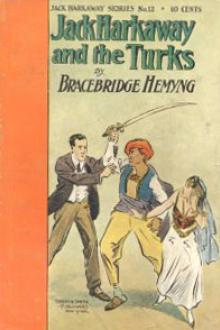

Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks - Bracebridge Hemyng (10 ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Bracebridge Hemyng

- Performer: -

Book online «Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks - Bracebridge Hemyng (10 ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Bracebridge Hemyng

"That's your chance; you have only to take them up to your place. Once there, you will do as you please with them."

"There is no danger?"

"What can there be!"

"Only this—suppose that you were mistaken?"

Markby was visibly offended at this.

"If you think that likely after all I have told you, take my advice and have nothing whatever to do with them. I don't want to expose you to any risk that you think you ought not to run."

Lenoir appeared to waver momentarily.

Markby eyed him anxiously for awhile, until Lenoir, with an air of resolution, exclaimed—

"Hang the risk. I'll go for it neck or nothing."

"And you will take them there to-night."

"I will."

"Good! You'll have no cause to repent your decision. They'll do you a turn that you little contemplate."

"Right! Now off with you."

"I'm gone."

And away he went.

"What a strange fellow that Markby is," thought Pierre Lenoir, looking after him. "What an odd laugh he has."

Alas! Pierre Lenoir had good reason to bear that laugh in mind.

But we must not anticipate.

As soon as Markby was fairly out of sight, he beckoned over to a young man in white blouse and a cap, who had walked along on the opposite side of the way, keeping Markby in view all the while without appearing to notice him.

The fellow in the blouse ran across at once.

"Well, how's it going?"

"Beautiful," returned Markby, "nothing could be better. Already have Harkaway and his hard-knuckled companion, Girdwood, been seen in Lenoir's society. But before the day is over they will be seen in the Caveaux themselves, where proofs of their guilt will spring up hydra-headed from the very ground."

"And what will it end in?" asked the other, eagerly.

"The galleys," returned Markby, with fierce intensity.

"Beautiful!" exclaimed the man in the blouse, with unfeigned admiration. "You always must have been a precious sight downier than I thought. Why, your old man was no fool. He made a brown or two floating his coffins, but he was a guileless pup compared to you."

"You keep watch," said Markby, hurriedly; "and be ready for any emergency. It is a bold stroke we are playing for. Lenoir is a desperate ruffian, and the least mistake in the business would be something which I for one don't care to contemplate."

"Lenoir be blowed," replied the man in the blouse; "the only people I care about if we should go and make a mess of the job is, firstly—Jack Harkaway, and secondly, his pal Harry Girdwood, which a harder fist than his I have seldom received on my unlucky snuffer-tray."

And he was gone.

CHAPTER XCI.

MARKBY'S NEXT STEP—THE PREFECT OF POLICE—THE PLOT THICKENS—A GLIMPSE OF MARKBY'S PURPOSE—A DOUBLE TRAITOR—DEADLY PERIL.

Markby went off muttering to himself.

"Wish that scamp could only share the fate I have reserved for that accursed Harkaway. However, I can't manage that, so I must be thankful for small mercies."

A short walk brought this Markby to the office of the prefect of police, and his business being of considerable importance, he was fortunate in soon obtaining an interview with that great man himself.

"This is an excellent opportunity," said the head of the police, "if your information is thoroughly reliable, although I confess that it almost sounds too good to be true."

"Pardon me, monsieur," said Markby, "the expression you use sounds as though I had got information second-hand; I am a principal. On the 10th, you will please to remember. I have to be of the party."

"It is a very important matter," said the prefect, "that I will not attempt to disguise from you. This Lenoir is evidently at the head of a gigantic conspiracy. We have been long seeking to discover how he disposed of his counter——"

"Stock," said Markby, interrupting the prefect, with a smile. "He is the quintessence of caution, sir, and he never alludes to it by any other term."

