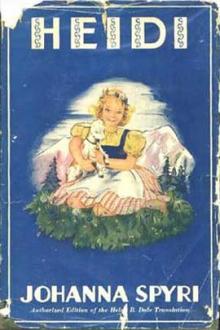

Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗

- Author: Johanna Spyri

- Performer: 0753454947

Book online «Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗». Author Johanna Spyri

HEIDI

by JOHANNA SPYRI

CONTENTS

I Up the Mountain to Alm-Uncle

II At Home with Grandfather

III Out

with the Goats

IV The Visit to Grandmother

V Two Visits and What

Came of Them

VI A New Chapter about New Things

VII Fraulein

Rottenmeier Spends an Uncomfortable Day

VIII There is Great

Commotion in the Large House

IX Herr Sesemann Hears of Things

that are New to Him

X Another Grandmother

XI Heidi Gains in One

Way and Loses in Another

XII A Ghost in the House

XIII A Summer

Evening on the Mountain

XIV Sunday Bells

XV Preparations for a

Journey

XVI A Visitor

XVII A Compensation

XVIII Winter in Dorfli

XIX

The Winter Continues

XX News from Distant Friends

XXI How Life

went on at Grandfather’s

XXII Something Unexpected Happens

XXIII

“Good-bye Till We Meet Again”

INTRODUCTION“Heidi” is a delightful story for children of life in the Alps,

one of many tales written by the Swiss authoress, Johanna Spyri,

who died in her home at Zurich in 1891. She had been well known

to the younger readers of her own country since 1880, when she

published her story, Heimathlos, which ran into three or more

editions, and which, like her other books, as she states on the

title page, was written for those who love children, as well as

for the youngsters themselves. Her own sympathy with the

instincts and longings of the child’s heart is shown in her

picture of Heidi. The record of the early life of this Swiss

child amid the beauties of her passionately loved mountain-home

and during her exile in the great town has been for many years a

favorite book of younger readers in Germany and America.

Madame Spyri, like Hans Andersen, had by temperament a peculiar

skill in writing the simple histories of an innocent world. In

all her stories she shows an underlying desire to preserve

children alike from misunderstanding and the mistaken kindness

that frequently hinder the happiness and natural development of

their lives and characters. The authoress, as we feel in reading

her tales, lived among the scenes and people she describes, and

the setting of her stories has the charm of the mountain scenery

amid which she places her small actors.

Her chief works, besides Heidi, were:— Am Sonntag; Arthur und

Squirrel; Aus dem Leben; Aus den Schweizer Bergen; Aus Nah und

Fern; Aus unserem, Lande; Cornelli wird erzogen; Einer vom Hause

Lesa; 10 Geschichten fur Yung und Alt; Kurze Geschichten, 2

vols.; Gritli’s Kinder, 2 vols.; Heimathlos; Im Tilonethal; In

Leuchtensa; Keiner zu Klein Helfer zu sein; Onkel Titus; Schloss

Wildenstein; Sina; Ein Goldener Spruch; Die Hauffer Muhle;

Verschollen, nicht vergessen; Was soll deim aus ihr werden; Was

aus ihr Geworden ist. M.E.

HEIDI

CHAPTER I. UP THE MOUNTAIN TO ALM-UNCLE

From the old and pleasantly situated village of Mayenfeld, a

footpath winds through green and shady meadows to the foot of

the mountains, which on this side look down from their stern and

lofty heights upon the valley below. The land grows gradually

wilder as the path ascends, and the climber has not gone far

before he begins to inhale the fragrance of the short grass and

sturdy mountain-plants, for the way is steep and leads directly

up to the summits above.

On a clear sunny morning in June two figures might be seen

climbing the narrow mountain path; one, a tall strong-looking

girl, the other a child whom she was leading by the hand, and

whose little checks were so aglow with heat that the crimson

color could be seen even through the dark, sunburnt skin. And

this was hardly to be wondered at, for in spite of the hot June

sun the child was clothed as if to keep off the bitterest frost.

She did not look more than five years old, if as much, but what

her natural figure was like, it would have been hard to say, for

she had apparently two, if not three dresses, one above the

other, and over these a thick red woollen shawl wound round

about her, so that the little body presented a shapeless

appearance, as, with its small feet shod in thick, nailed

mountain-shoes, it slowly and laboriously plodded its way up in

the heat. The two must have left the valley a good hour’s walk

behind them, when they came to the hamlet known as Dorfli, which

is situated half-way up the mountain. Here the wayfarers met with

greetings from all sides, some calling to them from windows, some

from open doors, others from outside, for the elder girl was now

in her old home. She did not, however, pause in her walk to

respond to her friends’ welcoming cries and questions, but passed

on without stopping for a moment until she reached the last of

the scattered houses of the hamlet. Here a voice called to her

from the door: “Wait a moment, Dete; if you are going up higher,

I will come with you.”

