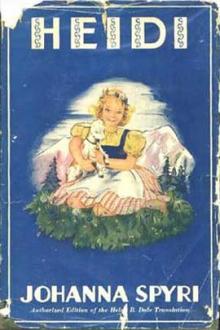

Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗

- Author: Johanna Spyri

- Performer: 0753454947

Book online «Heidi - Johanna Spyri (red scrolls of magic .txt) 📗». Author Johanna Spyri

her, if she would be reasonable and make no further fuss, that he

would take her to Switzerland next summer. So Clara gave in to

the inevitable, only stipulating that the box might be brought

into her room to be packed, so that she might add whatever she

liked, and her father was only too pleased to let her provide a

nice outfit for the child. Meanwhile Dete had arrived and was

waiting in the hall, wondering what extraordinary event had come

to pass for her to be sent for at such an unusual hour. Herr

Sesemann informed her of the state Heidi was in, and that he

wished her that very day to take her home. Dete was greatly

disappointed, for she had not expected such a piece of news. She

remembered Uncle’s last words, that he never wished to set eyes

on her again, and it seemed to her that to take back the child to

him, after having left it with him once and then taken it away

again, was not a safe or wise thing for her to do. So she excused

herself to Herr Sesemann with her usual flow of words; to-day and

tomorrow it would be quite impossible for her to take the

journey, and there was so much to do that she doubted if she

could get off on any of the following days. Herr Sesemann

understood that she was unwilling to go at all, and so dismissed

her. Then he sent for Sebastian and told him to make ready to

start: he was to travel with the child as far as Basle that day,

and the next day take her home. He would give him a letter to

carry to the grandfather, which would explain everything, and he

himself could come back by return.

“But there is one thing in particular which I wish you to look

after,” said Herr Sesemann in conclusion, “and be sure you

attend to what I say. I know the people of this hotel in Basle,

the name of which I give you on this card. They will see to

providing rooms for the child and you. When there, go at once

into the child’s room and see that the windows are all firmly

fastened so that they cannot be easily opened. After the child is

in bed, lock the door of her room on the outside, for the child

walks in her sleep and might run into danger in a strange house

if she went wandering downstairs and tried to open the front

door; so you understand?”

“Oh! then that was it?” exclaimed Sebastian, for now a light was

thrown on the ghostly visitations.

“Yes, that was it! and you are a coward, and you may tell John

he is the same, and the whole household a pack of idiots.” And

with this Herr Sesemann went off to his study to write a letter

to Alm-Uncle. Sebastian remained standing, feeling rather

foolish.

“If only I had not let that fool of a John drag me back into the

room, and had gone after the little white figure, which I should

do certainly if I saw it now!” he kept on saying to himself; but

just now every corner of the room was clearly visible in the

daylight.

Meanwhile Heidi was standing expectantly dressed in her Sunday

frock waiting to see what would happen next, for Tinette had

only woke her up with a shake and put on her clothes without a

word of explanation. The little uneducated child was far too much

beneath her for Tinette to speak to.

Herr Sesemann went back to the dining-room with the letter;

breakfast was now ready, and he asked, “Where is the child?”

Heidi was fetched, and as she walked up to him to say “Good-morning,” he looked inquiringly into her face and said, “Well,

what do you say to this, little one?”

Heidi looked at him in perplexity.

“Why, you don’t know anything about it, I see,” laughed Herr

Sesemann. “You are going home today, going at once.”

“Home,” murmured Heidi in a low voice, turning pale; she was so

overcome that for a moment or two she could hardly breathe.

“Don’t you want to hear more about it?”

“Oh, yes, yes!” exclaimed Heidi, her face now rosy with delight.

“All right, then,” said Herr Sesemann as he sat down and made

her a sign to do the same, “but now make a good breakfast, and

then off you go in the carriage.”

But Heidi could not swallow a morsel though she tried to do what

she was told; she was in such a state of excitement that she

hardly knew if she was awake or dreaming, or if she would again

open her eyes to find herself in her nightgown at the front

door.

“Tell Sebastian to take plenty of provisions with him,” Herr

Sesemann called out to Fraulein Rottenmeier, who just then came

into the room; “the child can’t eat anything now, which is quite

natural. Now run up to Clara and stay with her till the carriage

comes round,” he added kindly, turning to Heidi.

Heidi had been longing for this, and ran quickly upstairs. An

immense trunk was standing open in the middle of the room.

“Come along, Heidi,” cried Clara, as she entered; “see all the

things I have had put in for you—aren’t you pleased?”

And she ran over a list of things, dresses and aprons and

handkerchiefs, and all kinds of working materials. “And look

here,” she added, as she triumphantly held up a basket. Heidi

peeped in and jumped for joy, for inside it were twelve

beautiful round white rolls, all for grandmother. In their

delight the children forgot that the time had come for them to

separate, and when some one called out, “The carriage is here,”

there was no time for grieving.

