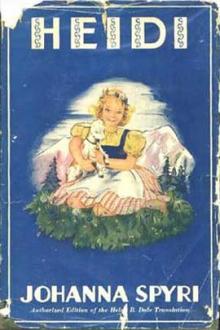

Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗

- Author: Johanna Spyri

- Performer: 0753454947

Book online «Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗». Author Johanna Spyri

thought, and that it was all hers again once more. And she was so

overflowing with joy and thankfulness that she could not find

words to thank Him enough. Not until the glory began to fade

could she tear herself away. Then she ran on so quickly that in

a very little while she caught sight of the tops of the fir trees

above the hut roof, then the roof itself, and at last the whole

hut, and there was grandfather sitting as in old days smoking

his pipe, and she could see the fir trees waving in the wind.

Quicker and quicker went her little feet, and before Alm-Uncle

had time to see who was coming, Heidi had rushed up to him,

thrown down her basket and flung her arms round his neck, unable

in the excitement of seeing him again to say more than

“Grandfather! grandfather! grandfather!” over and over again.

And the old man himself said nothing. For the first time for

many years his eyes were wet, and he had to pass his hand across

them. Then he unloosed Heidi’s arms, put her on his knee, and

after looking at her for a moment, “So you have come back to me,

Heidi,” he said, “how is that? You don’t look much of a grand

lady. Did they send you away?”

“Oh, no, grandfather,” said Heidi eagerly, “you must not think

that; they were all so kind—Clara, and grandmamma, and Herr

Sesemann. But you see, grandfather, I did not know how to bear

myself till I got home again to you. I used to think I should

die, for I felt as if I could not breathe; but I never said

anything because it would have been ungrateful. And then

suddenly one morning quite early Herr Sesemann said to me—but I

think it was partly the doctor’s doing—but perhaps it’s all in

the letter—” and Heidi jumped down and fetched the roll and the

letter and handed them both to her grandfather.

“That belongs to you,” said the latter, laying the roll down on

the bench beside him. Then he opened the letter, read it through

and without a word put it in his pocket.

“Do you think you can still drink milk with me, Heidi?” he

asked, taking the child by the hand to go into the hut. “But

bring your money with you; you can buy a bed and bedclothes and

dresses for a couple of years with it.”

“I am sure I do not want it,” replied Heidi. “I have got a bed

already, and Clara has put such a lot of clothes in my box that

I shall never want any more.”

“Take it and put it in the cupboard; you will want it some day I

have no doubt.”

Heidi obeyed and skipped happily after her grandfather into the

house; she ran into all the corners, delighted to see everything

again, and then went up the ladder—but there she came to a

pause and called down in a tone of surprise and distress, “Oh,

grandfather, my bed’s gone.”

“We can soon make it up again,” he answered her from below. “I

did not know that you were coming back; come along now and have

your milk.”

Heidi came down, sat herself on her high stool in the old place,

and then taking up her bowl drank her milk eagerly, as if she

had never come across anything so delicious, and as she put down

her bowl, she exclaimed, “Our milk tastes nicer than anything

else in the world, grandfather.”

A shrill whistle was heard outside. Heidi darted out like a

flash of lightning. There were the goats leaping and springing

among the rocks, with Peter in their midst. When he caught sight

of Heidi he stood still with astonishment and gazed speechlessly

at her. Heidi called out, “Good-evening, Peter,” and then ran in

among the goats. “Little Swan! Little Bear! do you know me

again?” And the animals evidently recognized her voice at once,

for they began rubbing their heads against her and bleating

loudly as if for joy, and as she called the other goats by name

one after the other, they all came scampering towards her helter-skelter and crowding round her. The impatient Greenfinch sprang

into the air and over two of her companions in order to get

nearer, and even the shy little Snowflake butted the Great Turk

out of her way in quite a determined manner, which left him

standing taken aback by her boldness, and lifting his beard in

the air as much as to say, You see who I am.

Heidi was out of her mind with delight at being among all her

old friends again; she flung her arms round the pretty little

Snowflake, stroked the obstreperous Greenfinch, while she

herself was thrust at from all sides by the affectionate and

confiding goats; and so at last she got near to where Peter was

still standing, not having yet got over his surprise.

“Come down, Peter,” cried Heidi, “and say good-evening to me.”

“So you are back again?” he found words to say at last, and now

ran down and took Heidi’s hand which she was holding out in

greeting, and immediately put the same question to her which he

had been in the habit of doing in the old days when they

returned home in the evening, “Will you come out with me again tomorrow?”

“Not tomorrow, but the day after perhaps, for tomorrow I must

go down to grandmother.”

