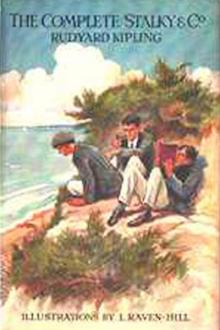

Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗

- Author: Rudyard Kipling

- Performer: -

Book online «Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗». Author Rudyard Kipling

“I didn’t—I wasn’t.”

“We saw you!” said Beetle. “And now—I’ll be decent, Carson—you sneak back with her kisses” (not for nothing had Beetle perused the later poets) “hot on your lips and call prefects’ meetings, which aren’t prefects’ meetings, to uphold the honor of the Sixth.” A new and heaven-cleft path opened before him that instant. “And how do we know,” he shouted—“how do we know how many of the Sixth are mixed up in this abominable affair?”

“Yes, that’s what we want to know,” said McTurk, with simple dignity.

“We meant to come to you about it quietly, Carson, but you would have the meeting,” said Stalky sympathetically.

The Sixth were too taken aback to reply. So, carefully modelling his rhetoric on King, Beetle followed up the attack, surpassing and surprising himself, “It—it isn’t so much the cynical immorality of the biznai, as the blatant indecency of it, that’s so awful. As far as we can see, it’s impossible for us to go into Bideford without runnin’ up against some prefect’s unwholesome amours. There’s nothing to snigger over, Naughten. I don’t pretend to know much about these things—but it seems to me a chap must be pretty far dead in sin” (that was a quotation from the school chaplain) “when he takes to embracing his paramours” (that was Hakluyt) “before all the city” (a reminiscence of Milton). “He might at least have the decency—you’re authorities on decency, I believe—to wait till dark. But he didn’t. You didn’t! Oh, Tulke. You—you incontinent little animal!”

“Here, shut up a minute. What’s all this about, Tulke?” said Carson.

“I—look here. I’m awfully sorry. I never thought Beetle would take this line.”

“Because—you’ve—no decency—you—thought—I hadn’t,” cried Beetle all in one breath.

“Tried to cover it all up with a conspiracy, did you?” said Stalky.

“Direct insult to all three of us,” said McTurk. “A most filthy mind you have, Tulke.”

“I’ll shove you fellows outside the door if you go on like this,” said Carson angrily.

“That proves it’s a conspiracy,” said Stalky, with the air of a virgin martyr.

“I—I was goin’ along the street—I swear I was,” cried Tulke, “and—and I’m awfully sorry about it—a woman came up and kissed me. I swear I didn’t kiss her.”

There was a pause, filled by Stalky’s long, liquid whistle of contempt, amazement, and derision.

“On my honor,” gulped the persecuted one. “Oh, do stop him jawing.”

“Very good,” McTurk interjected. “We are compelled, of course, to accept your statement.”

“Confound it!” roared Naughten. “You aren’t head-prefect here, McTurk.”

“Oh, well,” returned the Irishman, “you know Tulke better than we do. I am only speaking for ourselves. We accept Tulke’s word. But all I can say is that if I’d been collared in a similarly disgustin’ situation, and had offered the same explanation Tulke has, I—I wonder what you’d have said. However, it seems on Tulke’s word of honor—”

“And Tulkus—beg pardon—_kiss_, of course–Tulkiss is an honorable man,” put in Stalky.

“—that the Sixth can’t protect ‘emselves from bein’ kissed when they go for a walk!” cried Beetle, taking up the running with a rush. “Sweet business, isn’t it? Cheerful thing to tell the fags, ain’t it? We aren’t prefects, of course, but we aren’t kissed very much. Don’t think that sort of thing ever enters our heads; does it, Stalky?”

“Oh, no!” said Stalky, turning aside to hide his emotions. McTurk’s face merely expressed lofty contempt and a little weariness.

“Well, you seem to know a lot about it,” interposed a prefect.

“Can’t help it—when you chaps shove it under our noses.” Beetle dropped into a drawling parody of King’s most biting colloquial style—the gentle rain after the thunder-storm. “Well, it’s all very sufficiently vile and disgraceful, isn’t it? I don’t know who comes out of it worst: Tulke, who happens to have been caught; or the other fellows who haven’t. And we—” here he wheeled fiercely on the other two—“we’ve got to stand up and be jawed by them because we’ve disturbed their intrigues.”

“Hang it! I only wanted to give you a word of warning,” said Carson, thereby handing himself bound to the enemy.

“Warn? You?” This with the air of one who finds loathsome gifts in his locker. “Carson, would you be good enough to tell us what conceivable thing there is that you are entitled to warn us about after this exposure? Warn? Oh, it’s a little too much! Let’s go somewhere where it’s clean.”

The door banged behind their outraged innocence.

“Oh, Beetle! Beetle! Beetle! Golden Beetle!” sobbed Stalky, hurling himself on Beetle’s panting bosom as soon as they reached the study. “However did you do it?”

“Dear-r man” said McTurk, embracing Beetle’s head with both arms, while he swayed it to and fro on the neck, in time to this ancient burden—

“Pretty lips—sweeter than—cherry or plum. Always look—jolly and—never look glum; Seem to say—Come away. Kissy!—come, come! Yummy-yum! Yummy-yum! Yummy-yum-yum!”

“Look out. You’ll smash my gig-lamps,” puffed Beetle, emerging. “Wasn’t it glorious? Didn’t I ‘Eric’ ‘em splendidly? Did you spot my cribs from King? Oh, blow!” His countenance clouded. “There’s one adjective I didn’t use—obscene. Don’t know how I forgot that. It’s one of King’s pet ones, too.”

