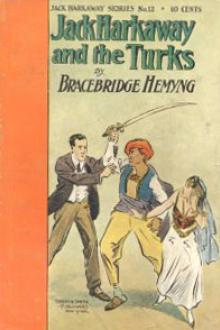

Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks - Bracebridge Hemyng (10 ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Bracebridge Hemyng

- Performer: -

Book online «Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks - Bracebridge Hemyng (10 ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Bracebridge Hemyng

"Mind you don't get finished off first," said the waggoner significantly.

As he spoke, he was looking up over his conqueror's shoulder.

Lenoir perceived this, but thought it only a ruse to get him to shift his hold.

So, with a contemptuous smile, he raised his clenched fist to deal the luckless waggoner a blow that was to knock every scrap of sense out of his unfortunate cranium.

"Take that!"

But before the waggoner could get it, Lenoir received something himself that sent him to earth with a hollow groan—felled like a bullock beneath the butcher's pole-axe.

Somebody had after all been concealed in the waggon.

That somebody was Herbert Murray himself.

The English youth had heard the scuffle, and seeing his opportunity, he slid out of his place of concealment and joined in the fight at the very right moment.

The waggoner shook himself together.

"That was neatly done, camarade," he said.

"I was just in time," said Murray; "look after him. He is wanted by the police; a desperate customer. They are after him now."

"He's very quiet," said the waggoner, with a curious glance.

"He's not dead," returned Murray; "he has his destiny to fulfil yet."

"What may that be?"

"The galleys," was the reply.

The waggoner stared hard at young Murray.

"I don't like the look of you much more than that of the beast lying there," he thought to himself; "mind you don't keep him company in the galleys."

An odd fancy to cross a stranger's mind.

Was it prophetic?

CHAPTER XCV.

PLANS FOR OUR FRIENDS' RELEASE—MURRAY'S COUNTER-PLOT—THE LETTER, AND HOW IT WAS INTERCEPTED—HERBERT MURRAY TRIUMPHS—CHIVEY WORKS THE ARTFUL DODGE.

"Well," exclaimed the unfortunate Mole, "this is a nice go!"

"I'm glad you think it nice," said young Jack, bitterly.

As they spoke, they were being led through the streets of Marseilles, handcuffed and two abreast, with a brace of gendarmes between each couple.

The people flocked out to stare at the "notorious gang of forgers, which"—so rang the report—"had just been captured by the police, after making a desperate resistance."

The first impulse of Jack Harkaway himself had been naturally to resist his captors.

But he was speedily shown the uselessness of such a course.

When they were brought up before the judge for examination, they protested their innocence, and told the simple truth.

But this did not avail them.

Herbert Murray had prepared the way for their statements to be regarded as falsehoods.

By this means, when Jack protested that his name was Harkaway, it went clearly against him, inasmuch as it corroborated what Murray had said.

So they were remanded, one and all, and sent back to the cells.

Mr. Mole's indignation could not be subdued.

"These people are worse than savages!" he exclaimed; "but we'll let them know. They shall make us ample reparation for this indignity."

He talked threateningly of the British ambassador, and made all kinds of threats.

But he was poohpoohed by the authorities.

Harry Girdwood was the only one of the party who kept his coolness.

He put forth his request with so much earnestness, to be allowed to see the English consul, that his request was granted at once.

He drew up a letter and entrusted it to the gaoler, who promised to have it forwarded.

Now this became known to Herbert Murray, and he then saw that he had still a task of no ordinary difficulty before him—that it was not sufficient alone to have his hated enemies arrested.

The greater difficulty by far was to keep them now that he had secured them.

In this crisis he once more consulted with his worthless servant and confederate, Chivey.

"Our next job," said Chivey, doubtfully, "is to get at the gaoler, and stop the letter he has received from reaching its destination."

"How would you set to work?" demanded his master.

"You do what you can inside," said Chivey, "and I'll lay in wait for the messenger with the letter outside in case you fail."

"Good."

"You can buy that gaoler," said the tiger.

"I will."

"Do so. Your task is the easier of the two. Ten francs ought to square him."

"It ought," said Murray; "but I question if it will."

Murray was doomed to a sad disappointment in his operations, for do what he would, he could not "get at" the man charged with delivering the Harkaways' letters.

But he contrived to ascertain who the man was, and to give a description of him to the tiger.

Chivey saw the man come out of the prison, and he thought over various plans for getting hold of the letter which he knew that he must be carrying.

His first idea was to go up to him and address him straight off upon the subject; but this would not do.

The messenger would in all probability take the alarm.

He next had an idea of following up the messenger, and after giving him a crack on the head, rifling his pockets.

This idea he abandoned even sooner than the first, and this for sundry wholesome reasons.

Firstly, the man's road did not lead him into any sufficiently quiet places for such an attempt.

Secondly, the man was a tough-looking customer, and an awkward fellow to tackle.

And thirdly—but the second reason sufficed to send Chivey's mind away from all ideas of violence.

No; deeds of daring were not at all in Chivey's line.

He had a notion, however, and this was to go as fast as he could to the British consul's, and there to be ready for the messenger when he came.

His plans were not more matured than this; but chance seemed to very much favour this precious pair of youthful scamps—for the time being, at any rate.

Chivey timed his own arrival at the consul's residence, so as to be there just a few minutes in advance of the prison messenger.

The servant who admitted him was an Englishman, and told Chivey that his master was particularly engaged just then, and would not be visible for some considerable time.

"Be so good as to ask when I can see your master," said Chivey, with an air of lofty condescension.

"I must not disturb him now," said the servant.

"He will be very vexed with you if you don't," returned Chivey, "when he knows my business."

