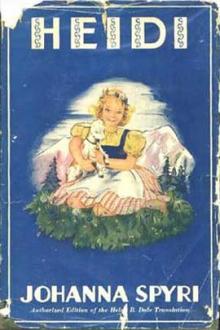

Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗

- Author: Johanna Spyri

- Performer: 0753454947

Book online «Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗». Author Johanna Spyri

branches waving outside.

Then it grew very cold, and Peter would come up early in the

morning blowing on his fingers to keep them warm. But he soon

left off coming, for one night there was a heavy fall of snow

and the next morning the whole mountain was covered with it, and

not a single little green leaf was to be seen anywhere upon it.

There was no Peter that day, and Heidi stood at the little window

looking out in wonderment, for the snow was beginning again, and

the thick flakes kept falling till the snow was up to the

window, and still they continued to fall, and the snow grew

higher, so that at last the window could not be opened, and she

and her grandfather were shut up fast within the hut. Heidi

thought this was great fun and ran from one window to the other

to see what would happen next, and whether the snow was going to

cover up the whole hut, so that they would have to light a lamp

although it was broad daylight. But things did not get as bad as

that, and the next day, the snow having ceased, the grandfather

went out and shovelled away the snow round the house, and threw

it into such great heaps that they looked like mountains standing

at intervals on either side the hut. And now the windows and door

could be opened, and it was well it was so, for as Heidi and her

grandfather were sitting one afternoon on their three-legged

stools before the fire there came a great thump at the door

followed by several others, and then the door opened. It was

Peter, who had made all that noise knocking the snow off his

shoes; he was still white all over with it, for he had had to

fight his way through deep snowdrifts, and large lumps of snow

that had frozen upon him still clung to his clothes. He had been

determined, however, not to be beaten and to climb up to the

hut, for it was a week now since he had seen Heidi.

“Good-evening,” he said as he came in; then he went and placed

himself as near the fire as he could without saying another

word, but his whole face was beaming with pleasure at finding

himself there. Heidi looked on in astonishment, for Peter was

beginning to thaw all over with the warmth, so that he had the

appearance of a trickling waterfall.

“Well, General, and how goes it with you?” said the grandfather,

“now that you have lost your army you will have to turn to your

pen and pencil.”

“Why must he turn to his pen and pencil?” asked Heidi

immediately, full of curiosity.

“During the winter he must go to school,” explained her

grandfather, “and learn how to read and write; it’s a bit hard,

although useful sometimes afterwards. Am I not right, General?”

“Yes, indeed,” assented Peter.

Heidi’s interest was now thoroughly awakened, and she had so

many questions to put to Peter about all that was to be done and

seen and heard at school, and the conversation took so long that

Peter had time to get thoroughly dry. Peter had always great

difficulty in putting his thoughts into words, and he found his

share of the talk doubly difficult to-day, for by the time he had

an answer ready to one of Heidi’s questions she had already put

two or three more to him, and generally such as required a whole

long sentence in reply.

The grandfather sat without speaking during this conversation,

only now and then a twitch of amusement at the corners of his

mouth showed that he was listening.

“Well, now, General, you have been under fire for some time and

must want some refreshment, come and join us,” he said at last,

and as he spoke he rose and went to fetch the supper out of the

cupboard, and Heidi pushed the stools to the table. There was

also now a bench fastened against the wall, for as he was no

longer alone the grandfather had put up seats of various kinds

here and there, long enough to hold two persons, for Heidi had a

way of always keeping close to her grandfather whether he was

walking, sitting or standing. So there was comfortable place for

them all three, and Peter opened his round eyes very wide when

he saw what a large piece of meat Alm-Uncle gave him on his thick

slice of bread. It was a long time since Peter had had anything

so nice to eat. As soon as the pleasant meal was over Peter

began to get ready for returning home, for it was already growing

dark. He had said his “good-night” and his thanks, and was just

going out, when he turned again and said, “I shall come again

next Sunday, this day week, and grandmother sent word that she

would like you to come and see her one day.”

It was quite a new idea to Heidi that she should go and pay

anybody a visit, and she could not get it out of her head; so

the first thing she said to her grandfather the next day was, “I

must go down to see the grandmother to-day; she will be expecting

me.”

“The snow is too deep,” answered the grandfather, trying to put

her off. But Heidi had made up her mind to go, since the

grandmother had sent her that message. She stuck to her

intention and not a day passed but what in the course of it she

said five or six times to her grandfather, “I must certainly go

to-day, the grandmother will be waiting for me.”

