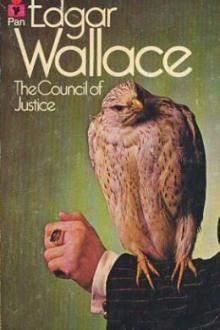

The Council of Justice - Edgar Wallace (best autobiographies to read TXT) 📗

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Book online «The Council of Justice - Edgar Wallace (best autobiographies to read TXT) 📗». Author Edgar Wallace

to enter the box. If I succeed—it will be finished. The knife is

best,’ there was pride in the Italian’s tone.

‘If I cannot reach him the honour will be yours.’ He had the stilted

manner of the young Latin. The other man grunted. He replied in halting

French.

‘Once I shot an egg from between fingers—so,’ he said.

They made their entry separately.

In the manager’s office, Superintendent Falmouth relieved the tedium

of waiting by reading the advertisements in an evening newspaper.

To him came the manager with a message that under no circumstances

was his Highness in Box A to be disturbed until the conclusion of the

performance.

In the meantime Signor Selleni made a cautious way to Box A. He

found the road clear, turned the handle softly, and stepped quickly

into the dark interior of the box.

Twenty minutes later Falmouth stood at the back of the dress circle

issuing instructions to a subordinate.

‘Have a couple of men at the stage door—my God!’

Over the soft music, above the hum of voices, a shot rang out and a

woman screamed. From the box opposite the Prince’s a thin swirl of

smoke floated.

Karl Ollmanns, tired of waiting, had fired at the motionless figure

sitting in the shadow of the curtain. Then he walked calmly out of the

box into the arms of two breathless detectives.

‘A doctor!’ shouted Falmouth as he ran. The door of the Box A was

locked, but he broke it open.

A man lay on the floor of the box very still and strangely

stiff.

‘Why, what—!’ began the detective, for the dead man was bound hand

and foot.

There was already a crowed at the door of the box, and he heard an

authoritative voice demand admittance.

He looked over his shoulder to meet the eye of the commissioner.

‘They’ve killed him, sir,’ he said bitterly.

‘Whom?’ asked the commissioner in perplexity.

‘His Highness.’

‘His Highness!’ the commissioner’s eyebrows rose in genuine

astonishment. ‘Why, the Prince left Charing Cross for the Continent

half an hour ago!’

The detective gasped.

‘Then who in the name of Fate is this?’

It was M. Menshikoff, who had come in with the commissioner, who

answered.

‘Antonio Selleni, an anarchist of Milan,’ he reported.

Carlos Ferdinand Bourbon, Prince of the Escorial, Duke of

Buda-Gratz, and heir to three thrones, was married, and his many august

cousins scattered throughout Europe had a sense of heartfelt

relief.

A prince with admittedly advanced views, an idealist, with Utopian

schemes for the regeneration of mankind, and, coming down to the

mundane practical side of life, a reckless motor-car driver, an

outrageously daring horseman, and possessed of the indifference to

public opinion which is equally the equipment of your fool and your

truly great man, his marriage had been looked forward to throughout the

courts of Europe in the light of an international achievement.

Said his Imperial Majesty of Central Europe to the grizzled

chancellor:

‘Te Deums—you understand, von Hedlitz? In every church.’

‘It is a great relief,’ said the chancellor, wagging his head

thoughtfully.

‘Relief!’ the Emperor stretched himself as though the relief were

physical, ‘that young man owes me two years of life. You heard of the

London essay?’

The chancellor had heard—indeed, he had heard three or four

times—but he was a polite chancellor and listened attentively. His

Majesty had the true story-telling faculty, and elaborated the

introduction.

‘…if I am to believe his Highness, he was sitting quietly in his

box when the Italian entered. He saw the knife in his hand and half

rose to grapple with the intruder. Suddenly, from nowhere in

particular, sprang three men, who had the assassin on the floor bound

and gagged. You would have thought our Carlos Ferdinand would have made

an outcry! But not he! He sat stock still, dividing his attention

between the stage and the prostrate man and the leader of this

mysterious band of rescuers.’

‘The Four Just Men!’ put in the chancellor.

‘Three, so far as I can gather,’ corrected the imperial

story-teller. ‘Well, it would appear that this leader, in quite a

logical calm, matter-of-fact way, suggested that the prince should

leave quietly; that his motor-car was at the stage door, that a saloon

had been reserved at Charing Cross, a cabin at Dover, and a special

train at Calais.’

His Majesty had a trick of rubbing his knee when anything amused

him, and this he did now.

‘Carl obeyed like a child—which seems the remarkably strange point

about the whole proceedings—the captured anarchist was trussed and

bound and sat on the chair, and left to his own unpleasant

thoughts.’

‘And killed,’ said the chancellor.

‘No, not killed,’ corrected the Emperor. ‘Part of the story I tell

you is his—he told it to the police at the hospital—no, no, not

killed—his friend was not the marksman he thought.’

CHAPTER IX. The Four v. The Hundred

Some workmen, returning home of an evening and taking a short cut

through a field two miles from Catford, saw a man hanging from a

tree.

