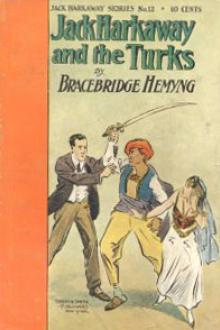

Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks - Bracebridge Hemyng (10 ebook reader .txt) 📗

- Author: Bracebridge Hemyng

- Performer: -

Book online «Jack Harkaway's Boy Tinker Among The Turks - Bracebridge Hemyng (10 ebook reader .txt) 📗». Author Bracebridge Hemyng

His friends grew anxious.

They wished him to take medical advice.

He resisted all persuasion stoutly.

So they had recourse to artifice, and invited an eminent medical man to their house as a visitor.

And then under the guise of a friendly chat, the doctor took his observations.

But the peculiar ailment, if ailment it could be called, of Isaac Mole, completely baffled the man of science at first.

It was only in a casual conversation that, being an observing man, he discovered the real truth.

"Our patient wants a roving commission," said the physician to himself.

And then he communicated his own convictions to old Jack.

"I scarcely believe it possible, doctor," said Jack.

But the doctor was positive.

"Nothing will do him any good but to get on the move; I'm as sure of that as I am that he has no physical ailment."

"What's to be done then?" demanded Harkaway. "He can't travel alone."

"I don't know that," said the doctor; "he's hale and wiry enough. The only difficulty that I can see, is Mrs. Mole."

"I'll undertake to get over that," said Jack.

"You will?"

"Yes."

"It is settled then," said the physician, with a smile.

"Good."

"What would do him more good than all the physic in the world, would be to send him after your son."

"My Jack!"

"Yes."

"Impossible. Why, Jack is en route for Turkey."

"What of that?" coolly inquired the doctor.

"Consider the distance, my dear doctor."

"Pshaw, sir. Distance is nothing nowadays. It was a very different thing when I was a boy. Take my word for it, Mr. Harkaway, our patient will jump at the chance."

"He's very much attached to my roving boy."

"I know it," returned the doctor. "Never a day passes but he speaks of him; I declare that I never had a single interview with Mr. Mole, but that he has managed somehow to turn the conversation upon your son and his pranks."

"Oh, Jack, he has played him some dreadful tricks."

"Yes," returned the physician dryly, "and so has Jack's father, by all accounts."

"Ahem!"

"And yet I really believe that he enjoys the recollection of the boy's infamous practical jokes."

"I believe you are right," responded Harkaway.

A day or two later on the doctor was seated with Mr. Mole.

"Mr. Mole."

"Doctor."

"Your health must be looked to. You'll have to travel."

"How, doctor?" said Mole.

"Young Harkaway is in foreign parts, and his prolonged absence causes his parents considerable uneasiness, and you must go and look after him."

Mole's eyes twinkled.

"Do you mean it?"

"I do. When would you like to start?"

"To-day."

"Very good. The sooner the better," said the doctor.

Mr. Mole's countenance fell suddenly.

An ugly thought crossed him.

What would Mrs. Mole say?

"There is one matter I would like to consult you on, doctor."

"What might that be?" demanded the doctor.

"My wife might have a word to say upon the subject."

"I will undertake to remove her scruples," said the doctor.

"You will?"

"Yes. She will never object when she knows how important your mission is."

"Doctor," exclaimed Mr. Mole, joyously; "you are a trump."

A delay naturally occurred, however.

Mr. Mole could not travel with his wooden stumps, his friends one and all agreed.

No.

He must have a pair of cork legs made.

The doctor who had been attending our old friend knew of a maker of artificial limbs who was a wonderful man, according to all accounts.

"Yes," said Mole, "cork legs well hosed will——"

At this moment a voice tuning up under the window cut him short,

"He gave his own leg to the undertaker,

And sent for a skilful cork-leg maker.

Ritooral looral."

"That's Dick Harvey. Infamous!" ejaculated Mr. Mole.