“Never mind. They’ll be sendin’ ambassadors round in half a shake to beg us not to tell the school. It’s a deuced serious business for them,” said McTurk. “Poor Sixth—poor old Sixth!”

“Immoral young rips,” Stalky snorted. “What an example to pure-souled boys like you and me!”

And the Sixth in Carson’s study sat aghast, glowering at Tulke, who was on the edge of tears. “Well,” said the head-prefect acidly. “You’ve made a pretty average ghastly mess of it, Tulke.”

“Why—why didn’t you lick that young devil Beetle before he began jawing?” Tulke wailed.

“I knew there’d be a row,” said a prefect of Prout’s house. “But you would insist on the meeting, Tulke.”

“Yes, and a fat lot of good it’s done us,” said Naughten. “They come in here and jaw our heads off when we ought to be jawin’ them. Beetle talks to us as if we were a lot of blackguards and—and all that. And when they’ve hung us up to dry, they go out and slam the door like a housemaster. All your fault, Tulke.”

“But I didn’t kiss her.”

“You ass! If you’d said you had and stuck to it, it would have been ten times better than what you did,” Naughten retorted. “Now they’ll tell the whole school—and Beetle’ll make up a lot of beastly rhymes and nick-names.”

“But, hang it, she kissed me!” Outside of his work, Tulke’s mind moved slowly.

“I’m not thinking of you. I’m thinking of us. I’ll go up to their study and see if I can make ‘em keep quiet!”

“Tulke’s awf’ly cut up about this business,” Naughten began, ingratiatingly, when he found Beetle.

“Who’s kissed him this time?”

“—and I’ve come to ask you chaps, and especially you, Beetle, not to let the thing be known all over the school. Of course, fellows as senior as you are can easily see why.”

“Um!” said Beetle, with the cold reluctance of one who foresees an unpleasant public duty. “I suppose I must go and talk to the Sixth again.”

“Not the least need, my dear chap, I assure you,” said Naughten hastily. “I’ll take any message you care to send.”

But the chance of supplying the missing adjective was too tempting. So Naughten returned to that still undissolved meeting, Beetle, white, icy, and aloof, at his heels.

“There seems,” he began, with laboriously crisp articulation, “there seems to be a certain amount of uneasiness among you as to the steps we may think fit to take in regard to this last revelation of the—ah—obscene. If it is any consolation to you to know that we have decided—for the honor of the school, you understand—to keep our mouths shut as to these—ah—obscenities, you—ah—have it.”

He wheeled, his head among the stars, and strode statelily back to his study, where Stalky and McTurk lay side by side upon the table wiping their tearful eyes—too weak to move.

The Latin prose paper was a success beyond their wildest dreams. Stalky and McTurk were, of course, out of all examinations (they did extra-tuition with the Head), but Beetle attended with zeal.

“This, I presume, is a par-ergon on your part,” said King, as he dealt out the papers. “One final exhibition ere you are translated to loftier spheres?. A last attack on the classics? It seems to confound you already.”

Beetle studied the print with knit brows. “I can’t make head or tail of it,” he murmured. “What does it mean?”

“No, no!” said King, with scholastic coquetry. “We depend upon you to give us the meaning. This is an examination, Beetle mine, not a guessing-competition. You will find your associates have no difficulty in—”

Tulke left his place and laid the paper on the desk. King looked, read, and turned a ghastly green.

“Stalky’s missing a heap,” thought Beetle. “Wonder hew King’ll get out of it!”

“There seems,” King began with a gulp, “a certain modicum of truth in our Beetle’s remark. I am—er—inclined to believe that the worthy Randall must have dropped this in ferule—if you know what that means. Beetle, you purport to be an editor. Perhaps you can enlighten the form as to formes.”

“What, sir! Whose form! I don’t see that there’s any verb in this sentence at all, an’—an’—the Ode is all different, somehow.”

“I was about to say, before you volunteered your criticism, that an accident must have befallen the paper in type, and that the printer reset it by the light of nature. No—” he held the thing at arm’s length—“our Randall is not an authority on Cicero or Horace.”

“Rather mean to shove it off on Randall,” whispered Beetle to his neighbor. “King must ha’ been as screwed as an owl when he wrote it out.”

“But we can amend the error by dictating it.”

“No, sir.” The answer came pat from a dozen throats at once. “That cuts the time for the exam. Only two hours allowed, sir. ‘Tisn’t fair. It’s a printed-paper exam. How’re we goin’ to be marked for it! It’s all Randall’s fault. It isn’t our fault, anyhow. An exam.‘s an exam.,” etc., etc.

Naturally Mr. King considered this was an attempt to undermine his authority, and, instead of beginning dictation at once, delivered a lecture on the spirit in which examinations should be approached. As the storm subsided, Beetle fanned it afresh.

“Eh? What? What was that you were saying to MacLagan?”

“I only said I thought the papers ought to have been looked at before they were given out, sir.”

“Hear, hear!” from a back bench. Mr. King wished to know whether Beetle took it upon himself personally to conduct the traditions of the school. His zeal for knowledge ate up another fifteen minutes, during which the prefects showed unmistakable signs of boredom.

“Oh, it was a giddy time,” said Beetle, afterwards, in dismantled Number Five. “He gibbered a bit, and I kept him on the gibber, and then he dictated about a half of Dolabella & Co.”

“Good old Dolabella! Friend of mine. Yes?” said Stalky, pensively.

“Then we had to ask him how every other word was spelt, of course, and he gibbered a lot more. He cursed me and MacLagan (Mac played up like a trump) and Randall, and the ‘materialized ignorance of the unscholarly middle classes,’ ‘lust for mere marks,’ and all the rest. It

Comments (0)