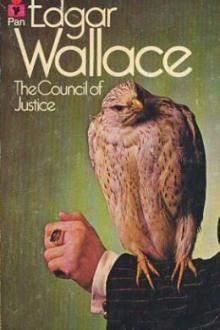

The Council of Justice - Edgar Wallace (best autobiographies to read TXT) 📗

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Book online «The Council of Justice - Edgar Wallace (best autobiographies to read TXT) 📗». Author Edgar Wallace

‘Also in England,’ he said.

‘What is your name?’ she asked. By an oversight it was a question

—she had not put before.

The man shrugged his shoulders.

‘Does it matter?’ he asked. A thought struck her. In the hall she

had seen Magnus the Jew. He had lived for many years in England, and

she beckoned him.

‘Of what class is this man?’ she asked in a whisper.

‘Of the lower orders,’ he replied; ‘it is astounding—did you not

notice when—no, you did not see his capture. But he spoke like a man

of the streets, dropping his aspirates.’

He saw she looked puzzled and explained.

‘It is a trick of the order—just as the Moujik says…’ he treated

her to a specimen of colloquial Russian.

‘What is your name?’ she asked again.

He looked at her slyly.

‘In Russia they called me Father Kopab…’

The majority of those who were present were Russian, and at the word

they sprang to their feet, shrinking back with ashen faces, as though

they feared contact with the man who stood bound and helpless in the

middle of the room.

The Woman of Gratz had risen with the rest. Her lips quivered and

her wide open eyes spoke her momentary terror.

‘I killed Starque,’ he went on, ‘by authority. Francois also. Some

day’—he looked leisurely about the room—‘I shall also—’

‘Stop!’ she cried, and then:

‘Release him,’ she said, and, wonderingly, Schmidt cut the bonds

that bound him. He stretched himself.

‘When you took me,’ he said, ‘I had a book; you will understand that

here in England I find—forgetfulness in books—and I, who have seen so

much suffering and want caused through departure from the law, am

striving as hard for the regeneration of mankind as you—but

differently.’

Somebody handed him a book.

He looked at it, nodded, and slipped it into his pocket.

‘Farewell,’ he said as he turned to the open door.

‘In God’s name!’ said the Woman of Gratz, trembling, ‘go in peace,

Little Father.’

And the man Jessen, sometime headsman to the Supreme Council, and

latterly public executioner of England, walked out, no man barring his

exit.

The power of the Red Hundred was broken. This much Falmouth knew. He

kept an ever-vigilant band of men on duty at the great termini of

London, and to these were attached the members of a dozen secret police

forces of Europe. Day by day, there was the same report to make. Such

and such a man, whose very presence in London had been unsuspected, had

left via Harwich. So-and-so, surprisingly sprung from nowhere, had gone

by the eleven o’clock train from Victoria; by the Hull and Stockholm

route twenty had gone in one day, and there were others who made

Liverpool, Glasgow, and Newcastle their port of embarkation.

I think that it was only then that Scotland Yard realized the

strength of the force that had lain inert in the metropolis, or

appreciated the possibilities for destruction that had been to hand in

the days of the Terror.

Certainly every batch of names that appeared on the commissioner’s

desk made him more thoughtful than ever.

‘Arrest them!’ he said in horror when the suggestion was made.

‘Arrest them! Look here, have you ever seen driver ants attack a house

in Africa? Marching in, in endless battalions at midnight and clearing

out everything living from chickens to beetles? Have you ever seen them

re-form in the morning and go marching home again? You wouldn’t think

of arresting ‘em, would you? No, you’d just sit down quietly out of

their reach and be happy when the last little red leg has disappeared

round the corner!’

Those who knew the Red Hundred best were heartily in accord with his

philosophy.

‘They caught Jessen,’ reported Falmouth. ‘Oh!’ said the

commissioner.

‘When he disclosed his identity, they got rid of him quick.’

‘I’ve often wondered why the Four Just Men didn’t do the business of

Starque themselves,’ mused the Commissioner.

‘It was rather rum,’ admitted Falmouth, ‘but Starque was a man under

sentence, as also was Francois. By some means they got hold of the

original warrants, and it was on these that Jessen—did what he

did.’

The commissioner nodded. ‘And now,’ he asked, ‘what about them?’

Falmouth had expected this question sooner or later. ‘Do you suggest

that we should catch them, sir?’-he asked with thinly veiled sarcasm;

‘because if you do, sir, I have only to remind you that we’ve been

trying to do that for some years.’ The chief commissioner frowned.

‘It’s a remarkable thing,’ he said, ‘that as soon as we get a

situation such as—the Red Hundred scare and the Four Just Men scare,

for instance, we’re completely at sea, and that’s what the papers will

say. It doesn’t sound creditable, but it’s so.’

‘I place the superintendent’s defence of Scotland Yard on record

in extenso.’

‘What the papers say,’ said Falmouth, ‘never keeps me awake at

night. Nobody’s quite got the hang of the police force in this

country—certainly the writing people haven’t.

