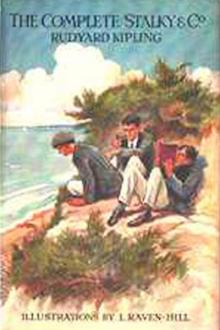

Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗

- Author: Rudyard Kipling

- Performer: -

Book online «Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗». Author Rudyard Kipling

Tulke gasped and wheeled. Solemnly and conscientiously Mary kissed him twice, and the luckless prefect fled.

She stepped into the shop, her eyes full of simple wonder. “Kissed ‘un?” said Stalky, handing over the money.

“Iss, fai! But, oh, my little body, he’m no Colleger. ‘Zeemed tu-minded to cry, like.”

“Well, we won’t. Yell couldn’t make us cry that way,” said McTurk. “Try.”

Whereupon Mary cuffed them all round.

As they went out with tingling cars, said Stalky generally, “Don’t think there’ll be much of a prefects’ meeting.”

“Won’t there, just!” said Beetle. “Look here. If he kissed her—which is our tack—he is a cynically immoral hog, and his conduct is blatant indecency. Conferorationes_Regis_furiosissimi_, when he collared me readin’ “Don Juan.’”

“‘Course he kissed her,” said McTurk. “In the middle of the street. With his house-cap on!”

“Time, 3.57 p.m. Make a note o’ that. What d’you mean, Beetle?” said Stalky.

“Well! He’s a truthful little beast. He may say he was kissed.”

“And then?”

“Why, then!” Beetle capered at the mere thought of it. “Don’t you see? The corollary to the giddy proposition is that the Sixth can’t protect ‘emselves from outrages an’ ravishin’s. Want nursemaids to look after ‘em! We’ve only got to whisper that to the Coll. Jam for the Sixth! Jam for us! Either way it’s jammy!”

“By Gum!” said Stalky. “Our last term’s endin’ well. Now you cut along an’ finish up your old rag, and Turkey and me will help. We’ll go in the back way. No need to bother Randall.”

“Don’t play the giddy garden-goat, then?” Beetle knew what help meant, though he was by no means averse to showing his importance before his allies. The little loft behind Randall’s printing office was his own territory, where he saw himself already controlling the “Times.” Here, under the guidance of the inky apprentice, he had learned to find his way more or less circuitously about the case, and considered himself an expert compositor.

The school paper in its locked formes lay on a stone-topped table, a proof by the side; but not for worlds would Beetle have corrected from the mere proof. With a mallet and a pair of tweezers, he knocked out mysterious wedges of wood that released the forme, picked a letter here and inserted a letter there, reading as he went along and stopping much to chuckle over his own contributions.

“You won’t show off like that,” said McTurk, “when you’ve got to do it for your living. Upside down and backwards, isn’t it? Let’s see if I can read it.”

“Get out!” said Beetle. “Go and read those formes in the rack there, if you think you know so much.”

“Formes in a rack! What’s that? Don’t be so beastly professional.”

McTurk drew off with Stalky to prowl about the office. They left little unturned.

“Come here a shake, Beetle. What’s this thing?” aid Stalky, in a few minutes. “Looks familiar.”

Said Beetle, after a glance: “It’s King’s Latin prose exam. paper. In—InVarrem: actioprima_. What a lark!”

“Think o’ the pure-souled, high-minded boys who’d give their eyes for a squint at it!” said McTurk.

“No, Willie dear,” said Stalky; “that would be wrong and painful to our kind teachers. You wouldn’t crib, Willie, would you?”

“Can’t read the beastly stuff, anyhow,” was the reply. “Besides, we’re leavin’ at the end o’ the term, so it makes no difference to us.”

“‘Member what the Considerate Bloomer did to Spraggon’s account of the Puffin’ton Hounds? We must sugar Mr. King’s milk for him,” said Stalky, all lighted from within by a devilish joy. “Let’s see what Beetle can do with those forceps he’s so proud of.”

