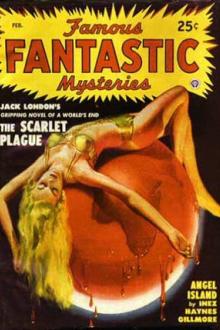

Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗

- Author: Inez Haynes Gillmore

- Performer: -

Book online «Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗». Author Inez Haynes Gillmore

Honey-Bunch crept across the mat of pine-needles, chasing an elusive

sunbeam. “No, she’s not there.”

“Now that I think of it, Angela didn’t come to play with Peterkin this

morning,” said Clara. “Generally she comes flying over just after

breakfast.”

“You don’t suppose Peachy’s ill,” asked Chiquita, “or Angela.”

“Oh, no!” Lulu answered. “Ralph would have told one of us.”

“Here she comes up the trail now,” Chiquita exclaimed. “Angela’s with

her.”

“Yes - but what’s the matter?” Lulu cried.

“She’s all bent over and she’s staggering.”

“She’s crying,” said Clara, after a long, intent look.

“Yes,” said Lulu. “She’s crying hard. And look at Angela - the darling!

She’s trying to comfort her.”

Peachy was coming slowly towards them; slowly because, although both

hands were on the rail, she staggered and stumbled. At intervals, she

dropped and crawled on hands and knees. At intervals, convulsions of

sobbing shook her, but it was voiceless sobbing. And those silent

cataclysms, taken with her blind groping progress, had a sinister

quality. Lulu and Julia tottered to meet her. “What is it, oh, what is

it, Peachy?” they cried.

Peachy did not reply immediately. She fought to control herself. “Go

down to the beach, baby,” she said firmly to Angela. “Stay there until

mother calls you. Fly away!”

The little girl fluttered irresolutely. “Fly away, dear!” Peachy

repeated. Angela mounted a breeze and made off, whirling, circling,

dipping, and soaring, in the direction of the water. Once or twice, she

paused, dropped and, bounding from earth to air, turned her frightened

eyes back to her mother’s face. But each time, Peachy waved her on.

Angela joined Honey-Boy and Peterkin. For a moment she poised in the

air; then she sank and began languidly to dig in the sand.

“I couldn’t let her hear it,” Peachy said. “It’s about her. Ralph - .”

She lost control of herself for a moment; and now her sobs had voice. “I

asked him last night about Angela and her flying. I don’t exactly know

why I did. It was something you said to me yesterday, Julia, that put it

into my head. He said that when she was eighteen, he was going to cut

her wings just as he cut mine.”

There came clamor from her listeners. “Cut Angela’s wings!” “Why?” “What

for?”

Peachy shook her head. “I don’t know yet why, although he tried all

night, to make me understand. He said that he was going to cut them for

the same reason that he cut mine. He said that it was all right for her

to fly now when she was a baby and later when she was a very young girl,

that it was ‘girlish’ and ‘beautiful’ and ‘lovely’ and ‘charming’ and

‘fascinating’ and - and - a lot of things. He said that he could not

possibly let her fly when she became a woman, that then it would be

‘unwomanly’ and ‘unlovely’ and ‘uncharming’ and ‘unfascinating.’ He said

that even if he were weak enough to allow it, her husband never would. I

could not understand his argument. I could not. It was as if we were

talking two languages. Besides, I could scarcely talk, I cried so. I’ve

cried for hours and hours and hours.”

“Sit down, Peachy,” Julia advised gently. “Let us all sit down.” The

women sank to their couches. But they did not lounge; they continued to

sit rigidly upright. “What are you going to do, Peachy?”

“I don’t know. But I’ll throw myself into the ocean with Angela in my

arms before I’ll consent to have her wings cut. Why, the things he said.

Lulu, he said that Angela might marry Honey-Boy, as they were the

nearest of age. He said that Honey-Boy would certainly cut her wings,

that he, no more than Honey, could endure a wife who flew. He said that

all earth-men were like that. Lulu, would you let your child do - do -

that to my child?”

Lulu’s face had changed - almost horribly. Her eyes glittered between

narrowed lids. Her lips had pulled away from each other, baring her

teeth. “You tell Ralph he’s mistaken about my son,” she ground out.

“That’s what I told him,” Peachy went on in a breaking voice. “But he

said you wouldn’t have anything to do or say about it. He said that

Honey-Boy would be trained in these matters by his father, not by his

mother. I said that you would fight them both. He asked me what chance

you would have against your husband and your son. He - he - he always

spoke as if Honey-Boy were more Honey’s child than yours, and as though

Angela were more his child than mine. He said that he had talked this

question over with the other men when Angela’s wings first began to

grow. He said that they made up their minds then that her wings must be

cut when she became a woman. I besought him not to do it - I begged, I

entreated, I pleaded. He said that nothing I could say would change him.

I said that you would all stand by me in this, and he asked me what we

five could do against them. He, called us five tottering females. Oh, it

grew dreadful. I shrieked at him, finally. As he left, he said,

‘Remember your first day in the Clubhouse, my dear! That’s my answer.’”

