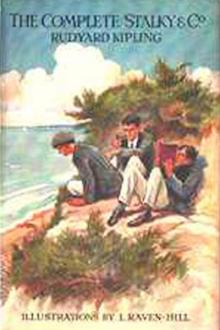

Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗

- Author: Rudyard Kipling

- Performer: -

Book online «Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗». Author Rudyard Kipling

“But o’ course he was blind squiffy when he wrote the paper. I hope you explained that?” said Stalky.

“Oh, yes. I told Tulke so. I said an immoral prefect an’ a drunken housemaster were legitimate inferences. Tulke nearly blubbed. He’s awfully shy of us since Mary’s time.”

Tulke preserved that modesty till the last moment—till the journey-money had been paid, and the boys were filling the brakes that took them to the station. Then the three tenderly constrained him to wait a while.

“You see, Tulke, you may be a prefect,” said Stalky, “but I’ve left the Coll. Do you see, Tulke, dear?”

“Yes, I see. Don’t bear malice, Stalky.”

“Stalky? Curse your impudence, you young cub,” shouted Stalky, magnificent in top-hat, stiff collar, spats, and high-waisted, snuff-colored ulster. “I want you to understand that I’m Mister Corkran, an’ you’re a dirty little schoolboy.”

“Besides bein’ frabjously immoral,” said McTurk. “Wonder you aren’t ashamed to foist your company on pure-minded boys like us.”

“Come on, Tulke,’ cried Naughten, from the prefects’ brake.

“Yes, we’re comin’. Shove up and make room, you Collegers. You’ve all got to be back next term, with your ‘Yes, sir,’ and ‘Oh, sir,’ an’ ‘No sir’ an’ ‘Please sir’; but before we say good-by we’re going to tell you a little story. Go on, Dickie” (this to the driver); “we’re quite ready. Kick that hat-box under the seat, an’ don’t crowd your Uncle Stalky.”

“As nice a lot of high-minded youngsters as you’d wish to see,” said McTurk, gazing round with bland patronage. “A trifle immoral, but then—boys will be boys. It’s no good tryin’ to look stuffy, Carson. Mister Corkran will now oblige with the story of Tulke an’ Mary Yeo!”

SLAVES OF THE LAMP.

Part II.

That very Infant who told the story of the capture of Boh Na Ghee [_A_Conference_ _ofthePowers_: “Many Inventions”] to Eustace Cleaver, novelist, inherited an estateful baronetcy, with vast revenues, resigned the service, and became a landholder, while his mother stood guard over him to see that he married the right girl. But, new to his position, he presented the local volunteers with a full-sized magazine-rifle range, two miles long, across the heart of his estate, and the surrounding families, who lived in savage seclusion among woods full of pheasants, regarded him as an erring maniac. The noise of the firing disturbed their poultry, and Infant was cast out from the society of J.P.‘s and decent men till such time as a daughter of the county might lure him back to right thinking. He took his revenge by filling the house with choice selections of old schoolmates home on leave—affable detrimentals, at whom the bicycle-riding maidens of the surrounding families were allowed to look from afar. I knew when a troop-ship was in port by the Infant’s invitations. Sometimes he would produce old friends of equal seniority; at others, young and blushing giants whom I had left small fags far down in the Lower Second; and to these Infant and the elders expounded the whole duty of man in the Army.

“I’ve had to cut the service,” said the Infant; “but that’s no reason why my vast stores of experience should be lost to posterity.” He was just thirty, and in that same summer an imperious wire drew me to his baronial castle: “Got good haul; ex Tamar. Come along.”

It was an unusually good haul, arranged with a single eye to my benefit. There was a baldish, broken-down captain of Native Infantry, shivering with ague behind an indomitable red nose—and they called him Captain Dickson. There was another captain, also of Native Infantry, with a fair mustache; his face was like white glass, and his hands were fragile, but he answered joyfully to the cry of Tertius. There was an enormously big and well-kept man, who had evidently not campaigned for years, clean-shaved, soft-voiced, and cat-like, but still Abanazar for all that he adorned the Indian Political Service; and there was a lean Irishman, his face tanned blue-black with the suns of the Telegraph Department. Luckily the baize doors of the bachelors’ wing fitted tight, for we dressed promiscuously in the corridor or in each other’s rooms, talking, calling, shouting, and anon waltzing by pairs to songs of Dick Four’s own devising.

There were sixty years of mixed work to be sifted out between us, and since we had met one another from time to time in the quick scene-shifting of India—a dinner, camp, or a race-meeting here; a dak-bungalow or railway station up country somewhere else—we had never quite lost touch. Infant sat on the banisters, hungrily and enviously drinking it in. He enjoyed his baronetcy, but his heart yearned for the old days.

It was a cheerful babel of matters personal, provincial, and imperial, pieces of old callover lists, and new policies, cut short by the roar of a Burmese gong, and we went down not less than a quarter of a mile of stairs to meet Infant’s mother, who had known us all in our school-days and greeted us as if those had ended a week ago. But it was fifteen years since, with tears of laughter, she had lent me a gray princess-skirt for amateur theatricals.

That was a dinner from the “Arabian Nights,” served in an eighty-foot hall full of ancestors and pots of flowering roses, and, what was more impressive, heated by steam. When it was ended and the little mother had gone away—(“You boys want to talk, so I shall say good-night now”)—we gathered about an apple-wood fire, in a gigantic polished steel grate, under a mantelpiece ten feet high, and the Infant compassed us about with curious liqueurs and that kind of cigarette which serves best to introduce your own pipe.

