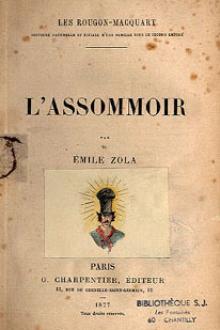

L'Assommoir - Émile Zola (best romantic books to read txt) 📗

- Author: Émile Zola

- Performer: -

Book online «L'Assommoir - Émile Zola (best romantic books to read txt) 📗». Author Émile Zola

The policeman allowed several minutes for the company to admire the bishop’s mitre and then finished cutting the slices and arranging them on the platter. The carving of the goose was now complete.

When the ladies complained that they were getting rather warm, Coupeau opened the door to the street and the gaiety continued against the background of cabs rattling down the street and pedestrians bustling along the pavement. The goose was attacked furiously by the rested jaws. Boche remarked that just having to wait and watch the goose being carved had been enough to make the veal and pork slide down to his ankles.

Then ensued a famous tuck-in; that is to say, not one of the party recollected ever having before run the risk of such a stomach-ache. Gervaise, looking enormous, her elbows on the table, ate great pieces of breast, without uttering a word, for fear of losing a mouthful, and merely felt slightly ashamed and annoyed at exhibiting herself thus, as gluttonous as a cat before Goujet. Goujet, however, was too busy stuffing himself to notice that she was all red with eating. Besides, in spite of her greediness, she remained so nice and good! She did not speak, but she troubled herself every minute to look after Pere Bru, and place some dainty bit on his plate. It was even touching to see this glutton take a piece of wing almost from her mouth to give it to the old fellow, who did not appear to be very particular, and who swallowed everything with bowed head, almost besotted from having gobbled so much after he had forgotten the taste of bread. The Lorilleuxs expended their rage on the roast goose; they ate enough to last them three days; they would have stowed away the dish, the table, the very shop, if they could have ruined Clump-Clump by doing so. All the ladies had wanted a piece of the breast, traditionally the ladies’ portion. Madame Lerat, Madame Boche, Madame Putois, were all picking bones; whilst mother Coupeau, who adored the neck, was tearing off the flesh with her two last teeth. Virginie liked the skin when it was nicely browned, and the other guests gallantly passed their skin to her; so much so, that Poisson looked at his wife severely, and bade her stop, because she had had enough as it was. Once already, she had been a fortnight in bed, with her stomach swollen out, through having eaten too much roast goose. But Coupeau got angry and helped Virginie to the upper part of a leg, saying that, by Jove’s thunder! if she did not pick it, she wasn’t a proper woman. Had roast goose ever done harm to anybody? On the contrary, it cured all complaints of the spleen. One could eat it without bread, like dessert. He could go on swallowing it all night without being the least bit inconvenienced; and, just to show off, he stuffed a whole drum-stick into his mouth. Meanwhile, Clemence had got to the end of the rump, and was sucking it with her lips, whilst she wriggled with laughter on her chair because Boche was whispering all sorts of smutty things to her. Ah, by Jove! Yes, there was a dinner! When one’s at it, one’s at it, you know; and if one only has the chance now and then, one would be precious stupid not to stuff oneself up to one’s ears. Really, one could see their sides puff out by degrees. They were cracking in their skins, the blessed gormandizers! With their mouths open, their chins besmeared with grease, they had such bloated red faces that one would have said they were bursting with prosperity.

As for the wine, well, that was flowing as freely around the table as water flows in the Seine. It was like a brook overflowing after a rainstorm when the soil is parched. Coupeau raised the bottle high when pouring to see the red jet foam in the glass. Whenever he emptied a bottle, he would turn it upside down and shake it. One more dead solder! In a corner of the laundry the pile of dead soldiers grew larger and larger, a veritable cemetery of bottles onto which other debris from the table was tossed.

Coupeau became indignant when Madame Putois asked for water. He took all the water pitchers from the table. Do respectable citizens ever drink water? Did she want to grow frogs in her stomach?

Many glasses were emptied at one gulp. You could hear the liquid gurgling its way down the throats like rainwater in a drainpipe after a storm. One might say it was raining wine. Mon Dieu! the juice of the grape was a remarkable invention. Surely the workingman couldn’t get along without his wine. Papa Noah must have planted his grapevine for the benefit of zinc-workers, tailors and blacksmiths. It brightened you up and refreshed you after a hard day’s work.

Coupeau was in a high mood. He proclaimed that all the ladies present were very cute, and jingled the three sous in his pocket as if they had been five-franc pieces.

Even Goujet, who was ordinarily very sober, had taken plenty of wine. Boche’s eyes were narrowing, those of Lorilleux were paling, and Poisson was developing expressions of stern severity on his soldierly face. All the men were as drunk as lords and the ladies had reached a certain point also, feeling so warm that they had to loosen their clothes. Only Clemence carried this a bit too far.

