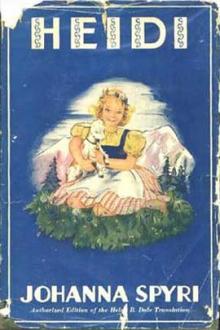

Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗

- Author: Johanna Spyri

- Performer: 0753454947

Book online «Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗». Author Johanna Spyri

like to tell you herself how grateful she is; I do not know who

else would have done it for us; we shall not forget your

kindness, for I am sure—”

“That will do,” said the old man, interrupting her.

“I know what you think of Alm-Uncle without your telling me. Go

indoors again, I can find out for myself where the mending is

wanted.”

Brigitta obeyed on the spot, for Uncle had a way with him that

made few people care to oppose his will. He went on knocking

with his hammer all round the house, and then mounted the narrow

steps to the roof, and hammered away there, until he had used up

all the nails he had brought with him. Meanwhile it had been

growing dark, and he had hardly come down from the roof and

dragged the sleigh out from behind the goat-shed when Heidi

appeared outside. The grandfather wrapped her up and took her in

his arms as he had done the day before, for although he had to

drag the sleigh up the mountain after him, he feared that if the

child sat in it alone her wrappings would fall off and that she

would be nearly if not quite frozen, so he carried her warm and

safe in his arms.

So the winter went by. After many years of joyless life, the

blind grandmother had at last found something to make her happy;

her days were no longer passed in weariness and darkness, one

like the other without pleasure or change, for now she had

always something to which she could look forward. She listened

for the little tripping footstep as soon as day had come, and

when she heard the door open and knew the child was really there,

she would call out, “God be thanked, she has come again!” And

Heidi would sit by her and talk and tell her everything she knew

in so lively a manner that the grandmother never noticed how the

time went by, and never now as formerly asked Brigitta, “Isn’t

the day done yet?” but as the child shut the door behind her on

leaving, would exclaim, “How short the afternoon has seemed;

don’t you think so, Brigitta?” And this one would answer, “I do

indeed; it seems as if I had only just cleared away the mid-day

meal.” And the grandmother would continue, “Pray God the child is

not taken from me, and that Alm-Uncle continues to let her come!

Does she look well and strong, Brigitta?” And the latter would

answer, “She looks as bright and rosy as an apple.”

And Heidi had also grown very fond of the old grandmother, and

when at last she knew for certain that no one could make it

light for her again, she was overcome with sorrow; but the

grandmother told her again that she felt the darkness much less

when Heidi was with her, and so every fine winter’s day the child

came travelling down in her sleigh. The grandfather always took

her, never raising any objection, indeed he always carried the

hammer and sundry other things down in the sleigh with him, and

many an afternoon was spent by him in making the goatherd’s

cottage sound and tight. It no longer groaned and rattled the

whole night through, and the grandmother, who for many winters

had not been able to sleep in peace as she did now, said she

should never forget what the Uncle had done for her.

CHAPTER V. TWO VISITS AND WHAT CAME OF THEM

Quickly the winter passed, and still more quickly the bright

glad summer, and now another winter was drawing to its close.

Heidi was still as lighthearted and happy as the birds, and

looked forward with more delight each day to the coming spring,

when the warm south wind would roar through the fir trees and

blow away the snow, and the warm sun would entice the blue and

yellow flowers to show their heads, and the long days out on the

mountain would come again, which seemed to Heidi the greatest

joy that the earth could give. Heidi was now in her eighth year;

she had learnt all kinds of useful things from her grandfather;

she knew how to look after the goats as well as any one, and

Little Swan and Bear would follow her like two faithful dogs, and

give a loud bleat of pleasure when they heard her voice. Twice

during the course of this last winter Peter had brought up a

message from the schoolmaster at Dorfli, who sent word to Alm-Uncle that he ought to send Heidi to school, as she was over the

usual age, and ought indeed to have gone the winter before. Uncle

had sent word back each time that the schoolmaster would find him

at home if he had anything he wished to say to him, but that he

did not intend to send Heidi to school, and Peter had faithfully

delivered his message.