The girl thus addressed stood still, and the child immediately

let go her hand and seated herself on the ground.

“Are you tired, Heidi?” asked her companion.

“No, I am hot,” answered the child.

“We shall soon get to the top now. - You must walk bravely on a

little longer, and take good long steps, and in another hour we

shall be there,” said Dete in an encouraging voice.

They were now joined by a stout, good-natured-looking woman, who

walked on ahead with her old acquaintance, the two breaking

forth at once into lively conversation about everybody and

everything in Dorfli and its surroundings, while the child

wandered behind them.

“And where are you off to with the child?” asked the one who had

just joined the party. “I suppose it is the child your sister

left?”

“Yes,” answered Dete. “I am taking her up to Uncle, where she

must stay.”

“The child stay up there with Alm-Uncle! You must be out of your

senses, Dete! How can you think of such a thing! The old man,

however, will soon send you and your proposal packing off home

again!”

“He cannot very well do that, seeing that he is her grandfather.

He must do something for her. I have had the charge of the child

till now, and I can tell you, Barbel, I am not going to give up

the chance which has just fallen to me of getting a good place,

for her sake. It is for the grandfather now to do his duty by

her.”

“That would be all very well if he were like other people,”

asseverated stout Barbel warmly, “but you know what he is. And

what can he do with a child, especially with one so young! The

child cannot possibly live with him. But where are you thinking

of going yourself?”

“To Frankfurt, where an extra good place awaits me,” answered

Dete. “The people I am going to were down at the Baths last

summer, and it was part of my duty to attend upon their rooms.

They would have liked then to take me away with them, but I

could not leave. Now they are there again and have repeated their

offer, and I intend to go with them, you may make up your mind

to that!”

“I am glad I am not the child!” exclaimed Barbel, with a gesture

of horrified pity. “Not a creature knows anything about the old

man up there! He will have nothing to do with anybody, and never

sets his foot inside a church from one year’s end to another.

When he does come down once in a while, everybody clears out of

the way of him and his big stick. The mere sight of him, with

his bushy grey eyebrows and his immense beard, is alarming

enough. He looks like any old heathen or Indian, and few would

care to meet him alone.”

“Well, and what of that?” said Dete, in a defiant voice, “he is

the grandfather all the same, and must look after the child. He

is not likely to do her any harm, and if he does, he will be

answerable for it, not I.”

“I should very much like to know,” continued Barbel, in an

inquiring tone of voice, “what the old man has on his conscience

that he looks as he does, and lives up there on the mountain

like a hermit, hardly ever allowing himself to be seen. All kinds

of things are said about him. You, Dete, however, must certainly

have learnt a good deal concerning him from your sister—am I

not right?”

“You are right, I did, but I am not going to repeat what I

heard; if it should come to his ears I should get into trouble

about it.”

Now Barbel had for long past been most anxious to ascertain

particulars about Alm-Uncle, as she could not understand why he

seemed to feel such hatred towards his fellow-creatures, and

insisted on living all alone, or why people spoke about him half

in whispers, as if afraid to say anything against him, and yet

unwilling to take his Part. Moreover, Barbel was in ignorance as

to why all the people in Dorfli called him Alm-Uncle, for he

could not possibly be uncle to everybody living there. As,

however, it was the custom, she did like the rest and called the

old man Uncle. Barbel had only lived in Dorfli since her

marriage, which had taken place not long before. Previous to

that her home had been below in Prattigau, so that she was not

well acquainted with all the events that had ever taken place,

and with all the people who had ever lived in Dorfli and its

neighborhood. Dete, on the contrary, had been born in Dorfli,

and had lived there with her mother until the death of the latter

the year before, and had then gone over to the Baths at Ragatz

and taken service in the large hotel there as chambermaid. On the

morning of this day she had come all the way from Ragatz with

the child, a friend having given them a lift in a hay-cart as far

as Mayenfeld. Barbel was therefore determined not to lose this

good opportunity of satisfying her curiosity. She put her arm

through Dete’s in a confidential sort of way, and said: “I know I

can find out the real truth from you, and the meaning of all

these tales that are afloat about him. I believe you know the

whole story. Now do just tell me what is wrong with the old man,

and if he was always shunned as he is now, and was always such a

misanthrope.”

“How can I possibly tell you whether he was always the same,

seeing I am only six-and-twenty and he at least seventy years of

age; so you can hardly expect me to know much about his youth.

If I was sure, however, that what I tell you would not go the

whole round of Prattigau, I

Comments (0)