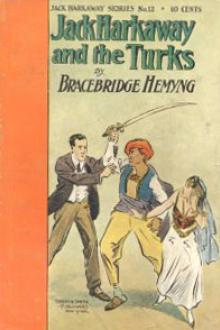

Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks - Bracebridge Hemyng (10 ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Bracebridge Hemyng

- Performer: -

Book online «Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks - Bracebridge Hemyng (10 ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Bracebridge Hemyng

Señor Velasquez walked up to the hotel in which Herbert Murray was staying, and the first person he chanced to meet was Murray himself.

"I wish to have a word with you in private, Señor Murray," said the notary.

Murray looked anxiously around him, starting "like a guilty thing upon a fearful summons."

The bland smile of the Spanish notary reassured him, however.

"What can I do for Señor Velasquez?" he asked.

"I begged for a few words in private," answered Velasquez.

"Take a seat, Señor Velasquez," said Herbert Murray, "and now tell me how I can serve you," after entering his room.

The notary made himself comfortable in his chair.

"I can speak in safety now?" he said.

"Of course."

"No fear of interruption here?"

The notary looked Murray steadily in the eyes as he said—

"I was thinking of your officious servant."

Herbert Murray changed colour as he faltered—

"Of whom?"

"Chivey, I think you call him—your groom, I mean."

"There is no fear from him now," said Murray, with averted eyes; "not the least in the world."

Señor Velasquez smiled significantly.

"Your man Chivey," resumed the Spanish notary, "has confided to me a secret."

"Concerning me?"

"Yes."

"The villain!"

"Now listen to me, Señor Murray. You have behaved very imprudently indeed. Your whole secret is with me."

Herbert started.

"With you?"

"Yes."

Herbert Murray glanced anxiously at the door.

The notary followed his eyes with some inward anxiety, yet he did not betray his uneasiness at all.

"He was speaking the truth for once, then," said Murray. "He had confided his secrets to someone else."

"Yes."

Herbert Murray walked round the room, and took up his position with his back to the door.

"Señor Velasquez," he said, in a low but determined voice, "you have made an unfortunate admission. If there is a witness, it is only one; you are that witness, and your life is in danger."

The notary certainly felt uncomfortable, but he was too old a stager to display it.

Herbert Murray produced a pistol, which he proceeded to examine and to cock deliberately.

"That would not advance your purpose much, Señor Murray," he said, coolly; "the noise would bring all the house trooping into the room."

Murray was quite calm and collected now, and therefore he was open to reason.

"There is something in that," he said, "so I have a quieter helpmate here."

He uncocked the pistol and put it in his breast pocket.

Then he whipped out a long Spanish stiletto.

"There are other reasons against using that."

"And they are?"

"Here is one," returned the notary, drawing a long, slender blade from his sleeve.

Murray was palpably disconcerted at this.

The Spanish notary and the young Englishman stood facing each other in silence for a considerable time.

The former was the first to break the silence.

"Now, look you here, Señor Murray," said he, "I am not a child, nor did I, knowing all I know, come here unprepared for every emergency—aye, even for violence."

"Go on," said Murray, between his set teeth.

"You have imprudently placed yourself in the hands of an unscrupulous young man."

"I have."

"And he has proved himself utterly unworthy?"

"Utterly."

"All of that is known to me," said the notary, craftily. "Now you must pay no heed to this Chivey."

"I will not," returned Herbert Murray, significantly, "though there is little fear of further molestation from him, señor."

Young Murray little dreamt of the cause of the notary's peculiar smile.

"Your sole danger, as I take it, Señor Murray, is from your fellow countryman, Jack Harkaway."

"Yes."

"Then to him you must direct your attention. Where is he?"

"Gone."

"Where to?"

"Don't know."

"I do then," returned the notary, quietly: "and it is to tell you that that I am here. I have all the necessary information; you must follow him."

"Why?"

"To make sure of him," coldly replied the Spaniard.

"How?"

Velasquez spoke not.

But his meaning was just as clear as if he had put it into words.

A vicious dig with his stiletto at the air.

Nothing more.

And so they began to understand each other.

Señor Velasquez, the notary, was playing a double game.

From Herbert Murray he carefully kept the knowledge that Chivey still lived.

And why?

That knowledge would have lessened his hold.

The cunning way in which he let Herbert Murray understand that he knew all, even to the attempt upon Chivey's life at the gravel pits, completed the mastery in which he meant to hold the young rascal.

He arranged everything for young Murray.

He discovered from him the destination of the ship in which Jack Harkaway and his friends had escaped, and he procured him a berth on a vessel sailing in the same direction.

"Once you get within arm's length of this young Harkaway," he said; "you must be firm and let your blow be sure."

"I will," returned his pupil.

"Once Harkaway is removed from your path, you may sleep in peace, for he alone can now punish you for forgery."

"I hope so."

"I know it," said Velasquez.

So well were the notary's plans laid, and so luckily did fortune play into his hands, that forty-eight hours after his interview with Murray, he had that young gentleman safely on board a ship outward bound.

Now Herbert Murray had passed but one night after that fearful scene by the gravel pit, but the remembrance of it haunted his pillow from the moment he went to bed to the moment he arose unrefreshed and full of fever.

And yet he was setting out with the intention of securing his future peace and immunity from peril by the commission of a fresh crime.

The ship was setting sail at a little after daybreak, and it had been arranged that Señor Velasquez was to come and see him off.

But much to his surprise, the notary did not put in an appearance.

Eagerly he waited for the ship to start, lest any thing should occur at the eleventh hour, and he should find himself laid by the heels to answer for his crimes.

Chivey was supposed to be hiding.