“I am glad you are back,” said Peter, while his whole face

beamed with pleasure, and then he prepared to go on with his

goats; but he never had had so much trouble with them before, for

when at last, by coaxing and threats, he had got them all

together, and Heidi had gone off with an arm over either head of

her grandfather’s two, the whole flock suddenly turned and ran

after her. Heidi had to go inside the stall with her two and shut

the door, or Peter would never have got home that night. When

Heidi went indoors after this she found her bed already made up

for her; the hay had been piled high for it and smelt

deliciously, for it had only just been got in, and the

grandfather had carefully spread and tucked in the clean sheets.

It was with a happy heart that Heidi lay down in it that night,

and her sleep was sounder than it had been for a whole year past.

The grandfather got up at least ten times during the night and

mounted the ladder to see if Heidi was all right and showing no

signs of restlessness, and to feel that the hay he had stuffed

into the round window was keeping the moon from shining too

brightly upon her. But Heidi did not stir; she had no need now

to wander about, for the great burning longing of her heart was

satisfied; she had seen the high mountains and rocks alight in

the evening glow, she had heard the wind in the fir trees, she

was at home again on the mountain.

CHAPTER XIV. SUNDAY BELLS

Heidi was standing under the waving fir trees waiting for her

grandfather, who was going down with her to grandmother’s, and

then on to Dorfli to fetch her box. She was longing to know how

grandmother had enjoyed her white bread and impatient to see and

hear her again; but no time seemed weary to her now, for she

could not listen long enough to the familiar voice of the trees,

or drink in too much of the fragrance wafted to her from the

green pastures where the golden-headed flowers were glowing in

the sun, a very feast to her eyes. The grandfather came out,

gave a look round, and then called to her in a cheerful voice,

“Well, now we can be off.”

It was Saturday, a day when Alm-Uncle made everything clean and

tidy inside and outside the house; he had devoted his morning to

this work so as to be able to accompany Heidi in the afternoon,

and the whole place was now as spick and span as he liked to see

it. They parted at the grandmother’s cottage and Heidi ran in.

The grandmother had heard her steps approaching and greeted her

as she crossed the threshold, “Is it you, child? Have you come

again?”

Then she took hold of Heidi’s hand and held it fast in her own,

for she still seemed to fear that the child might be torn from

her again. And now she had to tell Heidi how much she had

enjoyed the white bread, and how much stronger she felt already

for having been able to eat it, and then Peter’s mother went on

and said she was sure that if her mother could eat like that for

a week she would get back some of her strength, but she was so

afraid of coming to the end of the rolls, that she had only

eaten one as yet. Heidi listened to all Brigitta said, and sat

thinking for a while. Then she suddenly thought of a way.

“I know, grandmother, what I will do,” she said eagerly, “I will

write to Clara, and she will send me as many rolls again, if not

twice as many as you have already, for I had ever such a large

heap in the wardrobe, and when they were all taken away she

promised to give me as many back, and she would do so I am

sure.”

“That is a good idea,” said Brigitta; “but then, they would get

hard and stale. The baker in Dorfli makes the white rolls, and

if we could get some of those he has over now and then—but I can

only just manage to pay for the black bread.”

A further bright thought came to Heidi, and with a look of joy,

“Oh, I have lots of money, grandmother,” she cried gleefully,

skipping about the room in her delight, “and I know now what I

will do with it. You must have a fresh white roll every day, and

two on Sunday, and Peter can bring them up from Dorfli.”

“No, no, child!” answered the grandmother, “I cannot let you do

that; the money was not given to you for that purpose; you must

give it to your grandfather, and he will tell you how you are to

spend it.”

But Heidi was not to be hindered in her kind intentions, and she

continued to jump about, saying over and over again in a tone of

exultation, “Now, grandmother can have a roll every day and will

grow quite strong again—and, Oh, grandmother,” she suddenly

exclaimed with an increase of jubilation in her voice, “if you

get strong everything will grow light again for you; perhaps

it’s only because you are weak that it is dark.” The grandmother

said nothing, she did not wish to spoil the child’s pleasure. As

she went jumping about Heidi suddenly caught sight of the

grandmother’s song book, and another happy idea struck her,

“Grandmother, I can also read now, would you like me to read you

one of your hymns from your old book?”

“Oh, yes,” said the grandmother, surprised and delighted; “but

can you really read, child, really?”

Heidi had climbed on to a chair and had already lifted down the

book, bringing a cloud of dust with it, for it had lain

untouched on the shelf for a long time. Heidi wiped it, sat

herself down on a stool beside the old woman, and asked her which

hymn she should read.

“What you like, child, what you like,” and

Comments (0)