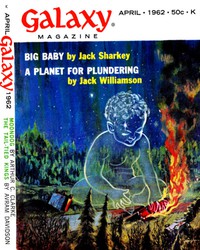

Big Baby by Jack Sharkey (most inspirational books of all time .TXT) 📗

- Author: Jack Sharkey

Book online «Big Baby by Jack Sharkey (most inspirational books of all time .TXT) 📗». Author Jack Sharkey

"How can you know my aloneness?" asked Jerry.

"I see it, there in your mind. It is plain to me. You have been misled. You are a helpless pawn of a singularly wicked scheme. The victim of a lie."

Jerry's recollection flashed to his conversation with Ollie Gibbs, to the things he had wanted to tell the other man but was unable to put into words. All the heaviness he had borne alone these many years was apparent to this mind he enhosted. The alien mind knew. Knew!

"I see," it said again, though Jerry was unaware of expressing any conscious thought. "It is clear to me now. You have suffered much—will suffer much. No hope for you, is there?"

There was warmth in the words—warmth, friendship and compassionate understanding. Suddenly, to this mind of an alien in its incongruous, invisible baby's body, Jerry found himself blurting the things he had never told to any man. Things which no Space Zoologist had ever discussed even with another member of that hapless clan.

"They never told us," he said to the alien. "I don't hold any rancor because of it; they dared not tell us, lest we refuse to become one with them. They were fair, though. Long before we were indoctrinated, long before we'd been allowed to attempt our first Contact, we were told that there were dangers. Not the dangers we had heard about, such as the imminent peril of dying if the host died while we were in Contact. Another danger was implied, one which we could only learn of by actually becoming Learners, and one which—once we had learned of it—would be impossible to escape.

"With a little thought along the proper lines, we might almost have guessed it. For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. One of Newton's laws, applied in an area he did not even suspect existed.

"Oh, we were a brave, adventurous lot, all of us. We would be Learners; no alien mind but we could enter it, and actually become the alien for the period of Contact. Thrills, danger and hairsbreadth escapes would be ours. Ultimate adventurers, they called us. And all along, we were fools."

The alien refrained from comment, although Jerry could feel its mind waiting, listening, assimilating.

"Contact had a drawback. A basic one which we might have guessed, if we hadn't been going around with stars in our eyes and a delightful feeling of superiority over the men who would never know the interior on any minds but their own. In Contact, just as in sunbathing, there is a delayed reaction, a kickback."

"Sunbathing?" thought the alien.

Jerry's mind swiftly opened for the alien's inspection his full storehouse of information on the subject. In an instant, the alien apprehended the fate that lay in wait for the careless Space Zoologist—

"Sure is warm in here," said Bob, running a finger around inside his sweat-dampened uniform collar.

"You have to be careful," said Jana, indicating the quartz panes that formed the ceiling and three walls of the solarium. "The quartz passes ultraviolet, unlike glass. You can pick up a severe burn if you sit out here too long without some sort of protection for your skin."

The tech nodded. "The insidious thing about sunburn is that you only turn a little pink as long as you're out in the sunlight. It's when you've gone indoors, or the sun has set, or you put your clothes back on that the red-hot burn begins to show up on your flesh."

"It's the light-pressure," said Jana. "As long as there's an influx of ultraviolet, the flesh continues to absorb it without showing much reaction. But as soon as you get away from the rays—the burns show up.... I wonder how Norcriss is making out."

IV

"You mean, then," said the alien to Jerry, "that all the experiences you undergo in Contact are held back under the surface of your mind, waiting there until you let up on the incoming Contact experiences?"

"That's it," said Jerry, miserably. "In some of my Contacts, I've undergone pretty painful experiences. I've had an eye twisted out, an arm eaten and digested, been poisoned, nearly strangled—you name a near-death; I've been through it."

"And your reaction?" thought the mind.

"Nil," said Jerry, ruefully. "When I awakened from a Contact, my memory of my experiences was strictly a mental one. Like something I'd read in a book. There was no emotional reaction whatsoever. My heart beat its normal amount, my glands excreted normal perspiration, my muscles were relaxed. Not a trace of shock or any other after effect."

"And later?" the mind asked gently.

"Back on Earth," said Jerry, "the Space Zoologists have a thing we call the Comprehension Chamber. It's a room filled with couches and helmets, in which we can listen—through replayed microtapes—to all the Contacts our confreres have ever made. Perhaps 'listen' is a weak word. For all practical purposes, we are in Contact, so long as the tape runs. I thought this room was a wonderful adjunct to my education, but nothing more. I went there a lot at first. It was even more fun than the real thing because there was no danger of perishing. Tapes of zoologists who died while in Contact are never used in the Chamber."

The mind waited, listening patiently.

"So one week—" Jerry's mind gave a mental twinge akin to a physical shudder—"one week I got bored. I decided not to go to the Comprehensive Chamber. I went out on a few dates, instead. Tennis, the movies, like that. And on the third day, I woke in the morning with a heart trying to pound its way through my ribs, with my bedsheets dripping with cold perspiration, and lancing agony in my eye, my hand knotted into a fist of pain, lungs burning for air...."

"Delayed reaction," said the mind.

"Yes," said Jerry. "That was it. I recognized the pains right away, having been through them personally in Contact only a month before them. I had a horrible inkling of what was occurring. I called the medics at Space Corps Headquarters before I passed out. They came, shot me full of morphine and stuck me into a helmet for twenty-four hours straight, to cram my reactive agonies back beneath an overload of vicarious Contacts. It worked pretty well. The pain was gone when I awakened. But my nerves weren't the same afterward. I used to look forward to Contacts because I enjoyed them. Now I look forward to them because I dread what will happen if I don't have another one in time."