In reality he was a prisoner in the house of Señor Velasquez, and he knew it.

The notary was an old man, and he suffered from sundry ailments which belong to age—notably to rheumatism.

An acute attack prostrated the old man, and held him down when he was most anxious to be up and doing.

And the night before Herbert Murray was to set sail, he lay groaning and moaning with racking pains.

His cries reached Chivey, who lay in the next room, and he came to the sick man's door to ask if he could be of any assistance.

He peered warily in.

In spite of his groans and anguish, the old notary was insensible under the influence of an opiate.

Chivey crept in.

On a low table beside the bed was a lamp flickering fearfully, and a glass containing some medicine.

Beside the glass a phial labelled laudanum.

Something possessed the intruder to empty the contents of the phial into the glass, and just as he had done so, the sufferer opened his eyes.

"Who's there?"

"It's me, Señor Velasquez," said the tiger. "You have been ill——"

"What do you do here?" demanded the notary, sharply.

"You called out. I thought I might be of assistance."

"No, no."

"Then I will go, señor," said Chivey, "for I am tired."

"Stay, give me my physic before you go."

Chivey handed him the glass.

The sick man gulped it down, and made a wry face.

"How bitter it tastes," he said, with a shudder.

"Good-night, señor."

"Good-night."

Chivey did not remain very long absent.

The heavy breathing of the notary soon told him that it was safe to return to the room.

The business of the morrow so filled the mind of the old Spaniard, that he was talking of it in his sleep.

"At an hour after daybreak, I tell you, Murray," he muttered. "The berth is paid for, paid for by my gold. You follow on the track of your enemy Harkaway, and once you are within reach, give a sharp, sure stroke, and you will be free from your only enemy, seeing that you have already taken good care of your traitor servant."

Chivey was amazed, electrified.

Did he hear aright?

"At daybreak!" he exclaimed, aloud.

"Yes; at daybreak," returned the notary in his sleep.

After a pause, the sleeper muttered—

"What say you? If Chivey were not quite dead? What of that? How could he follow you? He has no funds. The only money he possessed I have now in my strong box under my bed."

Chivey was staggered.

"Is Murray going to bolt, and leave me in the power of this old villain, I wonder," he muttered.

He broke off in his speculations, for the notary was babbling something again.

"'The Mogador,'" muttered the old man, speaking more thickly than before as the opiate began to make itself felt; "the captain is called Gonzales. You have only to mention the name of Señor Velasquez, and he will treat you well. He knows me."

He muttered a few more words which grew more and more incoherent each instant.

Then he lay back motionless as a log.

The opium held him fast in its power.

"Now for the box," exclaimed the tiger, excitedly.

Chivey tore open the box, and lifting up some musty old deeds and parchments, he feasted his eyes upon a mine of wealth.

A pile of gold.

Bright glittering pieces of every size and country.

And beside it thick bundles of paper money.

"Gold is uncommonly pretty," said the tiger, "but the notes packs the closest."

Bundle after bundle he stowed away about his person, regularly padding his chest under his shirt.

"Now for a trifle of loose cash," he said, coolly.

So saying, he dropped about sixty or seventy gold pieces into his breeches pocket.

His waistcoat pockets he stuffed full also.

Then he pushed back the box into its place under the bed.

"The old man still sleeps," he said to himself, looking round at the bed.

He was in a rare good humour with himself.

"Ha, ha! I am rich now," said Chivey. "Thank you, old señor, you have done me a good turn. May you sleep long."

He gave a final glance about him and made off.

A distant church clock tolled the hour of midnight as he gained the seashore.

He was in luck.

Not a soul did he encounter until he reached the beach, when he came upon two sailors, launching a rowing boat.

"'Mogador?'" he said, in a tone of inquiry.

"Si, señor."

"That's your sort," said Chivey. "I want to see Captain Gonzales."

"Come with us, then," said one of the sailors.

"Rather," responded the tiger; "off we dive; whip 'em up, tickle him under the flank, and we're there in a common canter."

The sailors both understood a little of English.

In very little time they were standing on the deck of the "Mogador."

And facing Chivey as he scrambled up the side, was the master of the ship, Captain Gonzales, to whom Chivey was presented at once by one of the sailors.

"Señor Velasquez has sent me to you, captain," said the ever ready tiger.

"Then you are welcome."

"He told me to give you that," said Chivey, handing the captain a pair of banknotes; "and to beg you to give me the best of accommodation in a cabin all to myself."

"It shall be done."

"And above all not to let Mr. Murray know of my presence on board when he comes."

"Good."

"I am going on very important business for Señor Velasquez, captain," pursued Chivey, with infinite assurance; "as you may judge, for he values your care of me at one hundred crowns to be paid on your next visit here."

"Rely upon my uttermost assistance."

"Thank you," said Chivey, with a patronising smile; "and now I'll be obliged to you to show me to my berth."

"Here," cried the Spanish captain. "Pedro—Juan—Lopez. Take this gentleman to my private cabin."

The "Mogador" stood out to sea bravely enough.

Chivey was there.

Herbert Murray was there.

But the latter little suspected the presence of the former.

Herbert Murray, in fancied security, was reclining on deck upon some cushions he had got up from below, smoking lazily, and looking up at the blue sky overhead, when Chivey, who had been looking vainly out for an appropriate cue to make his reappearance, slipped suddenly forward, and touching his hat, remarked in the coolest manner in the world—

"Did you ring for me, sir?"

Herbert looked up just as if he had seen a ghost.

"Chivey!"

"Guv'ner."

Herbert Murray stared at his villainous servant.

But villainous as Chivey was, Herbert Murray never

Comments (0)