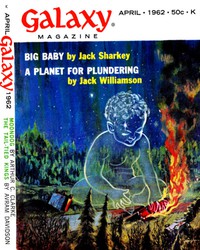

Big Baby by Jack Sharkey (most inspirational books of all time .TXT) 📗

- Author: Jack Sharkey

Book online «Big Baby by Jack Sharkey (most inspirational books of all time .TXT) 📗». Author Jack Sharkey

"Sir?"

"Tell Captain—" Jerry began, then realized his voice was nearly a ragged shout, and lowered it. "Would you please tell the captain to speed things up if he can, Ollie?"

Ollie hesitated. "The vector—" he started, then stiffened militarily and replied, "Yes, sir. At once, sir."

"No," Jerry groaned, closing his eyes and hanging onto the metal edge of the doorframe. "Forget it. He's got a course to follow in. He can't get there any faster."

Ollie, knowing this already, just stood there.

"Just go have a cup of coffee," Jerry added, lamely. "And about what I said—"

"You know I wouldn't say anything about it, sir," Ollie said.

"I know," Jerry admitted. "Sorry. Space nerves or something of the sort, I guess."

"Sure, sir."

The mess boy turned and continued down the passageway. Jerry shut the door slowly, then sat down in his chair once more, and stared at the clock, and sipped the hot coffee, and fought the cold needle-pricks of fear in every muscle and joint of his body....

II

The colony on the second planet of Sirius existed solely due to one of those vicious circles of progress. Just as iron is needed to make the steel to build the tools and equipment necessary to mine the raw iron ore, so this colony was needed to mine the precious mineral that made such colonies possible in the first place.

The mineral was called Praesodynimium, a polysyllabic mouthful which meant simply that it was an unstable crystalline isotope of sodium that broke down eventually into ordinary sodium (hence "prae-":before; "sod-":sodium), which was possessed of extreme kinetic potentials ("dyn-":power), and was first extracted from sodium compounds by a Canadian scientist ("-imium" instead of the more American "-inum" or even "-um").

This crystal had the happy habit of electrical allergy. When subjected to even a mild electric current, it avoided the consequent shakeup of its electronic juxtaposition by simply vanishing from normal space until the power was turned off. The nice part about its disappearance—from an astronaut's point of view—was that the crystal took not only itself, but objects within a certain radius along with it. It turned out that a crystal of Praesodynimium the moderate size of a sixteen-inch softball would warp a ninety-foot spaceship into hyperspace without even breathing hard. Of course, it would warp anything else within a fifty-foot radius, too; so it was only turned on after the ship had ascended beyond planetary atmosphere, lest a large scoop of landing-field, not to mention a few members of the ground crew, be carried away with the ship.

In her eagerness to investigate the now-attainable stars, Earth had soon exhausted her sources of the mineral. Worse, the crystal, being unstable, had a half-life of only twenty-five years. That meant that a ship using it had a full-range radial margin of about five years before the crystal ceased warping the ship-inclusive area.

Until some way was discovered to get into hyperspace without using Praesodynimium—and its actual function was as much a mystery to scientists as an automobile's cause-and-effect is to a lot of drivers; very few people can describe the esoteric relationships between the turning of the ignition key and the turning of the rear wheels—the mineral was worth ten times its weight in uranium 235.

Sirius II had been found to be as rife with the mineral as a candy store is with calories. Hence the colony.

For so long as the ore held out the planet would be regarded with fond respect and esteem by any and all persons who had investments, relatives or even just interest in the Space Age and its contingent programs.

So it was with considerable trepidation that Earth received the news that the mines on Sirius were no longer being worked. Oh, yes, there was still ore—enough to keep the planet profitable for another century. The trouble was the miners. They weren't coming out of the mines anymore. And no one who went inside to look for them was ever seen again, either.

Naturally, mining slacked off. The men refused to set foot in the mines until somebody found out what had happened to their predecessors.

So the officials of the colony resurrected a scanner-beam and roborocket from the cellar of the spacefield warehouse and storage depot. They sent the rocket into an orbit matching planetary rotation. In effect it simply hovered over the mines while it scanned the area for uncatalogued alien life.

And when they brought the rocket down and checked the microtape against the file of known species on the planet, they found that no such beast had ever been catalogued. Its life-pulse gave a reading of point-nine-nine-nine.

Since life-pulses are catalogued on a decimal scale based on the numeral one (with Man rated at point-oh-five-oh), the colonial administration staff immediately ordered the mines officially closed and off-limits. This brought no results on Sirius II which had not been already achieved, but the declaration made the miners feel a little less guilty over their dereliction of duty.

An SOS was swiftly sent to Earth, explaining the situation in detail and requesting instructions.

Earth sent word to hang on, keep calm and leave the mines closed until an investigation could be made—all of which the colony was trying to do anyway.

A duplicate of the microtape had been transmitted along with the SOS. Earth had checked the pattern against every known species filed in U.S. Naval Space Corps Alien-Contact Library, a collection of the vast alien multitude gathered by Space Zoologists in the methodical colonization and exploration of the universe. It was found to be not only unknown anywhere in the thus-far-explored cosmos, but totally unlike any life-pulse previously encountered.

Earth decided the only way to get any satisfaction would be by the unorthodox method of sending in a Space Zoologist to Contact the alien, though this would be the first time in the history of Contact that this had ever been done on an already-settled planet.

And so the badly frightened colony lingered behind bolted doors, and peered through locked windows at the sky—awaiting the arrival of Jerry Norcriss, and praying he'd locate the alien and tell them how it might be dealt with....