The servant being only impressed with this threat, went off at once to obey the insidious tiger, who of course was not in livery.

Barely had the consul's servant disappeared, when the messenger from the prison entered.

Chivey recognised him instantly.

"Une lettre pour Monsieur le Consul," said the messenger.

Chivey held out his hand, and the man, taking it for granted that Chivey belonged to the consular establishment, gave it to him.

"Il y a une réponse—there is an answer," said the messenger.

"It will be forwarded," returned Chivey, with cool presence of mind.

"I ought to take it with me," said the messenger.

"I can't disturb his excellency now," replied the tiger; "those are my master's express orders, which I can't presume to disobey. He will send the answer on immediately it is ready."

The man paused.

"The consul was expecting this letter," said Chivey, moving towards the door, "and he told me particularly that he would send the answer on."

"Puisqu'il est ainsi," said the man, dubiously. "Since it must be so, I suppose I had better leave the letter."

"Of course you had," returned Chivey, closing the door. "I daresay you will get the answer within an hour."

At that very moment the servant returned with a message from the consul to the effect that in half an hour he could be seen, if the applicant would call again.

"Very good," said Chivey, in the same patronising manner, "you may tell your master that I will look back later on."

"Very well, sir."

Chivey walked out, chuckling inwardly at the success of his mission.

"What could be easier?" said the Cockney scamp to himself; "shelling peas is a fool to it."

But before he could get fairly over the threshold, the servant stopped him with a question that startled him a little, and well-nigh made him lose his presence of mind.

"The man who called just now, sir, he left a letter."

"Eh? Oh, yes!"

"For you, sir?"

"Yes," added Chivey with the coolest effrontery. "My servant knew that I had come on here; thinking to be detained some time with his excellency the consul, I left word at my hotel where I was coming, and he followed me here with a letter."

"Oh, I see, sir," returned the servant, obsequiously, "quite so, sir, beg pardon, sir."

"Not at all, my good man, not at all," returned Chivey, superciliously; "you are a very civil, well-spoken young man—here is a trifle for you."

He passed the servant a large silver coin, and walked on.

The servant bowed again and examined the coin, in the process of bobbing his head.

"Five francs," said the consul's servant, to himself; "he's a real swell, anyone can see."

One word more.

The five-franc piece which had in no slight degree biassed the servant's opinion of the visitor, was one of Pierre Lenoir's admirable manufacture.

"Let's have a look at the letter, Chivey," said Herbert Murray, as soon as his servant got back.

But Chivey seemed to hesitate.

"Come, come," said Murray, "we shall not quarrel about the terms."

"We oughnt't to," returned the tiger, "for it's worth a Jew's eye."

Murray tore the letter open and read it down eagerly.

As it throws some additional light upon the actual state of affairs with the Harkaway party, possibly it may be as well to give the letter of young Jack to the consul verbatim.

It was dated from the prison.

"Sir,—I wish to solicit your immediate assistance in getting released from the above uncomfortable premises, where, in company with a party of friends and fellow-travellers, I have been by a singular accident carried by the police. From scraps of information I have gained while here, I believe I am correct in asserting that we have fallen into a trap, cunningly prepared for us by an unscrupulous fellow-countryman of ours, who has cogent reasons for wishing us out of the way, and has accordingly caused me and my friends to be arrested as coiners. The person in question is named Herbert Murray, but I am unable to say under what alias he is at present known in this part of the world. I mention this that you may be able to keep an eye upon the individual pending our release on bail, for I presume that bail is a French institution. My signature will serve you for reference on me, as it may readily be identified at my father's bankers here, Messrs. B. Fould & Co.

"Your obedient servant,

"Jack Harkaway."

Herbert Murray pursed his brows as he read on.

"What do you think of that?" demanded Chivey.

"Queer!"

"Precious queer."

"The one lesson to be learnt from it, Chivey," said his master, "is to stop all correspondence between the prisoners and the consul."

"And push forward the trial as much as possible."

"Yes, and get together as many reliable witnesses as we can——"

"Buy them at a pound apiece," concluded Chivey.

"Right," said Herbert Murray, with a mischievous grin; "forewarned, forearmed; we hold them now and we'll keep them——"

"Please the pigs," concluded Chivey fervently.

CHAPTER XCVI.

OUR FRIENDS IN DURANCE VILE—A STROKE FOR LIBERTY—THE PRISONERS' PLOT—MOLE IS PRESCRIBED FOR—A FRIEND IN NEED—HOPES AND MISGIVINGS—"OLD WET BLANKET."

"It's very odd."

"Very."

"And scarcely polite," suggested Mr. Mole.

"Well, scarcely."

"That makes the fourth letter I have written to him, and he doesn't even condescend to notice them."

"Very odd."

"Very."

But while all the sufferers by the seeming neglect of the consul were expressing themselves so freely in the matter, old Sobersides, as Jack called his comrade, Harry Girdwood, remained silent and meditative.

Jack had great faith in his thoughtful chum.

"A penny for your thoughts, Harry," said he.

"I'll give them for nix," returned Harry Girdwood, gaily.

"Out with it."

"I was wondering whether, while you are all blaming the poor consul, he has ever received your letters."

"What, the four?"

"Yes."

"Of course."

"I don't see it."

"But, my dear fellow, consider. One may have miscarried—or two—but hang it! all four can't have gone wrong."

"Of course not," said Mole, with the air of a man who puts a final stop to all arguments.

"There I beg leave to differ with you all."

"Why?"

"The letters have not reached the consul, perhaps; they may have been intercepted."

"By whom?" was Jack's natural question.

"Can't say positively; possibly by Murray."

"Is

Comments (0)