Suddenly Gervaise recollected the six sealed bottles of wine. She had forgotten to put them on the table with the goose; she fetched them, and all the glasses were filled. Then Poisson rose, and holding his glass in the air, said:

“I drink to the health of the missus.”

All of them stood up, making a great noise with their chairs as they moved. Holding out their arms, they clinked glasses in the midst of an immense uproar.

“Here’s to this day fifty years hence!” cried Virginie.

“No, no,” replied Gervaise, deeply moved and smiling; “I shall be too old. Ah! a day comes when one’s glad to go.”

Through the door, which was wide open, the neighborhood was looking on and taking part in the festivities. Passers-by stopped in the broad ray of light which shone over the pavement, and laughed heartily at seeing all these people stuffing away so jovially.

The aroma from the roasted goose brought joy to the whole street. The clerks on the sidewalk opposite thought they could almost taste the bird. Others came out frequently to stand in front of their shops, sniffing the air and licking their lips. The little jeweler was unable to work, dizzy from having counted so many bottles. He seemed to have lost his head among his merry little cuckoo clocks.

Yes, the neighbors were devoured with envy, as Coupeau said. But why should there be any secret made about the matter? The party, now fairly launched, was no longer ashamed of being seen at table; on the contrary, it felt flattered and excited at seeing the crowd gathered there, gaping with gluttony; it would have liked to have knocked out the shop-front and dragged the table into the roadway, and there to have enjoyed the dessert under the very nose of the public, and amidst the commotion of the thoroughfare. Nothing disgusting was to be seen in them, was there? Then there was no need to shut themselves in like selfish people. Coupeau, noticing the little clockmaker looked very thirsty, held up a bottle; and as the other nodded his head, he carried him the bottle and a glass. A fraternity was established in the street. They drank to anyone who passed. They called in any chaps who looked the right sort. The feast spread, extending from one to another, to the degree that the entire neighborhood of the Goutted’Or sniffed the grub, and held its stomach, amidst a rumpus worthy of the devil and all his demons. For some minutes, Madame Vigouroux, the charcoal-dealer, had been passing to and fro before the door.

“Hi! Madame Vigouroux! Madame Vigouroux!” yelled the party.

She entered with a broad grin on her face, which was washed for once, and so fat that the body of her dress was bursting. The men liked pinching her, because they might pinch her all over without ever encountering a bone. Boche made room for her beside him and reached slyly under the table to grab her knee. But she, being accustomed to that sort of thing, quietly tossed off a glass of wine, and related that all the neighbors were at their windows, and that some of the people of the house were beginning to get angry.

“Oh, that’s our business,” said Madame Boche. “We’re the concierges, aren’t we? Well, we’re answerable for good order. Let them come and complain to us, we’ll receive them in a way they don’t expect.”

In the back-room there had just been a furious fight between Nana and Augustine, on account of the Dutch oven, which both wanted to scrape out. For a quarter of an hour, the Dutch oven had rebounded over the tile floor with the noise of an old saucepan. Nana was now nursing little Victor, who had a goose-bone in his throat. She pushed her fingers under his chin, and made him swallow big lumps of sugar by way of a remedy. That did not prevent her keeping an eye on the big table. At every minute she came and asked for wine, bread, or meat, for Etienne and Pauline, she said.

“Here! Burst!” her mother would say to her. “Perhaps you’ll leave us in peace now!”

The children were scarcely able to swallow any longer, but they continued to eat all the same, banging their forks down on the table to the tune of a canticle, in order to excite themselves.

In the midst of the noise, however, a conversation was going on between Pere Bru and mother Coupeau. The old fellow, who was ghastly pale in spite of the wine and the food, was talking of his sons who had died in the Crimea. Ah! if the lads had only lived, he would have had bread to eat every day. But mother Coupeau, speaking thickly, leant towards him and said:

“Ah! one has many worries with children! For instance, I appear to be happy here, don’t I? Well! I cry more often than you think. No, don’t wish you still had your children.”

Pere Bru shook his head.

“I can’t get work anywhere,” murmured he. “I’m too old. When I enter a workshop the young fellows joke, and ask me if I polished Henri IV.‘s boots. To-day it’s all over; they won’t have me anywhere. Last year I could still earn thirty sous a day painting a bridge. I had to lie on my back with the river flowing under me. I’ve had a bad cough ever since then. Now, I’m finished.”

He looked at his poor stiff hands and added:

“It’s easy to understand, I’m no longer good for anything. They’re right; were I in their place I should do the same. You see, the misfortune is that I’m not dead. Yes, it’s my fault. One should lie down and croak when one’s no longer able to work.”

“Really,” said Lorilleux, who was listening, “I don’t understand why the Government doesn’t come to the aid of the invalids of labor. I was reading that in a newspaper the other day.”

But Poisson thought it his duty to defend the Government.

“Workmen are not soldiers,” declared he. “The Invalides is for soldiers. You must not ask for what is impossible.”

Dessert was now served.

Comments (0)