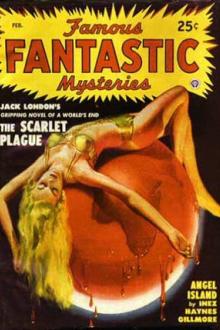

Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗

- Author: Inez Haynes Gillmore

- Performer: -

Book online «Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗». Author Inez Haynes Gillmore

bird. With every breeze, Angela’s wings opened. And always, hands, feet,

hair, feathers fluttered with some temperamental unrest.

The boys tiring of the waves, came scrambling in their direction.

Halfway up the beach, they too came upon the boulder in the path. It

was too high and smooth for them to climb, but they immediately set

themselves to do it. Peterkin pulled himself half-way up, only

immediately to fall back. junior stood for an instant imitatively

reaching up with his baby hands, then abandoning the attempt waddled off

after a big butterfly. Honey-Boy slipped and slid to the ground, but he

was up in an instant and at it again.

Angela fluttered with baby-violence. Julia opened her arms. The child

leaped from her lap, started half-running, half-flying, caught a seaward

going breeze, sailed to the top of the boulder. She balanced herself

there, gazing triumphantly down on Billy-Boy who, flat on his stomach,

red in the face, his black eyes bulging out of his head, still pulled

and tugged and strained.

“Honey-Boy’s tried to climb that rock every day for three months,” Lulu

boasted proudly. “He’ll do it some day. I never saw such persistence. If

he gets a thing into his head, I can’t do anything with him.”

“Angela starts to climb it occasionally,” Peachy said. “But, of course,

I always stop her. I’m afraid she’ll hurt her feet.”

Above the rock stretched the bough of a big pine. As she contemplated

it, a look of wonder grew in Angela’s eyes, of question, of uncertainty.

Suddenly it became resolution. She spread her wings, bounded into the

air, fluttered upwards, and alighted squarely on the bough.

“Oh, Angela!” Peachy called anxiously. Then, joyously, “Look at my baby.

She’ll be flying as high as we did in a few years. Oh, how I love to

think of that!”

She laughed in glee - and the others laughed with her. They continued to

watch Angela’s antics, their faces growing more and more gay. Julia

alone did not smile; but she watched the exhibition none the less

steadily.

Three years had brought some changes to the women of Angel Island; and

for the most part they were devastating changes. They were still

wingless. They wore long trailing garments that concealed their feet.

These garments differed in color and decoration, but they were alike in

one detail-floating, wing-like draperies hung from the shoulders.

Chiquita had grown so large as to be almost unwieldy. But her tropical

coloring retained its vividness, retained its breath-taking quality of

picturesqueness, retained its alluring languor. She sat now holding a

huge fan. Indeed, since the day that Honey had piled the fans on the

beach, Chiquita had never been without one in her hand. Scarlet, the

scarlet of her lost pinions, seemed to be her color. Her gown was

scarlet.

Lulu had not grown big, but she had grown round. That look of the

primitive woman which had made her strange, had softened and sobered.

Her beaute troublante had gone. Her face was, the face of a happy woman.

The maternal look in her eyes was duplicated by the married look in her

figure. She was always busy. Even now, though she chattered, she sewed;

her little fingers fluttered like the wings of an imprisoned bird.

Indeed, she looked like a little sober mother-bird in her gray and brown

draperies. She was the best housewife among them. Honey lacked no

creature comfort.

Clara also had filled out; in figure, she had improved; her elfin

thinness had become slimness, delicately curved and subtly contoured.

Also her coloring had deepened; she was like a woman cast in gold. But

her expression was not pleasant. Her light, gray-green eyes had a

petulant look; her thin, red lips a petulant droop. She was restless;

something about her moved always. Either her long slender fingers

adjusted her hair or her long slender feet beat a tattoo. And ever her

figure shifted from one fluid pose to another. She wore jewels in her

elaborately arranged hair, jewels about her neck, on her wrists, on her

fingers. Her green draperies were embroidered in beads. She was, in

fact, always dressed, costumed is perhaps the most appropriate word. She

dressed Peterkin picturesquely too; she was always, studying the

illustrations in their few books for ideas. Clara was one of those women

at whom instinctively other women gaze - and gaze always with a

question in their eyes.

Peachy was at the height of her blonde bloom; all pearl and gold, all

rose and aquamarine. But something had gone out of her face -

brilliance. And something had come into it - pathos. The look of a

mischievous boy had turned to a wild gipsy look of strangeness, a look

of longing mixed with melancholy. In some respects there was more

history written on her than on any of the others. But it was tragic

history. At Angela’s birth Peachy had gone insane. There had come times

when for hours she shrieked or whispered, “My wings! My wings! My

wings!” The devoted care of the other four women had saved her; she was

absolutely normal now. Her figure still carried its suggestion of a

potential, young-boy-like strength, but maternity had given a droop,

exquisitely feminine, to the shoulders. She always wore blue - something

that floated and shimmered with every move.

