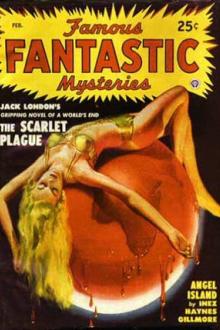

Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗

- Author: Inez Haynes Gillmore

- Performer: -

Book online «Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗». Author Inez Haynes Gillmore

into the interior for a week at a time.”

“But he would be just like all the others, Julia,” Clara exclaimed

carefully, “if you’d married him. Keep out of it as long as you can!”

“Don’t ever marry him, Julia,” Chiquita warned. “Keep your life a

perpetual wooing.”

“Marry him to-morrow, Julia,” Lulu advised. “Oh, I cannot think what my

life would have been without Honey-Boy and Honey-Bunch.”

“I shall marry Billy sometime,” Julia said. “But I don’t know when. When

that little inner voice stops saying, ‘Wait!’”

“I wonder,” Peachy questioned again, “what would have happened if - “

“It would have come out just the same way. Depend on that!” Chiquita

said philosophically. “It was our fate - the Great Doom that our people

used to talk of. And, after all, it’s our own fault. Come to this island

we would and come we did! And this is the end of it - we - we sit

moveless from sun-up to sun-down, we who have soared into the clouds.

But there is a humorous element in it. And if I didn’t weep, I could

laugh myself mad over it. We sit here helpless and watch these creatures

who walk desert us daily - desert us - creatures who flew - leave us

here helpless and alone.”

“But in the beginning,” Lulu interposed anxiously, “they did try to take

us with them. But it tired them so to carry us - for or that’s - what in

effect they do.”

“And there was one time just after we were married when it was all

wonderful,” said Peachy. “I did not even miss the flying, for it seemed

to me that Ralph made up for the loss of my wings by his love and

service. Then, they began to build the New Camp and gradually everything

changed. You see, they love their work more than they do us. Or at least

it seems to interest them more.”

“Why not?” Julia interpolated quietly. “We’re the same all the time. We

don’t change and grow. Their work does change and grow. It presents new

aspects every day, new questions and problems and difficulties, new

answers and solutions and adjustments. It makes them think all the time.

They love to think.” She added this as one who announces a discovery,

long pondered over. “They enjoy thinking.”

“Yes,” Lulu agreed wonderingly, “that’s true, isn’t it? That never

occurred to me. They really do like thinking. How curious! I hate to

think.”

“I never think,” Chiquita announced.

“I won’t think,” Peachy exclaimed passionately. “I feel. That’s the way

to live.”

“I don’t have to think,” Clara declared proudly. “I’ve something better

than thought-instinct and intuition.”

Julia was silent.

“Julia is like them,” Lulu said, studying Julia’s absent face tenderly.

“She likes to think. It doesn’t hurt, or bother, or irritate, or tire -

or make her look old. It’s as easy for her as breathing. That’s why the

men like to talk to her.”

“Well,” Clara remarked triumphantly, “I don’t have to think in order to

have the men about me. I’m very glad of that.”

This was true. The second year of their stay in Angel Island, the other

four women had rebuked Clara for this tendency to keep men about her -

without thinking.

“It is not necessary for us to think,” said Peachy with a sudden,

spirited lift of her head from her shoulders. The movement brought back

some of her old-time vivacity and luster. Her thick, brilliant, springy

hair seemed to rise a little from her forehead. And under her draperies

that which remained of what had once been wings stirred faintly. “They

must think just as they must walk because they are earth-creatures. They

cannot exist without infinite care and labor. We don’t have to think any

more than we have to walk; for we are air-creatures. And air-creatures

only fly and feel. We are superior to them.”

“Peachy,” Julia said again. Her voice thrilled as though some thought,

long held quiescent within her, had burst its way to expression. It rang

like a bugle. It vibrated like a violin-string. “That is the mistake

we’ve made all our lives; a mistake that has held us here tied to this

camp for or four our years;the idea that we are superior in some way,

more strong, more beautiful, more good than they. But think a moment!

Are we? True, we are as you say, creatures of the air. True, we were

born with wings. But didn’t we have to come down to the earth to eat and

sleep, to love, to marry, and to bear our young? Our trouble is that - “

And just then, “Here they come!” Lulu cried happily.

Lulu’s eyes turned away from the group of women. Her brown face had

lighted as though somebody had placed a torch beside it. The strings of

little dimples that her plumpness had brought in its wake played about

her mouth.

The trail that emerged from the jungle ran between bushes, and gradually

grew lower and lower, until it merged with a path shooting straight

across the sand to the Playground.

For a while the heads of the file of men appeared above the bushes; then

came shoulders, waists, knees; finally the entire figures. They strode

through the jungle with the walk of conquerors.

They were so absorbed in talk as not to realize that the camp was in

sight. Every woman’s eye - and some subtle revivifying excitement

temporarily dispersed the discontent there - had found her mate long

before he remembered to look in her direction.