“Oh, bliss!” grunted Dick Four from a sofa, where he had been packed with a rug over him. “First time I’ve been warm since I came home.”

We were all nearly on top of the fire, except Infant, who had been long enough at home to take exercise when he felt chilled. This is a grisly diversion, but much affected by the English of the Island.

“If you say a word about cold tubs and brisk walks,” drawled McTurk, “I’ll kill you, Infant. I’ve got a liver, too. ‘Member when we used to think it a treat to turn out of our beds on a Sunday morning—thermometer fifty-seven degrees if it was summer—and bathe off the Pebbleridge? Ugh!”

“‘Thing I don’t understand,” said Tertius, “was the way we chaps used to go down into the lavatories, boil ourselves pink, and then come up with all our pores open into a young snow-storm or a black frost. Yet none of our chaps died, that I can remember.”

“Talkin’ of baths,” said McTurk, with a chuckle, “‘member our bath in Number Five, Beetle, the night Rabbits-Eggs rocked King? What wouldn’t I give to see old Stalky now! He is the only one of the two Studies not here.”

“Stalky is the great man of his Century,” said Dick Four.

“How d’you know?” I asked.

“How do I know?” said Dick Four, scornfully. “If you’ve ever been in a tight place with Stalky you wouldn’t ask.”

“I haven’t seen him since the camp at Pindi in ‘87,” I said. “He was goin’ strong then—about seven feet high and four feet through.”

“Adequate chap. Infernally adequate,” said Tertius, pulling his mustache and staring into the fire.

“Got dam’ near court-martialed and broke in Egypt in ‘84,” the Infant volunteered. “I went out in the same trooper with him—as raw as he was. Only I showed it, and Stalky didn’t.”

“What was the trouble?” said McTurk, reaching forward absently to twitch my dress-tie into position.

“Oh, nothing. His colonel trusted him to take twenty Tommies out to wash, or groom camels, or something at the back of Suakin, and Stalky got embroiled with Fuzzies five miles in the interior. He conducted a masterly retreat and wiped up eight of ‘em. He knew jolly well he’d no right to go out so far, so he took the initiative and pitched in a letter to his colonel, who was frothing at the mouth, complaining of the ‘paucity of support accorded to him in his operations.’ Gad, it might have been one fat brigadier slangin’ another! Then he went into the Staff Corps.”

“That—is—entirely—Stalky,” said Abanazar from his arm-chair.

“You’ve come across him, too?” I said.

“Oh, yes,” he replied in his softest tones. “I was at the tail of that—that epic. Don’t you chaps know?”

We did not—Infant, McTurk, and I; and we called for information very politely.

“‘Twasn’t anything,” said Tertius. “We got into a mess up in the Khye-Kheen Hills a couple o’ years ago, and Stalky pulled us through. That’s all.”

McTurk gazed at Tertius with all an Irishman’s contempt for the tongue-tied Saxon.

“Heavens!” he said. “And it’s you and your likes govern Ireland. Tertius, aren’t you ashamed?”

“Well, I can’t tell a yarn. I can chip in when the other fellow starts bukhing. Ask him.” He pointed to Dick Four, whose nose gleamed scornfully over the rug.

“I knew you wouldn’t,” said Dick Four. “Give me a whiskey and soda. I’ve been drinking lemon-squash and ammoniated quinine while you chaps were bathin’ in champagne, and my head’s singin’ like a top.”

He wiped his ragged mustache above the drink; and, his teeth chattering in his head, began: “You know the Khye-Kheen-Malo’t expedition, when we scared the souls out of ‘em with a field force they daren’t fight against? Well, both tribes—there was a coalition against us—came in without firing a shot; and a lot of hairy villains, who had no more power over their men than I had, promised and vowed all sorts of things. On that very slender evidence, Pussy dear—”

“I was at Simla,” said Abanazar, hastily.

“Never mind, you’re tarred with the same brush. On the strength of those tuppenny-ha’penny treaties, your asses of Politicals reported the country as pacified, and the Government, being a fool, as usual, began road-makin’—dependin’ on local supply for labor. ‘Member that, Pussy? ‘Rest of our chaps who’d had no look-in during the campaign didn’t think there’d be any more of it, and were anxious to get back to India. But I’d been in two of these little rows before, and I had my suspicions. I engineered myself, summaingenio_, into command of a road-patrol—no shovellin’, only marching up and down genteelly with a guard. They’d withdrawn all the troops they could, but I nucleused about forty Pathans, recruits chiefly, of my regiment, and sat tight at the base-camp while the road-parties went to work, as per Political survey.”

“Had some rippin’ sing-songs in camp, too,” said Tertius.

“My pup”—thus did Dick Four refer to his subaltern—“was a pious little beast. He didn’t like the sing-songs, and so he went down with pneumonia. I rootled round the camp, and found Tertius gassing about as a D.A.Q.M.G., which, God knows, he isn’t cut out for. There were six or eight of the old Coll. at base-camp (we’re always in force for a frontier row), but I’d heard of Tertius as a steady old hack, and I told him he had to shake off his D.A.Q.M.G. breeches and help me. Tertius volunteered like a shot, and we settled it with the authorities, and out we went—forty Pathans, Tertius, and me, looking up the road-parties. Macnamara’s—‘member old Mac, the Sapper, who played the fiddle so damnably at Umballa?—Mac’s party was the last but one. The last was Stalky’s. He was at the head of the road with some of his pet Sikhs. Mac said he believed he was all right.”

“Stalky is a Sikh,” said Tertius. “He takes his men to pray at the Durbar Sahib at Amritzar, regularly as clockwork, when

Comments (0)