‘There are two ways of writing about the police, sir. One way is to deal

with them in the newspaper fashion with the headline “Another Police

Blunder” or “The Police and The Public”, and the other way is to deal

with them in the magazine style, which is to show them as softies on the

wrong scent, whilst an ornamental civilian is showing them their

business, or as mysterious people with false beards who pop up at the

psychological moment, and say in a loud voice, “In the name of the Law,

I arrest you!”’

‘Well, I don’t mind admitting that I know neither kind. I’ve been a

police officer for twenty-three years, and the only assistance I’ve had

from a civilian was from a man named Blackie, who helped me to find the

body of a woman that had disappeared. I was rather prejudiced against

him, but I don’t mind admitting that he was pretty smart and followed

his clues with remarkable ingenuity.

‘The day we found the body I said to him:

‘“Mr. Blackie, you have given me a great deal of information

about this woman’s movements—in fact, you know a great deal more than

you ought to know—so I shall take you into custody on the suspicion of

having caused her death.”

‘Before he died he made a full confession, and ever since then I

have always been pleased to take as much advice and help from outside

as I could get.

‘When people sometimes ask me about the cleverness of Scotland Yard,

I can’t tell ‘em tales such as you read about. I’ve had murderers,

anarchists, burglars, and average low-down people to deal with, but

they have mostly done their work in a commonplace way and bolted. And

as soon as they have bolted, we’ve employed fairly commonplace methods

and brought ‘em back.

‘If you ask me whether I’ve been in dreadful danger, when arresting

desperate murderers and criminals, I say “No”.

‘When your average criminal finds himself cornered, he says,

“All right, Mr. Falmouth; it’s a cop”, and goes quietly.

‘Crime and criminals run in grooves. They’re hardy annuals with

perennial methods. Extraordinary circumstances baffle the police as

they baffle other folks. You can’t run a business on business lines and

be absolutely prepared for anything that turns up. Whiteley’s will

supply you with a flea or an elephant, but if a woman asked a shopgirl

to hold her baby whilst she went into the tinned meat department, the

girl and the manager and the whole system would be floored, because

there is no provision for holding babies. And if a Manchester goods

merchant, unrolling his stuff, came upon a snake lying all snug in the

bale, he’d be floored too, because natural history isn’t part of their

business training, and they wouldn’t be quite sure whether it was a big

worm or a boa constrictor.’

The Commissioner was amused.

‘You’ve an altogether unexpected sense of humour,’ he said, ‘and the

moral is—’

‘That the unexpected always floors you, whether it’s humour or

crime,’ said Falmouth, and went away fairly pleased with himself.

In his room he found a waiting messenger.

‘A lady to see you, sir.’

‘Who is it?’ he asked in surprise.

The messenger handed him a slip of paper and when he read it he

whistled.

‘The unexpected, by—! Show her up.’

On the paper was written—‘The Woman of Gratz…’

CHAPTER XI. Manfred

Manfred sat alone in his Lewisham house,—he was known to the old

lady who was his caretaker as ‘a foreign gentleman in the music

line’—and in the subdued light of the shaded lamp, he looked tired. A

book lay on the table near at hand, and a silver coffee-service and an

empty coffee-cup stood on the stool by his side. Reaction he felt. This

strange man had set himself to a task that was never ending. The

destruction of the forces of the Red Hundred was the end of a fight

that cleared the ground for the commencement of another—but physically

he was weary.

Gonsalez had left that morning for Paris, Poiccart went by the

afternoon train, and he was to join them tomorrow.

The strain of the fight had told on them, all three. Financially,

the cost of the war had been heavy, but that strain they could stand

better than any other, for had they not the fortune of—Courtlander; in

case of need they knew their man.

All the world had been searched before they—the first Four—had

come together—Manfred, Gonsalez, Poiccart, and the man who slept

eternally in the flower-grown grave at Bordeaux. As men taking the

oaths of priesthood they lived down the passions and frets of life.

Each man was an open book to the other, speaking his most secret

thought in the faith of sympathy, one dominating thought controlling

them all.

They had made the name of the Four Just Men famous or infamous

(according to your point of reckoning) throughout the civilized world.

They came as a new force into public and private life. There were men,

free of the law, who worked misery on their fellows; dreadful human

ghouls fattening on the bodies and souls of the innocent and helpless;

great magnates calling the law to their aid, or pushing it aside as

circumstances demanded. All these became amenable to a new law, a new

tribunal. There had grown into being systems which defied correction;

corporations beyond chastisement; individuals protected by cunningly

drawn legislation, and others who knew to an inch the scope of

toleration. In the name of justice, these men struck swiftly,

dispassionately, mercilessly. The great swindler, the procureur,

the suborner of witnesses, the briber of juries—they died.

There was no gradation of punishment: a warning, a second

warning—then death.

Thus their name became a symbol, at which the evildoer went

tremblingly about his work, dreading the warning and ready in most

cases to heed it. Life became a sweeter, a more wholesome thing for

many men who found the thin greenish-grey envelope on their

breakfast-table in the morning; but others persisted on their way,

loudly invoking the law, which in spirit, if not in letter, they had

outraged. The end was very sure, and I do not know of one man who

escaped the consequence.

Speculating on their identity, the police of the world decided

unanimously upon two points. The first was that these men were

enormously rich—as indeed they were, and the second that one or two of

them were no mean scientists—that also was true. Of the

Comments (0)