“Don’t see now you can make Latin prose much more cock-eye than it is, but we’ll try,” said Beetle, transposing an aliud and Asiae from two sentences. “Let’s see! We’ll put that full-stop a little further on, and begin the sentence with the next capital. Hurrah! Here’s three lines that can move up all in a lump.”

“‘One of those scientific rests for which this eminent huntsman is so justly celebrated.’” Stalky knew the Puffington run by heart.

“Hold on! Here’s a vol—_voluntate_quidnam_ all by itself,” said McTurk.

“I’ll attend to her in a shake. Quidnam goes after Dolabella.”

“Good old Dolabella,” murmured Stalky. “Don’t break him. Vile prose Cicero wrote, didn’t he? He ought to be grateful for—”

“Hullo!” said McTurk, over another forme. “What price a giddy ode? Qui—_quis_ —oh, it’s Quismulta_gracilis_, o’ course.”

“Bring it along. We’ve sugared the milk here,” said Stalky, after a few minutes’ zealous toil. “Never thrash your hounds unnecessarily.”

“Quismunditiis_? I swear that’s not bad,” began Beetle, plying the tweezers. “Don’t that interrogation look pretty? Heuquoties_fidem_! That sounds as if the chap were anxious an’ excited. Cuiflavam_religasinrosa_—Whose flavor is relegated to a rose. MutatosqueDeos_flebitinantro.”

“Mute gods weepin’ in a cave,” suggested Stalky. “‘Pon my Sam, Horace needs as much lookin’ after as—Tulke.”

They edited him faithfully till it was too dark to see.

“‘Aha! Elucescebat, quoth our friend.’ Ulpian serves my need, does it? If King can make anything out of that, I’m a blue-eyed squatteroo,” said Beetle, as they slid out of the loft window into a back alley of old acquaintance and started on a three-mile trot to the College. But the revision of the classics had detained them too long. They halted, blown and breathless, in the furze at the back of the gasometer, the College lights twinkling below, ten minutes at least late for tea and lock-up.

“It’s no good,” puffed McTurk. “Bet a bob Foxy is waiting for defaulters under the lamp by the Fives Court. It’s a nuisance, too, because the Head gave us long leave, and one doesn’t like to break it.”

“‘Let me now from the bonded ware’ouse of my knowledge,’” began Stalky.

“Oh, rot! Don’t Jorrock. Can we make a run for it?” snapped McTurk.

“‘Bishops’ boots Mr. Radcliffe also condemned, an’ spoke ‘ighly in favor of tops cleaned with champagne an’ abricot jam.’ Where’s that thing Cokey was twiddlin’ this afternoon?”

They heard him groping in the wet, and presently beheld a great miracle. The lights of the Coastguard cottages near the sea went out; the brilliantly illuminated windows of the Golf-club disappeared, and were followed by the frontages of the two hotels. Scattered villas dulled, twinkled, and vanished. Last of all, the College lights died also. They were left in the pitchy darkness of a windy winter’s night.

“‘Blister my kidneys. It is a frost. The dahlias are dead!’” said Stalky. “Bunk!”

They squattered through the dripping gorse as the College hummed like an angry hive and the dining-rooms chorused, “Gas! gas! gas!” till they came to the edge of the sunk path that divided them from their study. Dropping that ha-ha like bullets, and rebounding like boys, they dashed to their study, in less than two minutes had changed into dry trousers and coat, and, ostentatiously slippered, joined the mob in the dining-hall, which resembled the storm-centre of a South American revolution.

“‘Hellish dark and smells of cheese.’” Stalky elbowed his way into the press, howling lustily for gas. “Cokey must have gone for a walk. Foxy’ll have to find him.”

Prout, as the nearest housemaster, was trying to restore order, for rude boys were flicking butter-pats across chaos, and McTurk had turned on the fags’ tea-urn, so that many were parboiled and wept with an unfeigned dolor. The Fourth and Upper Third broke into the school song, the “Vive la Compagnie,” to the accompaniment of drumming knife-handles; and the junior forms shrilled bat-like shrieks and raided one another’s victuals. Two hundred and fifty boys in high condition, seeking for more light, are truly earnest inquirers.

