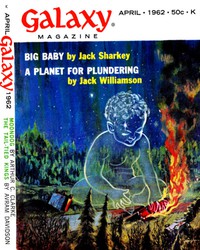

Big Baby by Jack Sharkey (most inspirational books of all time .TXT) 📗

- Author: Jack Sharkey

Book online «Big Baby by Jack Sharkey (most inspirational books of all time .TXT) 📗». Author Jack Sharkey

Jana nodded.

"The alien," Jerry said softly, "was a mimic. A perfect mimic. It was, while non-intelligent, of an abnormally well developed mind in one function: telepathy. That's how it could carry on apparently intelligent mental conversation with me, during my first contact. It could sense my questions, then probe my mind for the answers I wanted most to hear—and play them back to me. For my forty minutes of contact, it told me only what I wanted to know, like a selective echo. It needed no understanding of my questions, nor of the answers it plucked from my mind. It had one instinct: self-preservation. It could sense my question, select an uncontroversial answer from my mind and feed it back to me, without really understanding how it warded me off as a menace to it, any more than a dog understands why lowering its ears and hanging its head as it whines can fend off the wrath of its master. It works; that's all the creature cares about."

"But how did you know—?" Jana asked.

"I didn't," Jerry replied. "It fooled me completely. Until the Ensign—Bob told me that my full forty minutes in Contact had elapsed, despite my knowledge that the sun and clouds had remained motionless during my Contact. That threw me, I'll admit, for quite a while. It just didn't make sense."

Jana's eyes widened as she suddenly understood. "And then you realized that you had seen the sun and clouds motionless because that was what you expected to experience when enhosted in a baby!"

"That's it," Jerry nodded. "It made an error with the baby, though. It was able to duplicate it in almost every respect except two: Size and appearance."

"Why?" asked Jana. "And why appear as a baby at all?"

"I'm coming to that," said Jerry. "The size was off because the first thing I saw when I blinked open my eyes was a distant copse of trees, which I took to be an upright pile of leafy twigs. Since my mind possessed information regarding the relative size of babies and twigs, the alien immediately made sure my mind saw other things in the same perspective. By the time it realized it had made an error, it was too late to normalize the baby's dimensions; that would have given its fakery away."

"But why did the thing choose a baby?"

"Because that was the thing's protection! It had a powerful hypnotic power, one that worked on its victims' minds directly through its telepathic interference with sensory perception. It always appeared as the thing the victim would be least likely to harm. In my case, a baby. But it made a slight error there, too. I'm a bachelor, Jana. There's only one baby with whom I ever had any great amount of experience: myself."

"And the invisibility?"

"I have no recollection, even now, of my body when I was a baby. I may have stared at my toes, played with my fingers, but they just never registered on my consciousness as being part of myself. So the thing was stuck when it came to reproducing me visually, since it depended upon my own memory for details. But it was able to supply the way I'd felt as a baby. Every baby has an acute awareness of its own skin; it will cry if any particle of its flesh is bothered in the slightest. So the alien fed the 'feel' of my baby-body back to me, if not the view. Which is why the electronic brain on the ship was able to duplicate the detail into an almost perfect replica of my babyhood likeness."

Jana nodded, as she finally understood the meaning of that strange illusion. "And this time? That post-hypnotic suggestion you had the doctor give you, I mean: that you'd think you were a gray rat until such time as the light of the arc-torch caught you directly in the eyes...."

"Duplicity, Jana. It had to be that way. The alien was very sure of its powers. If I returned, and it were a baby again, I couldn't attack it or thwart its ends. And such an attack was necessary. I had to be able to fight it, to hold it in place for that last moment before it was destroyed. Which is why I chose a gray rat, an animal I cannot bear the sight of. When the light struck my eyes and I became myself again, I caught the alien unawares. Then, before it could change to a baby, and start lulling me back into camaraderie, it was too late. Bob had given the order to fire. And here I am."

Hurrying footsteps sounded in the corridor. The door burst open and Bob rushed in, his face anxious and creased with worry until he saw Jerry sitting on the couch, alive and well.

"Whoosh!" The tech expelled a mingled chuckle and sigh as he sank into a chair opposite the zoologist. "Well, sir, I can't tell you how glad I am to see you. I couldn't be sure you'd gotten out of that thing alive until I got back here. Glad you made it, sir. Damn glad!"

"That 'thing' you mentioned," said Jerry. "What did it actually look like?"

Bob jerked his head toward the corridor. "The other guys are bringing it along. I kind of thought you'd want a peep at it."

As more footfalls were heard from the corridor, Bob bounced to his feet again, and stepped to the door. "Hold it a minute, guys," he said, then turned back into the room. "Jana, I don't think you'd better stick around for this. It's not very pretty."

The girl hesitated, then flashed him a smile and shook her head. "I'll stay. It can't look as ugly as a bad case of peritonitis on the surgeon's table. If I can take that without upchucking, I can take anything."

Bob shrugged. "Suit yourself, honey. Just remember you got fair warning." He leaned back out the door. "Okay. Bring it in."

The crewmen, looking a little ill, came slowly into the room, bearing a bloated, scorched object on a stretcher they'd contrived from two long poles and their jackets. They set it onto the tiled floor before the zoologist, then stepped away, all of them wiping their hands hard against their trousers in ludicrous unison, though their grip on the poles had not brought them into actual contact with the alien's corpse.

"There it is, sir," said Ollie Gibbs. "And you are very welcome to it."

Jana, to her credit, had not upchucked, but she went a shade paler, and her mouth grew tight.