"You really think that these English people are their confidants?"

"The chief confederates; yes. They are the heads of the English part of our scheme."

"How many men should you require?" demanded the prefect, changing the subject abruptly.

"A dozen fully armed, in plain clothes. These can descend into the caveaux to make the capture."

"A dozen!"

"Yes."

"So many!"

"You don't know Lenoir," said Markby; "he's the very devil when he's aroused. A dozen will have all their work to do. As for the two Englishmen——"

"They are young," exclaimed the prefect.

"They are young fiends. I have seen them fight like devils. They are just as dangerous as Lenoir. They are an cunning as the evil one himself, and will gammon even you, by their plausible tales."

"Let me see," said the prefect, thoughtfully. "I will take note of the names which you tell me they are likely to assume."

"One has been calling himself Jack Harkaway."

"And the other?"

"Harry Girdwood."

"Good—and you can prove that both the persons whose names are assumed are in Turkey?"

"I can."

"Very good," said the prefect, rising, to intimate that the intercourse was over. "Our men shall be there in force for the capture."

CHAPTER XCII.

THE HARKAWAY'S GUIDE—LENOIR'S MUSEUM—THE CAVEAUX, AND WHAT THEY SAW THERE—THE MEDALS—THE TRUTH AT LAST—A COINER'S TRADE—AN ALARM—A DESPERATE FELLOW.

"Here we are again, sir," said Harry Girdwood, stepping up to Pierre Lenoir; "but I fear we are taking a great liberty in asking you to cicerone such a large party as we muster here."

Lenoir smiled.

It was not a free, frank smile.

To tell the truth, he was a bit annoyed, for besides the two youths there was Mole, and the attendant darkeys with them, Tinker and Bogey.

Lenoir was a cautious man, and he did not care to run risks.

"Are they friends and confidants of yours?" he asked, rather pointedly.

It was an odd speech to make, but as he smiled slightly, they took it for a sort of joke.

"Oh, yes, they are confidential friends," returned Harry Girdwood, smiling.

"Very good, let us begin our look round. We will walk along the quays if you like, and thence past the Hôtel de Ville. I shall show you several objects of undoubted interest," said Lenoir, significantly.

He led the way on.

Jack fell back a few paces, walking on with Harry Girdwood.

"He's a very odd fellow," whispered the latter.

"Very."

Lenoir led them over the town before he ventured to approach the Caveaux.

"I have a little museum not far away," he said.

"I am afraid we shall be intruding," began Jack.

"Not a bit," protested Lenoir.

The snuggery in question was situated at some little distance from the town, and away from the main road.

The cottage was only a one-story building.

"His museum is not very extensive," whispered Harry Girdwood to his companion, "if it is that cottage."

Lenoir was remarkably quick-eared.

"My museum is cunningly arranged," he said to Jack, looking over his shoulder as he walked on; "you don't get all over it at once. Here we are."

They had reached the threshold, and opening the door, he led the way in.

It was a neat little cottage interior, with nothing about it to attract attention.

Passing through the first room, Lenoir conducted them to a sort of out-house beyond.

Here they came upon the first surprise.

He opened a door which apparently shut in a cupboard, and this, to their intense astonishment, revealed a flight of stone steps which seemingly led into the very bowels of the earth.

"Hallo!" exclaimed Jack; "why, what's this?"

"I thought I should astonish you, now," said Lenoir, with his same calm smile.

"What is this place?"

"There is a whole series of caves below these, apparently natural formations. The only way I can account for them myself is that at some time or other some experimental mining operations have gone on there. Would you like to go down and see the place?"

"With pleasure," returned Jack, eagerly.

"Allow me to lead the way."

When they had descended a few steps, Jack half repented.

This man was a stranger to them, and he had brought them to a very wild and out-of-the-way place.

Had he any evil purpose in bringing them there?

Jack stood wavering for a few seconds—no more.

