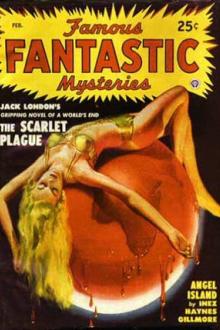

Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗

- Author: Inez Haynes Gillmore

- Performer: -

Book online «Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗». Author Inez Haynes Gillmore

buoyancy, recovered it with a resiliency that had something almost

light-headed about it.

“We won’t touch any of them now,” Frank Merrill ordered peremptorily.

“We can attend to them later. They’ll keep coming back. What we’ve got

to do is to think of the future. Get everything out of the water that

looks useful - immediately useful,” he corrected himself. “Don’t bother

about anything above high-water mark - that’s there to stay. And work

like hell every one of you!”

Work they did for three hours, worked with a kind of frenzied delight in

action and pricked on by a ravenous hunger. In and out of the combers

they dashed, playing a desperate game of chance with Death.

Helter-skelter, hit-or-miss, in a blind orgy of rescue, at first they

pulled out everything they could reach. Repeatedly, Frank Merrill

stopped to lecture them on the foolish risks they were taking, on the

stupidity of such a waste of energy. “Save what we need!’ he iterated

and reiterated, bellowing to make himself heard. “What we can use now -

canned stuff, tools, clothes! This lumber’ll come back on the next

tide.”

He seemed to keep a supervising eye on all of them; for his voice,

shouting individual orders, boomed constantly over the crash of the

waves. Realizing finally that he was the man of the hour, the others

ended by following his instructions blindly.

Merrill, himself, was no shirk. His strength seemed prodigious. When any

of the others attempted to land something too big to handle alone, he

was always near to help; and yet, unaided, he accomplished twice as much

as the busiest.

Frank Merrill, professor of a small university in the Middle West, was

the scholar of the group, a sociologist traveling in the Orient to study

conditions. He was not especially popular with his companions, although

they admired him and deferred to him. On the other hand, he was not

unpopular; it was more that they stood a little in awe of him.

On his mental side, he was a typical academic product. Normally his

conversation, both in subject-matter and in verbal form, bore towards

pedantry. It was one curious effect of this crisis that he had reverted

to the crisp Anglo-Saxon of his farm-nurtured youth.

On his moral side, he was a typical reformer, a man of impeccable

private character, solitary, a little austere. He had never married; he

had never sought the company of women, and in fact he knew nothing about

them. Women had had no more bearing on his life than the fourth

dimension.

On his physical side he was a wonder.

Six feet four in height, two hundred and fifty pounds in weight, he

looked the viking. He had carried to the verge of middle age the habits

of an athletic youth. It was said that half his popularity in his

university world was due to the respect he commanded from the students

because of his extraordinary feats in walking and lifting. He was

impressive, almost handsome. For what of his face his ragged, rusty

beard left uncovered was regularly if coldly featured. He was ascetic in

type. Moreover, the look of the born disciplinarian lay on him. His blue

eyes carried a glacial gleam. Even through his thick mustache, the lines

of his mouth showed iron.

After a while, Honey Smith came across a water-tight tin of matches.

“Great Scott, fellows!” he exclaimed. “I’m hungry enough to drop. Let’s

knock off for a while and feed our faces. How about mock turtle, chicken

livers, and redheaded duck?”

They built a fire, opened cans of soup and vegetables.

“The Waldorf has nothing on that,” Pete Murphy said when they stopped,

gorged.

“Say, remember to look for smokes, all of you,” Ralph Addington

admonished them suddenly.

“You betchu!” groaned Honey Smith, and his look became lugubrious. But

his instinct to turn to the humorous side of things immediately crumpled

his brown face into its attractive smile. “Say, aren’t we going to be

the immaculate little lads? I can’t think of a single bad habit we can

acquire in this place. No smokes, no drinks, few if any eats - and not a

chorister in sight. Let’s organize the Robinson Crusoe Purity League,

Parlor Number One.”

“Oh, gee!” Pete Murphy burst out. “It’s just struck me. The Wilmington

‘Blue,’ is lost forever - it must have gone down with everything else.”

Nobody spoke. It was an interesting indication of how their sense of

values had already shifted that the loss to the world of one of its

biggest diamonds seemed the least of their minor disasters.

“Perhaps that’s what hoodooed us,” Pete went on. “You know they say the

Wilmington ‘Blue’ brought bad luck to everybody who owned it. Anyway,

battle, murder, adultery, rape, rapine, and sudden death have followed

it right along the line down through history. Oh, it’s been a busy cake

of ice - take it from muh! Hope the mermaids fight shy of it.”

“The Wilmington ‘Blue’ isn’t alone in that,” Ralph Addington said. “All

big diamonds have raised hell. You ought to hear some of the stories

they tell in India about the rajahs’ treasures. Some of those briolettes

- you listen long enough and you come to the conclusion that the sooner

all the big stones are cut up, the better.”

“I bet this one isn’t gone,” said Pete. “Anybody take me? That’s the

contrariety of the beasts - they won’t stay lost. We’ll find that stone

yet - where among our loot. The first thing we know, we’ll be all

knifing each other to get it.”