"On a brace of broomsticks never I'll walk,

But I'll have symmetrical limbs of cork.

Ritooral looral."

"Monstrous!" exclaimed Mr. Mole; "close the window, sir, if you please."

It was all very well to say "Close it," but this was easier said than done.

Dick Harvey had fixed it beyond the skill of that skilful mechanician to unfasten.

The aggravating minstrel continued without—

"Than timber this cork is better by half,

Examine likewise my elegant calf.

Ritooral looral——"

"I will have that window closed," cried Mole.

He arose, forgetting in his haste that he was minus one leg, and down he rolled.

The artificial limb-maker lunged after him, and succeeded with infinite difficulty in getting him on to his feet again.

"Dear, dear!" said Mr. Mole. "No matter, I can manage it."

He picked up the nearest object to hand, and hurled it out of window.

CHAPTER LXV.

HOW THE ORPHAN BECAME POSSESSED OF A FLUTE.

But we must leave Mole for a time, and return to our friends on their travels.

When next they landed at a Turkish town, Mr. Figgins went to a different hotel to that patronised by young Jack, whose practical joking was rather too much for the orphan.

But they found him out, and paid him a visit one morning.

After the first greeting, Mr. Figgins was observed to be unusually thoughtful.

At length, after a long silence he exclaimed—

"I can't account for it, I really can't."

"What can't you account for, Mr. Figgins?" asked young Jack.

"The strange manners of the people of this country," answered the orphan.

"Of what is it you have to complain particularly?" inquired Jack.

"Well, it's this; wherever I go, I seem to be quite an object of curiosity."

"Of interest you mean, Mr. Figgins," returned Jack, winking at Harry Girdwood; "you are an Englishman, you know, and Englishmen are always very interesting to foreigners."

"I can't say as to that," the orphan replied; "I only know I can't show my nose out of doors without being pointed at."

"Ah, yes. You excite interest the moment you make your appearance."

"Then, if I walk in the streets, dark swarthy men stare at me and follow me till I have quite a crowd at my heels."

"Another proof of the interest they take in you."

"Well, I don't like it at all," said the orphan, fretfully; "and then the dogs bark at me in a very distressing manner."

"It's the only way they have of bidding you welcome," remarked Harry Girdwood.

"I wish they wouldn't take any notice of me at all; it's a nuisance."

"Perhaps you'd like them to leave off barking, and take to biting?"

"No, it's just what I shouldn't like, but it's what I'm constantly afraid they will do," wailed the poor orphan.

There was a slight pause, during which young Jack and his comrade grinned quietly at each other, and presently the former said—

"I think I can account for all this."

"Can you?" asked Mr. Figgins. "How?"

"It all lies in the dress you wear."

"In the dress?"

"Yes; you are in a Turkish country, and although I admit you look well in your splendid new tourist suit, cross-barred all over in four colours, I fancy it would be better if you dressed as a Turk during your stay here."

"A Turk, Jack?"

"Yes; now, if you were to have your head shaved, and dress yourself like a Turk," said Jack, "all this wonderment would cease, and you would go out, and come in, without exciting any remark."

Mr. Figgins fell back in his chair.

"Ha-ha-have my head sha-a-ved, dress myself up li-like a Turk?" he gasped. "You surely don't mean that?"

"I do, indeed," replied Jack, seriously.

"What? Wear baggy breeches, and an enormous turban, and slippers turned up at the toes! What would the natives say?"

"Why, they'd say you were a very sensible individual," remarked Harry. "Don't you remember the old saying?—'When you're in Turkey, you must do as Turkey does.'"

Mr. Figgins reflected for a moment.

"And you really think if I were to go in, for a regular Turkish fit-out, I should be allowed to enjoy my walks in peace?" he asked, at length.

"Decidedly," answered his counsellors, with the utmost gravity.

"Then I'll take your advice, and be a Turk until further notice," said the orphan; "but there's one thing still."

