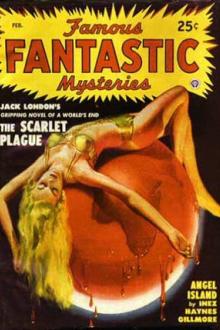

Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗

- Author: Inez Haynes Gillmore

- Performer: -

Book online «Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗». Author Inez Haynes Gillmore

“I tell you what we’ll do now,” Ralph suggested. “Put the first five

scarfs on the beach where they can get them. But if they want any more,

make them take them from our hands. Be careful, though, not to frighten

them. One move in their direction and we’ll undo everything we’ve

accomplished.”

As Ralph prophesied, the girls came again that day, but they waited

until after sunset. It was full-moon night, however; the island was as

white as day. They must have seen the gay-colored heaps from a distance;

they pounced on them at once. The air resounded with cooings of delight.

There was no doubt of it; the scarfs pleased them almost as much as the

mirrors. Before the first flush of their delight had passed, Honey ran

down the beach, bearing aloft a long, shimmering, white streamer. Ralph

followed with a scarf of black and gold. Billy, Pete, and Frank joined

them, each fluttering a brilliant silk gonfalon.

The girls drew away in alarm at first. Then they drew together for

counsel. All the time the men stood quiet, waving their delicately hued

spoils. One by one - Clara first, then Chiquita, Lulu, Peachy, Julia -

they succumbed; they sank slowly. Even then they floated for a long

while, visibly swinging between the desire for possession and the

instinct of caution. But in the end each one of them took from her mate

the scarf he held up to her. Followed the prettiest exhibition of flying

that Angel Island had yet seen. The girls fastened the long gauzes to

their heads and shoulders. They flicked and flitted and flittered, they

danced and pirouetted and spun through the air, trailing what in the

aqueous moonlight looked like mist, irradiated, star-sown.

“Well,” said Ralph that night after the girls had vanished, “I don’t see

that this business of handing out loot is getting us anywhere. We can

keep this up until we’ve given those harpies every blessed thing in the

trunks. Then where are we? They’ll have everything we have to give, and

we’ll be no nearer acquainted. We’ve got to do something else.”

“If we could only get them down to earth - if we could only accustom

them to walking about,” Honey declared, “I’m sure we could rig up some

kind of trap.”

“But you can’t get them to do that,” Billy said.

And the answer’s obvious. They can’t walk. You see how tiny, and

useless-looking their feet are. They’re no good to them, because they’ve

never used them. It never occurs to them apparently even to try to

walk.”

“Well, who would walk if he could fly?” demanded Pete pugnaciously.

“Well said, son,” agreed Ralph, “but what are we going to do about it?”

“I’ll tell you what we can do about it,” said Frank quietly, “if you’ll

listen to me.” The others turned to him. Their faces expressed varying

emotions - surprise, doubt, incredulity, a great deal of amusement. But

they waited courteously.

“The trouble has been heretofore,” Frank went on in his best academic

manner, “that you’ve gone at this problem in too obvious a way. You’ve

appealed to only one motive - acquisitiveness. There’s a stronger one

than that - curiosity.”

The look of politely veiled amusement on the four faces began to give

way to credulity. “But how, Frank?” asked Billy.

“I’ll show you how,” said Frank. “I’ve been thinking it out by myself

for over a week now.”

There was an air of quiet certainty about Frank. His companions looked

furtively at each other. The credulity in their faces changed to

interest. “Go on, Frank,” Billy said. They listened closely to his

disquisition.

“What ever gave you the idea, Frank?” Billy asked at the end.

“The fact that I found a Yale spring-lock the other day,” Frank answered

quietly.

The next morning, the men arose at sunrise and went at once to work.

They worked together on the big cabin - the Clubhouse - and they dug and

hammered without intermission all day long. Halfway through the morning,

the girls came flying in a group to the beach. The men paid no attention

to them. Many times their visitors flew up and down the length of the

crescent of white, sparkling sand, each time dropping lower, obviously

examining it for loot. Finding none, they flew in a body over the roof

of the Clubhouse, each face turned disdainfully away. The men took no

notice even of this. The girls gathered together in a quiet group and

obviously discussed the situation. After a little parley, they flew off.

Later in the afternoon came Lulu alone. She hovered at Honey’s shoulder,

displaying all her little tricks of graceful flying; but Honey was

obdurate. Apparently he did not see her. Came Chiquita, floating lazily

back and forth over Frank’s head like a monstrous, deeply colored

tropical bloom borne toward him on a breeze. She swam down close,

floated softly, but Frank did not even look in her direction. Came

Peachy with such marvels of flying, such diving and soaring, such

gyrating and flashing, that it took superhuman self-control not to drop

everything and stare. But nobody looked or paused. Came Clara, posturing

almost at their elbows. Came all save Julia, but the men ignored them

equally.

“Gee,” said Honey, after they had all disappeared, “that took the last

drop of resolution in me. By Jove, you don’t suppose they’ll get sore

and stay away for good?”