She turned to Clara. “Clara, you are going to bear a child in the

spring. It may be a girl. Would you let son of mine or any of these

women clip her wings? Will you suffer Peterkin to clip Angela’s wings?”

Clara’s whole aspect had fired. Flame seemed burst from her gray-green

eyes, sparks to shoot to from her tawny head. “I would strike him dead

first.”

Peachy turned to Chiquita. The color had poured into Chiquita’s face

until her full brown eyes glared from a purple mask. “You, too,

Chiquita. You may bear girl-children. Oh, will you help me?”

“I’ll help you,” Chiquita said steadily. She added after a pause, “I

cannot believe that they’ll dare, though.”

“Oh, they’ll dare anything,” Peachy said bitterly. Earth-men are devils.

What shall we do, Julia? she asked wearily.

Julia had arisen. She stood upright. Curiously, she did not totter. And

despite her shorn pinions, she seemed more than ever to tower like some

Winged Victory of the air. Her face ace glowed with rage. As on that

fateful day at the Clubhouse, it was as though a fire had been built in

an alabaster vase. But as they looked at her, a rush of tears wiped the

flame from her eyes. She sank back again on the couch. She put her hands

over her face and sobbed. “At last,” she said strangely. “At last! At

last! At last!”

“What shall we do, Julia?” Peachy asked stonily.

“Rebel!” answered Julia.

“But how?”

“Refuse to let them cut Angela’s wings.”

“Oh, I would not dare open the subject with Ralph,” Peachy said in a

terror-stricken voice. “In the mood he’s in, he’d cut her wings

tonight.”

“I don’t mean to tell him anything about it,” Julia replied. “Rebel in

secret. I mean - they overcame us once by strategy. We must beat them

now by superior strategy.”

“You don’t really mean anything secret, do you, Julia?” Lulu

remonstrated. “That wouldn’t be quite fair, would it?”

And curiously enough, Julia answered in the exact words that Honey had

used once. “Anything’s fair in love or war - and this is both. We can’t

be fair. We can’t trust them. We trusted them once. Once is enough for

me.”

“But how, Julia?” Peachy asked. Her voice had now a note of

querulousness in it. “How are we going to rebel?”

Julia started to speak. Then she paused. “There’s something I must ask

you first. Tell me, all of you, what did you do with your wings when the

men cut them off?”

The rage faded out of the four faces. A strange reticence seemed to blot

out expression. The reticence changed to reminiscence, to a deep

sadness.

Lulu spoke first. “I thought I was going to keep my wings as long as I

lived. I always thought of them as something wonderful, left over from a

happier time. I put them away, done up in silk. And at first I used to

look at them every day. But I was always sad afterwards - and - and

gradually, I stopped doing it. Honey hates to come home and find me sad.

Months went by - I only looked at them occasionally. And after a while,

I did not look at them at all. Then, one day, after Honey built the

fireplace for me, I saw that we needed something - to - to - to sweep

the hearth with. I tried all kinds of things, but nothing was right.

Then, suddenly, I remembered my wings. It had been two years since I’d

looked at them. And after that long time, I found that I didn’t care so

much. And so - and so - one day I got them out and cut them into little

brooms for the hearth. Honey never said anything about it - but I knew

he knew. Somehow - .” A strange expression came into the face of the

unanalytic Lulu. “I always have a feeling that Honey enjoys using my

wings about the hearth.”

Julia hesitated. “What did you do, Chiquita?”

“Oh, I had all Lulu’s feeling at first, of course. But it died as hers

did. You see this fan. You have often commented on how well I’ve kept it

all these years - I’ve mended it from month to month with feathers from

my own wings. The color is becoming to me - and Frank likes me to carry

a fan. He says that it makes him think of a country called Spain that he

always wanted to visit when he was a youth.”

“And you, Clara?” Julia asked gently.

“Oh, I went through,” Clara replied, “just what Lulu and Chiquita did.

Then, one day, I said to myself, ‘What’s the use of weeping over a, dead

thing?’ I made my wings into wall-decorations. You’re right about Honey,

Lulu.” For a moment there was a shade of conscious coquetry in Clara’s

voice. “I know that it gives Pete a feeling of satisfaction - I don’t

exactly know why (unless it’s a sense of having conquered) - to see my

wings tacked up on his bedroom walls.”

Peachy did not wait for Julia to put the question to her. “As soon as I

could move, after they freed us from the Clubhouse, I threw mine into

the sea. I knew I should go mad if I kept them where I could see them

every day. Just to look at them was like a sharp knife going through my

heart. One night, while Ralph was asleep, I crawled out of the house on

my hands and knees, dragging them after me. I crept down to the beach

and threw them into the water. They did not sink - they floated. I

stayed until they drifted out of sight. The moon was up. It shone on

them. Oh, the glorious blue of them - and the glitter - the - the - .”

But Peachy could not go on.

“What did you do with yours, Julia?” Lulu asked at last.

“I kept them until last night,” Julia answered.

Among the ship’s stuff was a beautiful carved chest. It was packed with

linen. Billy said it was some earth-girl’s wedding outfit. I took

Comments (0)