On the fourth day, when with every step one took the ground

crackled with frost and the whole vast field of snow was hard as

ice, Heidi was sitting on her high stool at dinner with the

bright sun shining in upon her through the window, and again

repeated her little speech, “I must certainly go down to see the

grandmother to-day, or else I shall keep her waiting too long.”

The grandfather rose from table, climbed up to the hayloft and

brought down the thick sack that was Heidi’s coverlid, and said,

“Come along then!” The child skipped out gleefully after him

into the glittering world of snow.

The old fir trees were standing now quite silent, their branches

covered with the white snow, and they looked so lovely as they

glittered and sparkled in the sunlight that Heidi jumped for joy

at the sight and kept on calling out, “Come here, come here,

grandfather! The fir trees are all silver and gold!” The

grandfather had gone into the shed and he now came out dragging

a large hand-sleigh along with him; inside it was a low seat, and

the sleigh could be pushed forward and guided by the feet of the

one who sat upon it with the help of a pole that was fastened to

the side. After he had been taken round the fir trees by Heidi

that he might see their beauty from all sides, he got into the

sleigh and lifted the child on to his lap; then he wrapped her

up in the sack, that she might keep nice and warm, and put his

left arm closely round her, for it was necessary to hold her

tight during the coming journey. He now grasped the pole with his

right hand and gave the sleigh a push forward with his two feet.

The sleigh shot down the mountain side with such rapidity that

Heidi thought they were flying through the air like a bird, and

shouted aloud with delight. Suddenly they came to a standstill,

and there they were at Peter’s hut. Her grandfather lifted her

out and unwrapped her. “There you are, now go in, and when it

begins to grow dark you must start on your way home again.” Then

he left her and went up the mountain, pulling his sleigh after

him.

Heidi opened the door of the hut and stepped into a tiny room

that looked very dark, with a fireplace and a few dishes on a

wooden shelf; this was the little kitchen. She opened another

door, and now found herself in another small room, for the place

was not a herdsman’s hut like her grandfather’s, with one large

room on the ground floor and a hayloft above, but a very old

cottage, where everything was narrow and poor and shabby. A

table was close to the door, and as Heidi stepped in she saw a

woman sitting at it, putting a patch on a waistcoat which Heidi

recognised at once as Peter’s. In the corner sat an old woman,

bent with age, spinning. Heidi was quite sure this was the

grandmother, so she went up to the spinning-wheel and said, “Good-day, grandmother, I have come at last; did you think I was a long

time coming?”

The woman raised her head and felt for the hand that the child

held out to her, and when she found it, she passed her own over

it thoughtfully for a few seconds, and then said, “Are you the

child who lives up with Alm-Uncle, are you Heidi?”

“Yes, yes,” answered Heidi, “I have just come down in the sleigh

with grandfather.”

“Is it possible! Why your hands are quite warm! Brigitta, did Alm-Uncle come himself with the child?”

Peter’s mother had left her work and risen from the table and

now stood looking at Heidi with curiosity, scanning her from head

to foot. “I do not know, mother, whether Uncle came himself; it

is hardly likely, the child probably makes a mistake.”

But Heidi looked steadily at the woman, not at all as if in any

uncertainty, and said, “I know quite well who wrapped me in my

bedcover and brought me down in the sleigh: it was grandfather.”

“There was some truth then perhaps in what Peter used to tell us

of Alm-Uncle during the summer, when we thought he must be

wrong,” said grandmother; “but who would ever have believed that

such a thing was possible? I did not think the child would live

three weeks up there. What is she like, Brigitta?”

The latter had so thoroughly examined Heidi on all sides that

she was well able to describe her to her mother.

“She has Adelaide’s slenderness of figure, but her eyes are dark

and her hair curly like her father’s and the old man’s up there:

she takes after both of them, I think.”

Heidi meanwhile had not been idle; she had made the round of the

room and looked carefully at everything there was to be seen.

All of a sudden she exclaimed, “Grandmother, one of your shutters

is flapping backwards and forwards; grandfather would put a nail

in and make it all right in a minute, or else it will break one

of the panes some day; look, look, how it keeps on banging!”

“Ah, dear child,” said the old woman, “I am not able to see it,

but I can hear that and many other things besides the shutter.

Everything about the place rattles and creaks when the wind is

blowing, and it gets inside through all the cracks and holes.

The house is going to pieces, and in the night, when the two

others are asleep, I often lie awake in fear and trembling,

thinking that the whole place will give way and fall and kill us.

And there is not a creature to mend anything for us, for Peter

does not understand such work.”

“But why cannot you see, grandmother, that the shutter is loose.

Look,

Comments (0)