Jerry studied the burnt husk, from its sharp-fanged mouth—easily eighteen inches from side to side—to its stubby centipedal cilia under the grossly swollen body.

"Damn thing's all bloat, slime and mouth," said the tech, suddenly shuddering. "I wonder if its victims felt those jaws rending them open, or if it kept their minds fooled through to the end?"

"I don't think we'll ever know that, Ensign," said Jerry. "Unless you feel like going out there and playing victim to one of this thing's confreres?"

"No thanks, sir," said Bob, so swiftly that Jana laughed. "I'd rather fall out an airlock in hyperspace."

"Well, here's what we do to get rid of this thing, then," said Jerry. "Since it assumes a form that's the least likely to be harmed by whatever presence stimulates its mimetic senses, we'll have to trick it. Before this thing decomposes too far, rig it up with an electrical charge, and stimulate its nerve-centers artificially. That ought to give you an accurate microtape of its life-pulse. Then hook the tape to a scanner-beam, and send the life-pulse into the mine-area. When the fellows of this creature react to it, they'll assume the safest possible form: their own."

"I get you, sir!" said Bob. "Then all the miners have to do is see it for what it is, and shoot it."

Jerry nodded. "It'll mean all miners will have to go armed for awhile. But that's better than getting eaten alive by one of these."

"You sure their presence won't trigger the thing's mimetic power?" asked Bob, uneasily.

"Not if you give full power to the scanner-beam," Jerry replied. "It'll muffle their life-pulse radiations under the brunt of the artificial one."

"Good enough, sir," said Bob. "I'll rig it right away."

Jerry shook his head. "No need. You could use some rest, I'm sure. The morning'll be soon enough. Meantime, you can see this young lady home. The rest of you," he said to the hovering crewmen, "are dismissed, too."

The men, eager to be away from the thing, saluted smartly and hurried out of the solarium, buzzing with wordy relief.

Jana paused a moment, staring at the creature whose strange powers had destroyed her father. Then she turned to Bob.

"I think I'll go to Jim's place," she said. "I want him to know." She moved her gaze to Jerry. "I owe you a lot," she said. "We all owe you a lot."

Embarrassed by the warmth of her praise, Jerry could only mumble something diffident and look the other way. He was taken quite by surprise by the pressure of cool moist lips against the side of his face.

When he looked back at the pair, Bob and Jana were on their way out the door.

Only when he heard the elevator doors at the end of the corridor close behind them did he move to the still-warm corpse of his onetime adversary, with a look of deepest compassion on his face.

"Well," he said gently, "you've lost. The planet goes back to the invaders. Once again, Earth has successfully obliterated the opposition."

He reached out a hand and touched the hulking thing on the floor. "Good-by," he said. "And I'm sorry."

Jerry Norcriss wasn't thinking about the deadliness of the thing, nor of the deaths of the hapless miners, nor of the billions of dollars he'd saved the investors holding Praesodynimium stock. He was thinking of a voice that—even unintelligently, even in the course of deception—had said, "Poor Jerry. Rest.... Relax. You're safe.... Secure...."

"You really had me going for a while, baby," he said, then blinked at the sudden sharp sting in his eyes, and hurried from the room.

Outside, the sun was glowing pink against the black eastern sky, and the air was cool and fresh in his nostrils. As he crossed the street from the hospital, heading toward the landing field and his shipboard bunk, a hurrying figure from the end of the block caught up with him and began to pace his stride, panting slightly.

"Talk about happy," said Bob, glumly. "When Jana told her boy friend the news, they went into such a clinch I didn't even stick around to be introduced. Seemed a nice enough guy, I guess. Hope she'll be happy with him."

Jerry recognized the gloominess of the tech's mood, and its cause, so didn't say anything. After a moment, Bob seemed to recover himself a little.

"Sir," he said, "there's one thing still bugs me about this alien."

"Oh?" said Jerry, halting. "What's that, Ensign?"

"How'd the initial roborocket miss the thing and its kind when it circled the planet before colonization began?"

"That's a moot question," said Jerry. "But my conjecture is that the scanner always caught it when it was assuming some other form. Since its victims were always indigenous to this planet, the things familiar to them were also of this planet, and the scanner-beam couldn't detect any life-pulses which were dissimilar to already-known species."

"I'll be damned," said Bob. "It's almost childishly simple when you explain it." Then, as Jerry went to start off again, Bob stopped him with an exclamation.

"What about that melting mine car I read about on the translation sheets? Was that for real, or wasn't it?"

Jerry shook his head. "Part of the general mimetic illusion, like the motionless clouds and unmoving trees. It let me see what I expected to see. In reality, I was just in the woods near the mine area, where you came upon the creature to destroy it." Jerry started slowly moving away once more.

A few steps further, and Bob halted again. "One final point, sir. That life-pulsing reading of point-nine-nine-nine. If the thing's pulsation was that powerful, I should think it would've been a lot harder to knock off than it was."

"You're right," said Jerry. "It would have been. But its life-pulse wasn't nearly that high."

"But the scanner-beam—" Bob protested. "When the colony sent up that roborocket, after those miners vanished, it reported an unknown life-pulse of point-nine-nine-nine. If that wasn't the alien's life-pulse, what the devil was it?"

Jerry patted Bob on the shoulder. "You're forgetting the mimicry. The roborocket they sent up caught the alien off-guard, in its own shape, not imitating some other life-form's pulsations. It detected the beam, since a scanner picks up mental pulses, and it instantly

Comments (0)