"What's that?"

"My complexion isn't near dark enough for one of these infidels."

"Oh, that won't matter," said Jack; "only slip into the Turkish togs. Go in for any quantity of turban, and they won't care a button about your complexion."

"Very well, then, that's settled; I'll turn Turk at once. But must I have my head shaved?"

"That's important," said Jack.

Having made up his mind on that point, the orphan at once put on his hat, and taking a sip of brandy to compose his nerves, he sallied forth, directing his steps to the nearest barber's.

On his way thither he attracted the usual amount of attention, and when he reached the barber's shop, he found himself accompanied by a select crowd of deriding Turks, and a dozen or so of yelping curs, shouting and barking in concert.

The barber received him with the extreme of Eastern courtesy.

"What does the English signor require at the hands of the humblest of his slaves?" was the deferential inquiry.

"I have a fancy to turn Turk, and I want my head shaved," explained Mr. Figgins, nervously; "pray be careful, since I'm only a poor orphan, who——"

Before he had time to finish his sentence, he found himself wedged into a chair with a towel under his chin.

The next moment his head, under the energetic manipulation of the operator, was a creamy mass of lather.

"Be sure and don't cut my head off," murmured the orphan, as he watched the razor flashing to and fro along the strop.

"Your servant will not disturb the minutest pimple," said the barber.

With wonderful celerity, the artist went to work.

In less than two minutes the cranium of Mark Antony Figgins was as smooth and destitute of hair as a bladder of lard.

Then followed the process of shampooing, which was very soothing to the orphan's feelings.

At length, the operation being completed, the barber bade the orphan put on his hat—which from the loss of his hair went over his eyes and rested on his nose—and left the shop.

His friends—the mob and the dogs—had waited for him outside very patiently.

If his appearance had been interesting before, their interest was now greatly increased.

A loud shout welcomed him, and he proceeded along the street under difficulties, holding his hat in one hand, with the crowd at his heels.

Straight to the bazaar he went.

Here he found a venerable old Turkish Jew, who seemed to divine by instinct what he wanted.

"Closhe, shignor, closhe," he cried in broken English. "Shtep in and take your choice."

Before the bewildered orphan knew where he was, he found himself in the interior of Ibrahim's emporium.

Here a profusion of garments were displayed before his eyes.

Having no preference for any particular colour, he took what the Jew pressed upon him.

In a short time his costume was complete, consisting of a pair of ample white trousers, and a blue shirt, surmounted by a crimson vest, secured at the waist by a purple sash, and on his feet a pair of yellow slippers of Morocco leather.

The turban alone was wanting.

"Be sure and let me have a good big turban," urged Mr. Figgins.

Ibrahim assured him that he should have one as big as he could carry, and he kept his word.

Unrolling a great many yards of stuff, he formed a turban of enormous dimensions of green and yellow stripe, which he placed upon the head of his customer.

"Shall I do? Do I look like a native Turk?" asked the latter, after he had put on his things.

"Do?" echoed the Jew, exultingly. "If it ish true dat de closhe makes de man, you vill do excellent vell, and de people vill not now run after you."

Mr. Figgins having settled his account with the Hebrew clothier, and paid just three times as much as he ought to have done, went out again with considerable confidence, looking as gaudy in his mixture of bright colours as a macaw.

"No one will dare to jeer at me now," he persuaded himself.

But he was mistaken.

Hardly had he taken a half dozen steps when his brilliant costume attracted great notice.

"What a splendid Turk!" cried some.

"Who is that magnificent bashaw?" asked others, as he strutted past.

No one knew, and upon a nearer examination it was seen that the "splendid Turk" and "magnificent bashaw" was no Turk at all.

Indignation seized upon those who had a moment before been filled with admiration.

"Impostor, unbelieving dog!" shouted the enraged populace. "He is an accursed Giaour, in the dress of a follower of the Prophet."

At this, a fierce

Comments (0)