Heidi ran to her room to fetch her darling book; she knew no one

could have packed that, as it lay under her pillow, for Heidi

had kept it by her night and day. This was put in the basket with

the rolls. Then she opened her wardrobe to look for another

treasure, which perhaps no one would have thought of packing—and

she was right—the old red shawl had been left behind, Fraulein

Rottenmeier not considering it worth putting in with the other

things. Heidi wrapped it round something else which she laid on

the top of the basket, so that the red package was quite

conspicuous. Then she put on her pretty hat and left the room.

The children could not spend much time over their farewells, for

Herr Sesemann was waiting to put Heidi in the carriage. Fraulein

Rottenmeier was waiting at the top of the stairs to say good-bye

to her. When she caught sight of the strange little red bundle,

she took it out of the basket and threw it on the ground. “No,

no, Adelaide,” she exclaimed, “you cannot leave the house with

that thing. What can you possibly want with it!” And then she

said good-bye to the child. Heidi did not dare take up her

little bundle, but she gave the master of the house an imploring

look, as if her greatest treasure had been taken from her.

“No, no,” said Herr Sesemann in a very decided voice, “the child

shall take home with her whatever she likes, kittens and

tortoises, if it pleases her; we need not put ourselves out

about that, Fraulein Rottenmeier.”

Heidi quickly picked up her bundle, with a look of joy and

gratitude. As she stood by the carriage door, Herr Sesemann gave

her his hand and said he hoped she would remember him and Clara.

He wished her a happy journey, and Heidi thanked him for all his

kindness, and added, “And please say good-bye to the doctor for

me and give him many, many thanks.” For she had not forgotten

that he had said to her the night before, ‘It will be all right

tomorrow,’ and she rightly divined that he had helped to make

it so for her. Heidi was now lifted into the carriage, and then

the basket and the provisions were put in, and finally Sebastian

took his place. Then Herr Sesemann called out once more, “A

pleasant journey to you,” and the carriage rolled away.

Heidi was soon sitting in the railway carriage, holding her

basket tightly on her lap; she would not let it out of her hands

for a moment, for it contained the delicious rolls for

grandmother; so she must keep it carefully, and even peep inside

it from time to time to enjoy the sight of them. For many hours

she sat as still as a mouse; only now was she beginning to

realize that she was going home to the grandfather, the

mountain, the grandmother, and Peter, and pictures of all she was

going to see again rose one by one before her eyes; she thought

of how everything would look at home, but this brought other

thoughts to her mind, and all of a sudden she said anxiously,

“Sebastian, are you sure that grandmother on the mountain is not

dead?”

“No, no,” said Sebastian, wishing to soothe her, “we will hope

not; she is sure to be alive still.”

Then Heidi fell back on her own thoughts again. Now and then she

looked inside the basket, for the thing she looked forward to

most was laying all the rolls out on grandmother’s table. After

a long silence she spoke again, “If only we could know for

certain that grandmother is alive!”

“Yes, yes,” said Sebastian, half asleep; “she is sure to be

alive, there is no reason why she should be dead.”

After a while sleep fell on Heidi too, and after her disturbed

night and early rising she slept so soundly that she did not

wake till Sebastian shook her by the arm and called to her, “Wake

up, wake up! we shall have to get out directly; we are just in

Basle!”

There was a further railway journey of many hours the next day.

Heidi again sat with her basket on her knee, for she would not

have given it up to Sebastian on any consideration; to-day she

never even opened her mouth, for her excitement, which increased

with every mile of the journey, kept her speechless. All of a

sudden, before Heidi expected it, a voice called out,

“Mayenfeld.” She and Sebastian both jumped up, the latter also

taken by surprise. In another minute they were both standing on

the platform with Heidi’s trunk, and the train was steaming away

down the valley. Sebastian looked after it regretfully, for he

preferred the easier mode of travelling to a wearisome climb on

foot, especially as there was danger no doubt as well as fatigue

in a country like this, where, according to Sebastian’s idea,

everything and everybody were half savage. He therefore looked

cautiously to either side to see who was a likely person to ask

the safest way to Dorfli.

Just outside the station he saw a shabby-looking little cart and

horse which a broad-shouldered man was loading with heavy sacks

that had been brought by the train, so he went up to him and

asked which was the safest way to get to Dorfli.

“All the roads about here are safe,” was the curt reply.

So Sebastian altered his question and asked which was the best

way to avoid falling over the precipice, and also how a box

could be conveyed to Dorfli. The man looked at the box, weighing

it with his eye, and then volunteered if it was not too heavy to

take it on his own cart, as he was driving to Dorfli. After

Comments (0)