When a most vile smell of gas told them that supplies had been renewed, Stalky, waistcoat unbuttoned, sat gorgedly over what might have been his fourth cup of tea. “And that’s all right,” he said. “Hullo! ‘Ere’s Pomponius Ego!”

It was Carson, the head of the school, a simple, straight-minded soul, and a pillar of the First Fifteen, who crossed over from the prefects’ table and in a husky, official voice invited the three to attend in his study in half an hour. “Prefects’ meetin’! Prefects’ meetin’!” hissed the tables, and they imitated barbarically the actions and effects of the ground-ash.

“How are we goin’ to jest with ‘em?” said Stalky, turning half-face to Beetle. “It’s your play this time!”

“Look here,” was the answer, “all I want you to do is not to laugh. I’m goin’ to take charge o’ young Tulke’s immorality—_a’la King, and it’s goin’ to be serious. If you can’t help laughin’ don’t look at me, or I’ll go pop.”

“I see. All right,” said Stalky.

McTurk’s lank frame stiffened in every muscle and his eyelids dropped half over his eyes. That last was a war-signal.

The eight or nine seniors, their faces very set and sober, were ranged in chairs round Carson’s severely Philistine study. Tulke was not popular among them, and a few who had had experience of Stalky and Company doubted that he might, perhaps, have made an ass of himself. But the dignity of the Sixth was to be upheld. So Carson began hurriedly: “Look here, you chaps, I’ve—we’ve sent for you to tell you you’re a good deal too cheeky to the Sixth—have been for some time—and—and we’ve stood about as much as we’re goin’ to, and it seems you’ve been cursin’ and swearin’ at Tulke on the Bideford road this afternoon, and we’re goin’ to show you you can’t do it. That’s all.”

“Well, that’s awfully good of you,” said Stalky, “but we happen to have a few rights of our own, too. You can’t, just because you happen to be made prefects, haul up seniors and jaw ‘em on spec., like a housemaster. We aren’t fags, Carson. This kind of thing may do for Davies Tertius, but it won’t do for us.”

“It’s only old Prout’s lunacy that we weren’t prefects long ago. You know that,” said McTurk. “You haven’t any tact.”

“Hold on,” said Beetle. “A prefects’ meetin’ has to be reported to the Head. I want to know if the Head backs Tulke in this business?”

“Well—well, it isn’t exactly a prefects’ meeting,” said Carson. “We only called you in to warn you.”

“But all the prefects are here,” Beetle insisted. “Where’s the difference?”

“My Gum!” said Stalky. “Do you mean to say you’ve just called us in for a jaw—after comin’ to us before the whole school at tea an’ givin’ ‘em the impression it was a prefects’ meeting? ‘Pon my Sam, Carson, you’ll get into trouble, you will.”

“Hole-an’-corner business—hole-an’-corner business,” said McTurk, wagging his head. “Beastly suspicious.”

The Sixth looked at each other uneasily. Tulke had called three prefects’ meetings in two terms, till the Head had informed the Sixth that they were expected to maintain discipline without the recurrent menace of his authority. Now, it seemed that they had made a blunder at the outset, but any right-minded boy would have sunk the legality and been properly impressed by the Court. Beetle’s protest was distinct “cheek.”

“Well, you chaps deserve a lickin’,” cried one Naughten incautiously. Then was Beetle filled with a noble inspiration.

“For interferin’ with Tulke’s amours, eh?” Tulke turned a rich sloe color. “Oh, no, you don’t! “Beetle went on. “You’ve had your innings. We’ve been sent up for cursing and swearing at you, and we’re goin’ to be let off with a warning! Are we? Now then, you’re going to catch it.”

“I—I—I” Tulke began. “Don’t let that young devil start jawing.”

“If you’ve anything to say you must say it decently,” said Carson.

“Decently? I will. Now look here. When we went into Bideford we met this ornament of the Sixth—is that decent

Comments (0)