The children heard the voices and immediately raced, laughing and

shouting, to meet their fathers. Angela, beating her pinions in a very

frenzy of haste, arrived first. She fluttered away from outstretched

arms until she reached Ralph; he lifted her to his breast, carried her

snuggled there, his lips against her hair. Honey and Pete absently swung

their sons to their shoulders and went on talking. Junior, tired out by

his exertions, sat down plumply half-way. Grinning radiantly, he waited

for the procession to overtake him.

“Peachy,” Julia asked in an aside, “have you ever asked Ralph what he

intends to do about Angela’s wings? “

“What he intends to do?” Peachy echoed. “What do you mean? What can he

intend to do? What has he to say about them, anyway?”

“He may not intend anything,” Julia answered gravely. “Still, if I were

you, I’d have a talk with him.”

Time had brought its changes to the five men as to the five women; but

they were not such devastating changes.

Honey led the march, a huge wreath of uprooted blossoming plants hanging

about his neck. He was at the prime of his strength, the zenith of his

beauty and, in the semi-nudity that the climate permitted, more than

ever like a young wood-god. Health shone from his skin in a

copper-bronze that seemed to overlay the flesh like armor. Happiness

shone from his eyes in a fire-play that seemed never to die down. One

year more and middle age might lay its dulling finger upon him. But now

he positively flared with youth.

Close behind Honey came Billy Fairfax, still shock-headed, his blond

hair faded to tow, slimmer, more serious, more fine. His eyes ran ahead

of the others, found Julia’s face, lighted up. His gaze lingered there

in a tender smile.

Just over Billy’s shoulder, Pete appeared, a Pete as thin and nervous as

ever, the incipient black beard still prickling in tiny ink-spots

through a skin stained a deep mahogany. There was some subtle change in

Pete that was not of the flesh but of the spirit. Perhaps the look in

his face - doubly wild of a Celt and of a genius - had tamed a little.

But in its place had come a question: undoubtedly he had gained in

spiritual dignity and in humorous quality.

Ralph Addington followed Pete. And Ralph also had changed. True, he

retained his inalienable air of elegance, an elegance a little too

sartorial. And even after six years of the jungle, he maintained his

picturesqueness. Long-haired, liquid-eyed, still with a beard

symmetrically pointed and a mustache carefully cropped, he was more than

ever like a young girl’s idea of an artist. And yet something different

had come into his face, The slight touch of gray in his wavy hair did

not account for it; nor the lines, netting delicately his long-lashed

eyes. The eyes themselves bore a baffled expression, half of revolt,

half of resignation; as one who has at last found the immovable

obstacle, who accepts the situation even while he rebels against it.

At the end of the line came Merrill, a doubly transformed man, looking

at the same time younger and handsomer. Bigger and even more muscular

than formerly, his eyes were wide open and sparkling, his mouth had lost

its rigidity of contour. His look of severity, of asceticism had

vanished. Nothing but his classic regularity remained and that had been

beautifully colored by the weather.

The five couples wound through the trail which led from the Playground

to the Camp, the men half-carrying their wives with one arm about their

waists and the other supporting them.

The Camp had changed. The original cabins had spread by an addition of

one or two or three to sprawling bungalow size. Not an atom of their

wooden structure showed. Blocks of green, cubes of color, only open

doorways and windows betrayed that they were dwelling-places. A tide of

tropical jungle beat in waves of green with crests of rainbow up to the

very walls. There it was met by a backwash of the vines which embowered

the cabins, by a stream of blossoms which flooded and cascaded down

their sides.

The married ones stopped at the Camp. But Billy and Julia continued up

the beach.

“How did the work go to-day, Honey?” Lulu asked in a perfunctory tone as

they moved away from the Playground.

“Fine!” Honey answered enthusiastically.

“You wait until you see Recreation Hall.” He stopped to light his pipe.

“Lord, how I wish I had some real tobacco! It’s going to be a corker.

We’ve decided to enlarge the plan by another three feet.”

“Have you really?” commented Lulu. “Dear me, you’ve torn your shirt

again.”

“Yes,” said Honey, puffing violently, “a nail. And we’re going to have a

tennis court at one side not a little squeezed-up affair like this - but

a big, fine one. We’re going to lay out a golf course, too. That will be

some job, Mrs. Holworthy D. Smith, and don’t you forget it.”

“Yes, I should think it would be,” agreed Lulu. “Do you know, Honey,

Clara’s an awful cat! She’s dreadfully jealous of Peachy. The things she

says to her! She knows Pete’s still half in love with her. Peachy

understands him on his art side as Clara can’t. Clara simply hands it to

Pete if he looks at Peachy. Even when she knows that he knows, that we

all know, that she tried her best to start a flirtation with you.”

“And to-day,” Honey interrupted eagerly, “we doped out a scheme for a

series of canals to run right round the whole place - with gardens on

the bank. You see we can pipe the lake water and - - .”

“That will be great,” said Lulu, but there was no enthusiasm in her

tone. “And really, Honey, Peachy’s in a dreadful state of nerves. Of

course, she knows that Ralph is still crazy about Julia and always will

be, just because Julia’s like a stone

Comments (0)