“Time’s up,” called Frank Merrill. “Sorry to drive you, but we’ve got to

keep at it as long as the light lasts. After to-day, though, we need

work only at high water. Between times, we can explore the island - ” He

spoke as if he were wheedling a group of boys with the promise of play.

“Select a site for our capital city” - Honey Smith helped him out

facetiously - “lay out streets - begin to excavate for the church,

town-hall, schoolhouse, and library.”

“The first thing to do now,” Frank Merrill went on, as usual, ignoring

all facetiousness, “is to put up a signal.”

Under his direction, they nailed a pair of sheets, one at the southern,

the other at the northern reef, to saplings which they stripped of

branches. Then they went back to the struggle for salvage.

The fascination of work - and of such novel work - still held them. They

labored the rest of the morning, lay off for a brief lunch, went at it

again in the afternoon, paused for dinner, and worked far into the

evening. Once they stopped long enough to build a huge signal fire on

the each. When they turned in, not one of them but nursed torn and

blistered hands. Not one of them but fell asleep the instant he lay

down.

They slept until long after sunrise.

It was Pete Murphy who waked them. “Say, who was it, yesterday, talked

about seeing black spots? I’m hanged if I’m not hipped, too. When I woke

just before sunrise, there were black things off there in the west. Of

course I was almost dead to the world but - “

“Like great birds?” Billy Fairfax asked with interest.

“Exactly.”

“Bats from your belfry,” commented Ralph Addington. Because of his

constant globe-trotting, Addington’s slang was often a half-decade

behind the times.

“Too much sunlight,” Frank Merrill explained. “Lucky thing, we don’t any

of us have to wear glasses. We’d certainly be up against it in this

double glare. Sand and sun both, you see! And you can thank whatever

instinct that’s kept you all in training. This shipwreck is the most

perfect case I’ve ever seen of the survival of the fittest.”

And in fact, they were all, except for Pete Murphy, big men, and all,

even he, active, strong-muscled, and in the pink of condition.

The huge tide had not entirely subsided, but there was a perceptible

diminution in the height of the waves. Up beyond the water-line lay a

fresh installment of jetsam. But, as before, they labored only to save

the flotsam. They worked all the morning.

In the afternoon, they dug a huge trench. Frank Merrill presiding, they

buried the dead with appropriate ceremony.

“Thank God, that’s done,” Ralph Addington said with a shudder. “I hate

death and everything to do with it.”

“Yes, we’ll all be more normal now they’re gone,” Frank Merrill added.

“And the sooner everything that reminds us of them is gone the better.”

“Say,” Honey Smith burst out the next morning. “Funny thing happened to

me in the middle the night. I woke out of a sound sleep - don’t know why

- woke with a start as if somebody’d shaken me - felt something brush me

so close - well, it touched me. I was so dead that I had to work like

the merry Hades to open my eyes - seemed as if it was a full minute

before I could lift my eyelids. When I could make things out - damned if

there wasn’t a bird - a big bird - the biggest bird I ever saw in my

life - three times as big as any eagle - flying over the water.”

Nothing could better have indicated Honey’s mental turmoil than the fact

that he talked in broken phrases rather than in his usual clear,

swift-footed curt sentences.

Nobody noticed this. Nobody offered comment. Nobody seemed surprised. In

fact, all the psychological areas which explode in surprise and wonder

were temporarily deadened.

“As sure as I live,” Honey continued indignantly, “that bird’s wings

must have extended twenty feet above its head.”

“Oh, get out!” said Ralph Addington perfunctorily.

“As sure as I’m sitting here,” Honey went on earnestly. “I heard a

woman’s laugh. Any of you others get it?”

The sense of humor, it seemed, was not extinct. Honey’s companions burst

into roars of laughter. For the rest of the morning, they joked Honey

about his hallucination. And Honey, who always responded in kind to any

badinage, received this in silence. In fact, wherever he could, a little

pointedly, he changed the subject.

Honey Smith was the type of man whom everybody jokes, partly because he

received it with such good humor, partly because he turned it back with

so ready and so charming a wit. Also it gave his fellow creatures a

gratifying sense of equality to pick humorous flaws in one so manifestly

a darling of the gods.

Honey Smith possessed not a trace of genius, not a suggestion of what is

popularly termed “temperament.” He had no mind to speak of, and not more

than the usual amount of character. In fact, but for one thing, he was

an average person. That one thing was personality - and personality he

possessed to an extraordinary degree. Indeed, there seemed to be

something mysteriously compelling about this personality of Honey’s. The

whole world of creatures felt its charm. Dumb beasts fawned on him.

Children clung to him. Old people lingered near as though they could

light dead fires in the blaze of his radiant youth. Men hobnobbed with

him; his charm brushed off on to the dryest and dullest so that,

temporarily, they too bloomed with personality. As for women - His

appearance among them was the signal for a noiseless social cataclysm.

They slipped and slid in his direction as helplessly as if an inclined

plane had opened under their feet. They fluttered in circles about him

like birds around a light. If he had been

Comments (0)