll chaff his head off about Rabbits-Eggs. Golly! How lovely! How beautiful! How holy! But you should have seen his face when the first rock came in! And the earth from the basket!”

So they were all stricken helpless for five minutes.

They repaired at last to Abanazar’s study, and were received reverently.

“What’s the matter?” said Stalky, quick to realize new atmospheres.

“You know jolly well,” said Abanazar. “You’ll be expelled if you get caught. King is a gibbering maniac.”

“Who? Which? What? Expelled for how? We only played the war-drum. We’ve got turned out for that already.”

“Do you chaps mean to say you didn’t make Rabbits-Eggs drunk and bribe him to rock King’s rooms?”

“Bribe him? No, that I’ll swear we didn’t,” said Stalky, with a relieved heart, for he loved not to tell lies. “What a low mind you’ve got, Pussy! We’ve been down having a bath. Did Rabbits-Eggs rock King? Strong, perseverin’ man King? Shockin’!”

“Awf’ly. King’s frothing at the mouth. There’s bell for prayers. Come on.”

“Wait a sec,” said Stalky, continuing the conversation in a loud and cheerful voice, as they descended the stairs. “What did Rabbits-Eggs rock King for?”

“I know,” said Beetle, as they passed King’s open door. “I was in his study.”

“Hush, you ass!” hissed the Emperor of China. “Oh, he’s gone down to prayers,” said Beetle, watching the shadow of the housemaster on the wall. “Rabbits-Eggs was only a bit drunk, swearin’ at his horse, and King jawed him through the window, and then, of course, he rocked King.”

“Do you mean to say,” said Stalky, “that King began it?”

King was behind them, and every well-weighed word went up the staircase like an arrow. “I can only swear,” said Beetle, “that King cursed like a bargee. Simply disgustin’. I’m goin’ to write to my father about it.”

“Better report it to Mason,” suggested Stalky. “He knows our tender consciences. Hold on a shake. I’ve got to tie my bootlace.”

The other study hurried forward. They did not wish to be dragged into stage asides of this nature. So it was left to McTurk to sum up the situation beneath the guns of the enemy.

“You see,” said the Irishman, hanging on the banister, “he begins by bullying little chaps; then he bullies the big chaps; then he bullies some one who isn’t connected with the College, and then catches it. Serves him jolly well right… I beg your pardon, sir. I didn’t see you were coming down the staircase.”

The black gown tore past like a thunder-storm, and in its wake, three abreast, arms linked, the Aladdin company rolled up the big corridor to prayers, singing with most innocent intention:

“Arrah, Patsy, mind the baby! Arrah, Patsy, mind the child! Wrap him up in an overcoat, he’s surely goin’ wild! Arrah, Patsy, mind the baby; just ye mind the child awhile! He’ll kick an’ bite an’ cry all night! Arrah, Patsy, mind the child!”

AN UNSAVORY INTERLUDE.

It was a maiden aunt of Stalky who sent him both books, with the inscription, “To dearest Artie, on his sixteenth birthday;” it was McTurk who ordered their hypothecation; and it was Beetle, returned from Bideford, who flung them on the window-sill of Number Five study with news that Bastable would advance but ninepence on the two; “Eric; or, Little by Little,” being almost as great a drug as “St. Winifred’s.” “An’ I don’t think much of your aunt. We’re nearly out of cartridges, too—Artie, dear.”

Whereupon Stalky rose up to grapple with him, but McTurk sat on Stalky’s head, calling him a “pure-minded boy” till peace was declared. As they were grievously in arrears with a Latin prose, as it was a blazing July afternoon, and as they ought to have been at a house cricket-match, they began to renew their acquaintance, intimate and unholy, with the volumes.

“Here we are!” said McTurk. “‘Corporal punishment produced on Eric the worst effects. He burned not with remorse or regret’—make a note o’ that, Beetle—’ but with shame and violent indignation. He glared’—oh, naughty Eric! Let’s get to where he goes in for drink.”

“Hold on half a shake. Here’s another sample. ‘The Sixth,’ he says,‘is the palladium of all public schools.’ But this lot—” Stalky rapped the gilded book—“can’t prevent fellows drinkin’ and stealin’, an’ lettin’ fags out of window at night, an’—an’ doin’ what they please. Golly, what we’ve missed—not goin’ to St. Winifred’s!…”

“I’m sorry to see any boys of my house taking so little interest in their matches.”

Mr. Prout could move very silently if he pleased, though that is no merit in a boy’s eyes. He had flung open the study-door without knocking—another sin—and looked at them suspiciously. “Very sorry, indeed, I am to see you frowsting in your studies.”

“We’ve been out ever since dinner, sir,” said. McTurk wearily. One house-match is just like another, and their “ploy” of that week happened to be rabbit-shooting with saloon-pistols.

“I can’t see a ball when it’s coming, sir,” said Beetle. “I’ve had my gig-lamps smashed at the Nets till I got excused. I wasn’t any good even as a fag, then, sir.”

“Tuck is probably your form. Tuck and brewing. Why

Comments (0)