They ran across and found a fashionably dressed gentleman of foreign

appearance. One of the labourers cut the rope with his knife, but the

man was dead when they cut him down. Beneath the tree was a black bag,

to which somebody had affixed a label bearing the warning, ‘Do not

touch—this bag contains explosives: inform the police.’ More

remarkable still was the luggage label tied to the lapel of the dead

man’s coat. It ran: ‘This is Franz Kitsinger, convicted at Prague in

1904, for throwing a bomb: escaped from prison March 17, 1905, was one

of the three men responsible for the attempt on the Tower Bridge today.

Executed by order of The Council of Justice.’

‘It’s a humiliating confession,’ said the chief commissioner when

they brought the news to him, ‘but the presence of these men takes a

load off my mind.’

But the Red Hundred were grimly persistent.

That night a man, smoking a cigar, strolled aimlessly past the

policeman on point duty at the corner of Kensington Park Gardens, and

walked casually into Ladbroke Square. He strolled on, turned a corner

and, crossing a road, he came to where one great garden served for a

double row of middle-class houses. The backs of these houses opened on

to the square. He looked round and, seeing the coast clear, he

clambered over the iron railings and dropped into the big pleasure

ground, holding very carefully an object that bulged in his pocket.

He took a leisurely view of the houses before he decided on the

victim. The blinds of this particular house were up and the French

windows of the dining-room were open, and he could see the laughing

group of young people about the table. There was a birthday party or

something of the sort in progress, for there was a great parade of

Parthian caps and paper sunbonnets.

The man was evidently satisfied with the possibilities for tragedy,

and he took a pace nearer…

Two strong arms were about him, arms with muscles like cords of

steel.

‘Not that way, my friend,’ whispered a voice in his ear…

The man showed his teeth in a dreadful grin.

The sergeant on duty at Notting Hill Gate Station received a note at

the hands of a grimy urchin, who for days afterwards maintained a

position of enviable notoriety.

‘A gentleman told me to bring this,’ he said.

The sergeant looked at the small boy sternly and asked him if he

ever washed his face. Then he read the letter:

‘The second man of the three concerned in the attempt to blow up the

Tower Bridge will be found in the garden of Maidham Crescent, under the

laurel bushes, opposite No. 72.’

It was signed ‘The Council of Justice’.

The commissioner was sitting over his coffee at the Ritz, when they

brought him the news. Falmouth was a deferential guest, and the chief

passed him the note without comment.

‘This is going to settle the Red Hundred,’ said Falmouth. ‘These

people are fighting them with their own weapons—assassination with

assassination, terror with terror. Where do we come in?’

‘We come in at the end,’ said the commissioner, choosing his words

with great niceness, ‘to clean up the mess, and take any scraps of

credit that are going’—he paused and shook his head. ‘I hope—I should

be sorry—’ he began.

‘So should I,’ said the detective sincerely, for he knew that his

chief was concerned for the ultimate safety of the men whose arrest it

was his duty to effect. The commissioner’s brows were wrinkled

thoughtfully.

‘Two,’ he said musingly; ‘now, how on earth do the Four Just Men

know the number in this—and how did they track them down—and who is

the third?—heavens! one could go on asking questions the whole of the

night!’

On one point the Commissioner might have been informed earlier in

the evening—he was not told until three o’clock the next morning. The

third man was Von Dunop. Ignorant of the fate of his fellow-Terrorists,

he sallied forth to complete the day notably.

The crowd at a theatre door started a train of thought, but he

rejected that outlet to ambition. It was too public, and the chance of

escape was nil. These British audiences did not lose their heads so

quickly; they refused to be confounded by noise and smoke, and a

writhing figure here and there. Von Dunop was no exponent of the Glory

of Death school. He greatly desired glory, but the smaller the risk,

the greater the glory. This was his code.

He stood for a moment outside the Hotel Ritz. A party of diners were

leaving, and motor-cars were being steered up to carry these accursed

plutocrats to the theatre. One soldierly-looking gentleman, with a grey

moustache, and attended by a quiet, observant, cleanshaven man,

interested the anarchist. He and the soldier exchanged glances.

‘Who the dickens was that?’ asked the commissioner as he stepped

into the taxi. ‘I seem to know his face.’

‘I have seen him before,’ said Falmouth. ‘I won’t go with you, sir—

I’ve a little business to do in this part of the world.’

Thereafter Von Dunop was not permitted to enjoy his walk in

solitude, for, unknown to him, a man ‘picked him up’ and followed him

throughout the evening. And as the hour grew later, that one man became

two, at eleven o’clock he became three, and at quarter to twelve, when

Von Dunop had finally fixed upon the scene and scope of his exploit, he

turned from Park Lane into Brook Street to discover, to his annoyance,

quite a number of people within call. Yet he suspected nothing. He did

not suspect the night wanderer mooching along the curb with downcast

eyes, seeking the gutter for the stray cigar end; nor the two loudly

talking men in suits of violet check who wrangled as they walked

concerning the relative merits of the favourites for the Derby; nor the

commissionaire trudging home with his bag in his hand and a pipe in his

mouth, nor the cleanshaven man in evening dress.

The Home Secretary had a house in Berkeley Square. Von Dunop knew

the number very well. He slackened pace to allow the man in evening

dress to pass. The slow-moving taxi that was fifty yards away he must

risk. This taxi had been his constant attendant during the last hour,

but he did not know

Comments (0)