When the March sun had melted the snow on the mountain side and

the snowdrops were peeping out all over the valley, and the fir

trees had shaken off their burden of snow and were again merrily

waving their branches in the air, Heidi ran backwards and

forwards with delight first to the goat-shed then to the fir-trees, and then to the hut-door, in order to let her grandfather

know how much larger a piece of green there was under the trees,

and then would run off to look again, for she could hardly wait

till everything was green and the full beautiful summer had

clothed the mountain with grass and flowers. As Heidi was thus

running about one sunny March morning, and had just jumped over

the water-trough for the tenth time at least, she nearly fell

backwards into it with fright, for there in front of her, looking

gravely at her, stood an old gentleman dressed in black. When he

saw how startled she was, he said in a kind voice, “Don’t be

afraid of me, for I am very fond of children. Shake hands! You

must be the Heidi I have heard of; where is your grandfather?”

“He is sitting by the table, making round wooden spoons,” Heidi

informed him, as she opened the door.

He was the old village pastor from Dorfli who had been a

neighbor of Uncle’s when he lived down there, and had known him

well. He stepped inside the hut, and going up to the old man, who

was bending over his work, said, “Good-morning, neighbor.”

The grandfather looked up in surprise, and then rising said,

“Good-morning” in return. He pushed his chair towards the

visitor as he continued, “If you do not mind a wooden seat there

is one for you.”

The pastor sat down. “It is a long time since I have seen you,

neighbor,” he said.

“Or I you,” was the answer.

“I have come to-day to talk over something with you,” continued

the pastor. “I think you know already what it is that has

brought me here,” and as he spoke he looked towards the child who

was standing at the door, gazing with interest and surprise at

the stranger.

“Heidi, go off to the goats,” said her grandfather. “You take

them a little salt and stay with them till I come.”

Heidi vanished on the spot.

“The child ought to have been at school a year ago, and most

certainly this last winter,” said the pastor. “The schoolmaster

sent you word about it, but you gave him no answer. What are you

thinking of doing with the child, neighbor?”

“I am thinking of not sending her to school,” was the answer.

The visitor, surprised, looked across at the old man, who was

sitting on his bench with his arms crossed and a determined

expression about his whole person.

“How are you going to let her grow up then?” he asked.

“I am going to let her grow up and be happy among the goats and

birds; with them she is safe, and will learn nothing evil.”

“But the child is not a goat or a bird, she is a human being. If

she learns no evil from these comrades of hers, she will at the

same time learn nothing; but she ought not to grow up in

ignorance, and it is time she began her lessons. I have come now

that you may have leisure to think over it, and to arrange about

it during the summer. This is the last winter that she must be

allowed to run wild; next winter she must come regularly to

school every day.”

“She will do no such thing,” said the old man with calm

determination.

“Do you mean that by no persuasion can you be brought to see

reason, and that you intend to stick obstinately to your

decision?” said the pastor, growing somewhat angry. “You have

been about the world, and must have seen and learnt much, and I

should have given you credit for more sense, neighbor.”

“Indeed,” replied the old man, and there was a tone in his voice

that betrayed a growing irritation on his part too, “and does

the worthy pastor really mean that he would wish me next winter

to send a young child like that some miles down the mountain on

ice-cold mornings through storm and snow, and let her return at

night when the wind is raging, when even one like ourselves

would run a risk of being blown down by it and buried in the

snow? And perhaps he may not have forgotten the child’s mother,

Adelaide? She was a sleep-walker, and had fits. Might not the

child be attacked in the same way if obliged to over-exert

herself? And some one thinks they can come and force me to send

her? I will go before all the courts of justice in the country,

and then we shall see who will force me to do it!”

“You are quite right, neighbor,” said the pastor in a friendly

tone of voice. “I see it would have been impossible to send the

child to school from here. But I perceive that the child is dear

to you; for her sake do what you ought to have done long ago:

come down into Dorfli and live again among your fellowmen. What

sort of a life is this you lead, alone, and with bitter thoughts

towards God and man! If anything were to happen to you up here

who would there be to help you? I cannot think but what you must

be half-frozen to death in this hut in the winter, and I do not

know how the child lives through it!”

“The child has young blood in her veins and a good roof over her

head, and let me further tell the pastor, that I know where wood

is to be found, and when is the proper time to fetch it; the

pastor can go and look inside my wood-shed; the fire is never

out in my hut the whole winter through. As to going to live below

that is far from my thoughts; the people despise me and I them;

it is therefore best for all of us that we live apart.”

“No, no, it is not best for you; I know what it is you lack,”

said the pastor in an earnest voice. “As to the people down

there looking on you with dislike, it is not as bad as you think.

Believe me, neighbor; seek to make your peace with God, pray for

forgiveness where you need it, and then come and see how

differently people will look upon you, and how happy you may yet

be.”

The

Comments (0)