"We are four," he said to himself, "four without counting Mr. Mole; they must be a pretty tough lot to frighten us much, after all said and done."

So saying down he went.

The others followed close behind him.

At the base of the flight of steps they found themselves in a spacious vault that was unpleasantly dark.

"Allow me to lead the way now," said Lenoir, passing on. "Follow me closely; there is no fear of stumbling, there is nothing in the way."

So saying, he conducted them through this opening, which, by the way, was so low that they had to stoop in passing under, and found themselves now in a narrow cave, which reminded young Jack forcibly of the dungeon and its approach of Sir Walter Raleigh, in the Tower of London.

"What do you think of this place?" demanded the guide.

"A very curious sight," was the reply. "You put all this space to no use?"

"Pardon me," said Lenoir; "I practise my favorite hobby here."

"Here!"

"Yes—or rather in the next cellar beyond."

"And what may be that favourite hobby?"

"Medalling," was Lenoir's reply.

And again he shot at his questioners one of those peculiar glances which had so astonished them before.

"I should like to see some of your work," said Jack.

"I thought you would," said Lenoir, with a quiet chuckle.

Lenoir led the way into the next cellar or cavern, and here they came suddenly upon a complete change of scene.

Here they saw a furnace, with melting pots, bars of metal, moulds, files, batteries, and all the necessary accessories for the manufacture of medals.

Upon a flat stone slab was a pile of medals, all of the same pattern precisely.

"Just examine those, Mr. Harkaway," said Pierre Lenoir, "and tell me what you think them."

Jack put his finger through the glittering heap, and they fell to the table with a bright clear ring that considerably astonished him.

"Why, they are silver!"

Lenoir smiled.

"Very good, aren't they?"

"Very!"

Jack here made a discovery, upon examining them more closely.

"They are five-franc pieces!" he said, with a puzzled expression.

"Of course they are—and beauties they are too!"

"There's not much risk in getting rid of those, I should say?"

"Risk!" iterated Harry Girdwood.

"Aye!"

"Why risk?"

"I mean that no one could detect the difference very easily. Why, they deceived you," he added, turning to Jack, with an air of conscious pride.

"Upon my life, I don't understand what you mean," said Jack.

Lenoir looked serious for a moment.

Then he burst out into a boisterous fit of merriment.

"You are really over-cautious, young gentleman," he said.

"Over-cautious?"

"Why, yes—why, yes. Wherefore this reserve? Why should you pretend not to understand? Don't you see," he added, with a cunning leer, "that I can make these medals as perfectly as they can at the Hôtel de la Monnaie, our French Mint?"

"So I see," said Jack.

A faint light began to dawn upon Harry Girdwood—not too soon, the reader will say.

"It is rather a dangerous pastime, Mr. Lenoir, this medalling fancy of yours," he said.

"No," said Lenoir, pointedly, "the danger is not there; the danger of this pastime, as you call it, is in disposing of my beautiful medals."

"Dear me, sir," said Mr. Mole. "Do you sell them?"

"Yes."

"How much?"

"The five-franc pieces two francs and a half," replied Lenoir, "and so on throughout until we get up to the louis, the twenty-franc pieces; those I can do for seven francs. You can pass them without risk."

This told all.

Jack and his friends were astounded.

"Are you making us overtures to join you in passing bad money?" demanded young Jack.

"Not bad money," returned Lenoir, "very good money—all my own make."

"It is very evident that you do not know us," said Harry Girdwood, "and so are considerably mistaken. Why you have brought us here and placed yourself in our power, it is utterly beyond me to understand."

Lenoir stared.

"What!"

"The position is most embarrassing," said Jack. "To do our duty would be to repay by great ingratitude your kindness in guiding us about the town, for we ought to denounce you to the police authorities."

This speech partook of the nature of a threat and Pierre Lenoir was up in an instant.

"The worst day's work of your life would be that," he said, fiercely. "No man

Comments (0)