"In time?"

"I find that I must get to a Contact—real or vicarious—at least once in forty-eight hours. I've been trapped by my job. I'm doomed to do this job or die horribly. Some men, desperate for escape from this treadmill, have quit the Corps, tried to battle this kickback-effect. None of them have made it. They were found, all of them, in various states of agony. Dead, broken, burnt, torn...."

"Psychosomatic pressures?" asked the mind.

"Yes. Their minds, overborne by their emotions, self-hypnotized them into re-undergoing their experiences. And their bodies, duped by their minds, reacted. On a normal man, a hypnotically suggested burn can raise an actual blister. On a man who's opened his mind to the Contact-power—his body can break, burn, dissolve or even evaporate."

"Poor Jerry," said the alien mind, soothingly. A tingle formed slowly in Jerry's mind, a growing warmth, a vibration of utter affection. He was being consoled, being loved by the alien. It knew his troubles. It understood the sorrow of his life. It wanted only to keep him close, to tell him not to be afraid, to make him happy, comfortable, safe.... Safe, and secure, and—

The glare of silent lightning leaped through Jerry's consciousness, jerking him back from the unnervingly delightful torpor he'd been letting overcome his thoughts.

Something hard bumped against his forehead. He realized that he'd just sat up on the couch, knocking the helmet from his head with the shock of the breaking Contact.

"Sir!" said the tech, pausing only to snap off the circuit switch before dashing to his side. "What the hell happened? I never saw you break Contact like that! Did you see the alien? Can it be destroyed?"

Jerry groaned, tried to speak, then fell back onto the thick padding, unconscious.

"What's the matter with him?" cried Jana, sensing the fright in the tech's attitude.

"I don't know," he whispered. "I've never seen him act this way before. Whatever's out there, it's unlike anything we've ever encountered before! Here, you get some of your medics up here to see to him. I'm going to process this damned tape and see what's what!"

Her face pale, Jana hurried off to do his bidding. The tech began to reset the machine so that the coded information on the tape might be translated into legible words.

And Jerry Norcriss lay on the couch, sobbing and groaning like a man on the rack, although his mind was blanked by merciful unconsciousness.

"A baby?" choked the tech. "That thing out there is a baby?"

"Does the tape ever lie?" sighed Jerry, relaxing against the plump white pillows Jana had arranged under his back and shoulders.

"Well, no," faltered the tech. "But a baby! Five hundred feet high—and invisible—and able to carry on an intelligent conversation?"

"Which reminds me," said Jerry, sternly. "I am going to ask you to edit both the tape and that typewritten translation of that conversation. It's just as well too many people don't get the inside story on my job, and its rather rugged drawback. And as for yourself.... Well, I can't order you to forget what you've read there."

"I won't talk about it, sir, if that's what you mean," said the tech. "It's not such a hard secret to keep. All the crewmen on the ship know there's something pretty awful about your job. I just happen to know what. All I'd get for spilling the inside dope would be, 'Oh, is that what it is!' Hardly worth it."

"That's hardly a noble reason to keep a secret," Jerry murmured, looking narrow-eyed at the tech.

The man grinned, then shrugged. "Makes my life easy, too. Now when you flare up at me, I'll know why, and skip it."

"Thanks a hell of a lot," Jerry muttered.

The tech laughed aloud.

"But," the zoologist added soberly, "we did learn one surprising lesson today. The forty-minute Contact period can be broken, under certain stresses."

The smile left the tech's face, and he looked earnestly puzzled. "I don't follow you, sir. There was nothing on the tape about—"

"Tape?" said Jerry. "You saw how quickly I came out, didn't you? What's that got to do with the tape?"

"Sir," the tech said hesitantly, "you were under the helmet for the full forty."

Jerry flopped back upon the pillows, staring at the other man as if he'd suddenly gone berserk. "That can't be," he said slowly. "I was in a long-life host. The clouds weren't even moving. That baby was living many subjective days in the forty-minute period."

"Begging your pardon, sir," said the tech, "but you must be mistaken. You were gone the full forty."

"That's impossible," said Jerry.

Jana, who'd been standing back from the two men, stepped forward cautiously, apprehensive at butting into something that was not really her affair.

"Excuse me, Lieutenant Norcriss," she said softly, "but Bob's right. You were gone as long as he says."

"You don't understand, either of you!" Jerry snapped. "My time-awareness in a host is subject to the host's time-awareness. So far as this host was concerned, a day was a confoundedly long period. But I could tell the elapsed time by watching the clouds, the height of the sun. They didn't move, either of them, visibly...."

"How's that again, sir?" asked the tech. "How long did you seem to spend?"

"Possibly an hour."

"Well, then." The tech shrugged.

"But this had nothing to do with the host's subjective sense of time, Ensign. It was my own knowledge of objective time through watching the sun, the trees, the clouds. None of them moved during my subjective hour in the host-alien. So no time—or very little time; barely a few minutes—could have passed while I was enhosted, do you see?"

"Lieutenant Norcriss," said Jana, abruptly. "I'm sorry to interrupt, but did you say clouds?"

"Yes," said Jerry, puzzled by her intensity. "Why?"

"There hasn't been a cloud in the sky today," she said awkwardly. "I mean—Well, look for yourself!"

Jerry turned his gaze upward through the quartz ceiling of the solarium. The sky, a rich turquoise, was smooth and unbroken save for the glaring gold orb of the sun, Sirius. He sat up then, looking out through the likewise transparent walls. As far as he could see, over storetops, cottage roofs, and distant green glades, the sky was that same unbroken blue.

"But that's crazy!" he said, sinking back against the pillows. "It couldn't have been like that all the

Comments (0)