Julia had changed little; for in her case, neither marriage nor

maternity had laid its transmogrifying, touch upon her. Her deep

blue-gray eyes - of which the brown-gold lashes seemed like reeds

shadowing lonely lakes - had turned as strange as Peachy’s; but it was a

different strangeness. Her mouth - that double sculpturesque ripple of

which the upper lip protruded an infinitesimal fraction beyond the lower

one - drooped like Clara’s; but it drooped with a different expression.

She had the air of one who looks ever into the distance and broods on

what she sees there. Perhaps because of this, her voice had deepened to

a thrilling intensity. Her hair was pulled straight back to her neck

from the perfect oval of her face. It hung in a single, honey-colored

braid, and it hung to the very ground. She always wore white.

“Do you remember” - Chiquita began presently. Her lazy purring voice

grew soft with tenderness. The dreamy, unthinking Chiquita of four years

back seemed suddenly to peer through the unwieldy Chiquita of the

present - “how we used to fly - and fly - and fly - just for the love of

flying? Do you remember the long, bright day-flyings and the long, dark

night-flyings?

“And sometimes how we used to drop like stones until we almost touched

the water,” Lulu said, a sparkle in her cooing, friendly little voice.

“And the races! Oh, what fun! I can feel the rush of the air now.”

“Over the water.” Peachy flung her long, slim arms upward and a

delicious smile sent the tragedy scurrying from her sunlit face. “Do you

remember how wonderful it was at sunset? The sky heaving over us, shot

with gold and touched with crimson. The sea pulsing under us lined with

crimson and splashed with gold. And then the sunset ahead - that gold

and crimson hole in the sky. We used to think we could fly through it

some day and come out on another world. And sometimes we could not tell

where sea and sky joined. How we flew - on and on - farther each time -

on and on - and on. The risks we took! Sometimes I used to wonder if

we’d ever have the strength to get home. Yet I hated to turn back. I

hated to turn away from the light. I never could fly towards the east at

sunset, nor towards the west at sunrise. It hurt! I used to think, when

my time came to die, that I would fly out to sea - on and on till I

dropped.”

“I loved it most at noon,” Chiquita said, “when the air was soft. It

smelled sweet; a mixture of earth and sea. I used to drift and float on

great seas of heat until I almost slept. That was wonderful; it was like

swimming in a perfumed air or flying in a fragrant sea.”

“Oh, but the storms, Julia!” Lulu exclaimed. A wild look flared in her

face, wiped oft entirely its superficial look of domesticity. “Do you

remember the heavy, night-black cloud, the thunder that crashed through

our very bodies, the lightning that nearly blinded us, and the rain that

beat us almost to pieces?”

“Oh, Lulu!” Julia said; “I had forgotten that. You were wonderful in a

storm, How you used to shout and sing and leap through the air like a

wild thing! I used to love to watch you, and yet I was always afraid

that you would hurt yourself.”

“I loved the moonlight most. I do now.” The petulance went out of

Clara’s eyes; dreams came into its place. “The cool softness of the air,

the brilliant sparkle of the stars! And then the magic of the moonlight!

Young child-moon, half-grown girl-moon, voluptuous woman-moon, sallow,

old-hag-moon, it was alike to me. Pete says I’m ‘fey’ in the moonlight.

He, says I’m Irish then.”

“I loved the sunrise,” said Julia. “I used to steal out, when you girls

were still sleeping, to fly by dawn. I’d go up, up, up. At first, it was

like a huge dewdrop - that morning world - then, colder and colder - it

was like a melted iceberg. But I never minded that cold and I loved the

clearness. It exhilarated me. I used to run races with the birds. I was

not happy until I had beaten the highest-flying of them all. Oh, it was

so fresh and clean then. The world seemed new-made every morning. I used

to feel that I’d caught the moment when yesterday became to-day. Then

I’d sink back through layer on layer of sunlight and warm,

perfume-laden, dew-damp breeze, down, down until I fell into my bed

again. And all the time the world grew warmer and warmer. And I loved

almost as well that instant of twilight when the world begins to fade. I

used to feel that I’d caught the moment when to-day had become

to-morrow. I’d fly as high as I could go then, too. Then I’d sink back

through layer on layer of deepening dusk, while one by one the stars

would flash out at me - down, down, down until my feet touched the

water. And all the time the air grew cooler and cooler.”

“My wings! My wings!” Peachy did not shriek these words with maniacal

despair. She did not whisper them with dreary resignation. She breathed

them with the rapture of one who looks through a narrow, dark tunnel to

measureless reaches of sun-tinted cloud and sea.

“Do you remember the first time we ever saw them?” Lulu asked after a

long time. This was obviously a deliberate harking back to lighter

things. A gleam of reminiscence, both mischievous and tender, fired her

slanting eyes.

The others smiled, too. Even Peachy’s face relaxed from the look of

tension that had come into it. “I often think that was the happiest

time,” she sighed, “those weeks before they knew we were here. At least,

they knew and they didn’t know. Ralph said that they all suspected that

something curious was going on - but that they were so afraid that the

others would joke about it, that no one of them would mention what was

happening to him. Do you remember what fun it was coming to the camp

when they were asleep? Do you remember how we used to study their faces

to find out what

Comments (0)