Frank shook his head.

Day by day the men worked on the Clubhouse; they worked their hardest

from the moment of sunrise to the instant of sunset. It was a square

building, big compared with the little cabins. They made a wide, heavy

door at one end and long windows with shutters on both sides. These were

kept closed.

“Only one more day’s work,” Frank said at the end of a fortnight, “and

then - .”

They finished the Clubhouse, as he prophesied, the next day.

“Now to furnish it,” Frank said.

They put up rough shelves and dressing-tables. They put in chairs and

hammocks. Then, working secretly at night when the moon was full, or in

the morning just after sunrise - at any time during the day when the

girls were not in sight - they transferred the contents of a half a

dozen women’s trunks to the Clubhouse. They hung the clothes

conspicuously in sight; they piled many small toilet articles on tables

and shelves; they placed dozens of mirrors about.

“It looks like a sale at the Waldorf,” Honey said as they stood

surveying the effect. “Tomorrow, we begin our psychological siege. Is

that right, Frank?”

“Psychological siege is right,” answered Frank with an unaccustomed

gayety and an unaccustomed touch of slang.

In the meantime the girls had shown their pique at this treatment in a

variety of small ways. Peachy and Clara made long detours around the

island in the effort not to pass near the camp. Chiquita and Lulu flew

overhead, but only in order to throw pebbles and sand down on the men

while they were working.

Julia alone took no part in this feud. If she was visible at all, it was

only as a glittering speck in the far-off reaches of the blue sky.

The next time the four girls approached the island, the men arose

immediately from their work. With an ostentatious carelessness, they

went into the Clubhouse. With an ostentatious carefulness, they closed

the door. They stayed there for three hours.

Outside, the girls watched this maneuver in visible astonishment. They

drew together and talked it over, flew down close to the Clubhouse, flew

about it in circles, examined it on every side, made even one perilous

trip across the roof, the tips of their feet tapping it in vicious

little dabs. But flutter as they would, jabber as they would, the

Clubhouse preserved a tomb-like silence. After a while they banged on

the shutters and knocked against the door; but not a sound or movement

manifested itself inside.

They flew away finally.

The next day the same thing happened - and the next - and the next.

But on the fourth day, something quite different occurred.

The instant the men saw the girls approaching, they carefully closed the

door and windows of the Clubhouse, and then marched into the interior of

the island. Close by the lake, there was a thick jungle of trees - a

place where the branches matted together, in a roof-like structure,

leaving a cleared space below. The men crawled into this shelter on

their hands and knees for an eighth of a mile. They stayed there three

hours.

The girls had followed this procession in an air-course that exactly

paralleled the trail. When the men disappeared under the trees, they

came together in a chattering group, obviously astonished, obviously

irritated. Hours went by. Not a thing stirred in the jungle; not a sound

came from it. The girls hovered and floated, dipped, dove, flew along

the edge of the lake close to the water, tried by looking under the

trees, to get what was going on. It was useless. Then they alighted on

the tree-tops and swung themselves down from branch to branch until they

were as near earth as they dared to come. Again they peered and peeped.

And again it was useless. In the end, flying and floating with the

disconsolate air of those who kill time, they frankly waited until the

men emerged from the jungle. Then, again the girls took up the airy

course that paralleled the trail to the camp.

For two weeks the men rigidly followed a program. Alternately they shut

themselves inside the Clubhouse and concealed themselves in the forest.

They stayed the same length of time in both places - never less than

three hours.

For two weeks, the girls rigidly followed a program. When the men

retired to the Clubhouse, they spent the three hours hovering over it,

sometimes banging viciously with feet and hands against the walls,

sometimes dropping stones on the roof. When the men retired to the

jungle, they spent the three hours beating about the branches of the

trees, dipping lower and lower into the underbrush, taking, as time went

on, greater and greater risks. But, as in both cases, the men were

screened from observation, all their efforts were useless.

Finally came a day with a difference. The men retired to the forest as

usual but, by an apparent inadvertence, they left the door of the

Clubhouse open a crack.

As usual the girls followed the men to the lake, but this time there was

a different air about them; they seemed to bubble with excitement. The

men crawled under the underbrush and waited. The girls made a

perfunctory search of the jungle and then, as at a concerted signal,

they darted like bolts of lightning back in the direction of the camp.

“I think we’ve got them, boys,” said Frank. There was a kind of

Berserker excitement about him, a wild note of triumph in his voice and

a white flare of triumph in his face. His breath came in excited gusts

and his nostrils dilated under the strain.

“I’m sure of it,” agreed Ralph. “And, by Jove, I’m glad. I’ve never had

anything so get on my nerves as this chase.” Ralph did, indeed, look

worn. Haggard and wild-eyed, he was shaking under the strain.

“Lord, I’m glad - but, Lord, it’s some responsibility,” said Honey

Smith. Honey was not white or drawn. He did not shake. But he had

changed. Still radiantly youthful, there was a new look in his face -

resolution.

“I feel like a mucker,” groaned Billy. He

Comments (0)