"Begging your pardon, sir," grinned the tech, doing some last-minute fiddling with the machine, "but you never had it so good." Jerry dabbed at the cold sweat-film on his forehead and upper lip, and nodded silently.

In all his previous Contacts, done before any colonization was even attempted, things were a bit more rustic. His present environs were luxury compared to those setups. If the six-month orbit of the roborocket found the planet safe for humans, well and good; Jerry did not have to go. But if a new life-form were spotted—one that did not correspond in life-pulse to any known species—then it was Jerry's job to land on the planet and Learn the beast, to determine its probable menace, if any, to man.

The tech was referring to the fact that Jerry's usual base of operations was out on the sward beside the tailfin of the rocket, the only power-source on a non-colonized planet. There, in his Contact helmet, relaxed upon his padded couch, he would let his mind be sent right into that of the alien, to Learn it from the inside out. Here, though, on a settled world, his accommodations were pleasantly out of the ordinary. He was in the solarium of the town's research laboratory-hospital. He gazed up through quartz panes at soothing blue skies, in air-conditioned comfort spoiled only by a fugitive scent of disinfectant lingering in the building.

Some half-dozen curious members of the building's staff were gathered in the room. None of them had ever seen a man go into Contact before. In vain the tech had assured them, before Jerry's arrival, that there was nothing to be seen. Jerry would lie on the couch and adjust the helmet upon his head, and then the tech would throw a switch. And for forty minutes there would be nothing to see except Jerry's silent supine body.

Later, of course, the information transmitted by Jerry's mind through the helmet pickups to the machine would be translated into English. Then they could all read about the new animal. That would be the interesting part, for them; not this senseless staring at the young man, white-haired at thirty-plus, who would, so far as they'd be able to tell, merely doze off for an uneventful forty-minute nap.

For Jerry, however, things would be anything but dull for those forty minutes.

Once the process was begun, there was no way known even to the discoverer of the Contact principle to extend or reduce the time-period. When Jerry's mind had traveled to that of the alien, he would remain there for the full time. Anything that happened to the alien in that period would also happen to Jerry. Including death.

If the alien somehow perished with Jerry "aboard," as it were, the group in the solarium would wait in vain for him ever to bestir himself and rise from the couch again.

Jerry, fighting the waves of nausea that burned in the pit of his stomach, lay there in his helmet and waited for the tech to finish adjusting the machine.

A scanner-beam, sent toward the suspected locale from the solarium, had instantly retriggered that same green blip in response, as jagged and powerful as before. Jerry would soon be sent right into the center of the response-area, and his mind imbedded in the brain of the alien.

"Hurry it up, will you?" Jerry called over to the tech, trying not to shout.

"Ready, sir," the other man said abruptly. "Are you all set?"

"All set, Ensign," Jerry replied, then shut his eyes to the clear blue sky and the stares of the curious and let his mind relax for the brief shock of transport....

A flare of lightning, silent, white and cold in his mind—and Jerry Norcriss was in Contact....

One of the nurses, crisp and efficient in white starched cotton, took a hesitant step toward the figure on the couch, then spoke to the tech without looking at him, intensely. "What are his chances? It's so important that he succeed!"

About to brush her off with a noncommittal reply, the tech turned his gaze from the control panel to meet, turning to face him, a pair of the deepest blue eyes he'd ever seen, and a smooth-skinned serious face beneath a short-cropped tangle of bright yellow hair. The eyes were troubled. His manner softened instantly.

Trying not to show the sudden warmth he felt, he pointed with offhand authority at the tall metal machine, its face alive with leaping lights and quivering indicator needles.

"This'll tell the story, one way or the other," he said. "A Space Zoologist's chances are always fifty-fifty. He either succeeds and returns in perfect health, or he fails and doesn't return at all. But whatever data he picks up in Contact will be punched onto the microtape. It may help us deal with the menace. Or it may not."

She looked surprised. "Then this is simply a recorder? I'd thought it was the thing that sent his mind out to the mine area...." She faltered on the last few words, and looked more concerned than ever.

The tech was tempted to ask her about it, but decided to stay on the neutral ground of simple mechanics for a while. "No, his mind sends itself. That is, the helmet triggers a certain brain-center; his mind follows a scanner-beam directed toward the alien and he Contacts. After that, this machine could be turned off, so far as maintaining Contact goes. After a forty-minute interim, his mind would return to his body by itself. The brain-center gets triggered sort of like a muscle reacts to a blow. It gets paralyzed for a certain time. Forty minutes. Beyond that limit, or short of it, no Contact or breaking of Contact is possible...."

His voice trailed off as he realized her responsive nods were abstracted and vague, her thoughts elsewhere. "Look," he said awkwardly, "I'm no psyche-man, but—maybe it'd help if you talked about it."

A faint smile touched her mouth. "I didn't realize it showed."

He grinned and shrugged.

"My name's Jana," she said. "Jana Corby." She was trying to ease some of the natural tension between strangers.

"Bob Ryder," said the tech. He stood and waited for her to make the next move.

"My father—" she said, and for the first time, some of the tension behind her eyes flowed over into her voice. "My father was one of the miners. He was on the morning shift. The day the men didn't come home was the day before my wedding."

Bob frowned. "I don't understand."

She blinked at the moisture that had come to her eyes, and flashed him a sad little smile. "I'm sorry. I was telescoping events. You see, with Dad missing, I postponed the ceremony, naturally, till I could learn what had happened. Jim—that's Jim Herrick, my fiance—was wonderfully understanding about it. He's a miner, too. On the night-shift, thank God. But if Lieutenant Norcriss doesn't succeed—if he can't find

Comments (0)