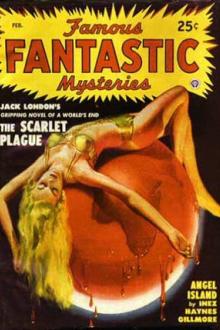

Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗

- Author: Inez Haynes Gillmore

- Performer: -

Book online «Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗». Author Inez Haynes Gillmore

his inclination, they would have held a subsidiary place in his

existence. For he was practical, balanced, sane. He had, moreover, the

tendency towards temperance of the born athlete. Besides all this, his

main interests were man-interests. But women would not let him alone. He

had but to look and the thing was done. Wreaths hung on every balcony

for Honey Smith and, always at his approach, the door of the harem swung

wide. He was a little lazy, almost discourteously uninterested in his

attitude towards, the individual female; for he had never had to exert

himself.

It is likely that all this personal popularity would have been the

result of that trick of personality. But many good fairies had been

summoned to Honey’s christening; he had good looks besides. He was

really tall, although his broad shoulders seemed to reduce him to medium

height. Brown-skinned, brown-eyed, brown-haired, his skin was as smooth

as satin, his eyes as clear as crystal, his hair as thick as fur. His

expression had tremendous sparkle. But his main physical charm was a

smile which crumpled his brown face into an engaging irregularity of

contour and lighted it with an expression brilliant with mirth and

friendliness.

He was a true soldier of fortune. In the ten years which his business

career covered be had engaged in a score of business ventures. He had

lost two fortunes. Born in the West, educated in the East, he had

flashed from coast to coast so often that he himself would have found it

hard to say where he belonged.

He was the admiration and the wonder and the paragon and the criterion

of his friend Billy Fairfax, who had trailed his meteoric course through

college and who, when the Brian Boru went down, was accompanying him on

his most recent adventure - a globe-trotting trip in the interests of a

moving-picture company. Socially they made an excellent team. For Billy

contributed money, birth, breeding, and position to augment Honey’s

initiative, enterprise, audacity, and charm. Billy Fairfax offered other

contrasts quite as striking. On his physical side, he was shapelessly

strong and hopelessly ugly, a big, shock-headed blond. On his personal

side “mere mutt-man” was the way one girl put it, “too much of a damned

gentleman” Honey Smith said to him regularly.

Billy Fairfax was not, however, without charm of a certain shy, evasive,

slow-going kind; and he was not without his own distinction. His huge

fortune had permitted him to cultivate many expensive sports and

sporting tastes. His studs and kennels and strings of polo ponies were

famous. He was a polo-player well above the average and an aviator not

far below it.

Pete Murphy, the fifth of the group, was the delight of them all. The

carriage of a bantam rooster, the courage of a lion, more brain than he

could stagger under; a disposition fiery, mercurial, sanguine, witty; he

was made, according to Billy Fairfax’s dictum, of “wire and brass

tacks,” and he possessed what Honey Smith (who himself had no mean gift

in that direction) called “the gift of gab.” He lived by writing

magazine articles. Also he wrote fiction, verse, and drama. Also he was

a painter. Also he was a musician. In short, he was an Irishman.

Artistically, he had all the perception of the Celt plus the acquired

sapience of the painter’s training. If he could have existed in a

universe which consisted entirely of sound and color, a universe

inhabited only by disembodied spirits, he would have been its ablest

citizen; but he was utterly disqualified to live in a human world. He

was absolutely incapable of judging people. His tendency was to

underestimate men and to overestimate women. His life bore all the scars

inevitable to such an instinct. Women, in particular, had played ducks

and drakes with his career. Weakly chivalrous, mindlessly gallant, he

lacked the faculty of learning by experience - especially where the

other sex were concerned. “Predestined to be stung!” was, his first

wife’s laconic comment on her ex-husband. She, for instance, was

undoubtedly the blameworthy one in their marital failure, but she had

managed to extract a ruinous alimony from him. Twice married and twice

divorced, he was traveled through the Orient to write a series of muck

raking articles and, incidentally if possible, to forget his last

unhappy matrimonial venture.

Physically, Pete was the black type of Celt. The wild thatch of his

scrubbing-brush hair shone purple in the light. Scrape his face as he

would, the purple shadow of his beard seemed ingrained in his white

white skin. Black-browed and black-lashed, he had the luminous

blue-gray-green eyes of the colleen. There was a curious untamable

quality in his look that was the mixture of two mad strains, the

aloofness of the Celt and the aloofness of the genius.

Three weeks passed. The clear, warm-cool, lucid, sunny weather kept up.

The ocean flattened, gradually. Twice every twenty-four hours the tide

brought treasure; but it brought less and less every day. Occasionally

came a stiffened human reminder of their great disaster. But calloused

as they were now to these experiences, the men buried it with hasty

ceremony and forgot.

By this time an incongruous collection stretched in parallel lines above

the high-water mark. “Something, anything, everything - and then some,”

remarked Honey Smith. Wood wreckage of all descriptions, acres of

furniture, broken, split, blistered, discolored, swollen; piles of

carpets, rugs, towels, bed-linen, stained, faded, shrunken, torn; files

of swollen mattresses, pillows, cushions, life-preservers; heaps of

table-silver and kitchen-ware tarnished and rusty; mounds of china and

glass; mountains of tinned goods, barrels boxes, books, suit-cases,

leather bags; trunks and trunks and more trunks and still more trunks;

for, mainly, the trunks had saved themselves.

Part of the time, in between tides, they tried to separate the grain of

this huge collection of lumber from the chaff; part of the time they

made exploring trips into the interior. At night they sat about their

huge fire and talked.

The island proved to be about twenty miles in length by seven in width.

It was uninhabited and there were no large animals on it. It was Frank

Merrill’s theory that it was the exposed peak of a huge extinct volcano.

In the center, filling the crater, was a little fresh-water lake. The

island was heavily wooded; but in contour it presented only diminutive

contrasts of hill and valley. And except as the semi-tropical foliage

offered novelties of leaf and flower, the beauties of unfamiliar shapes

and colors, it did not seem particularly interesting. Ralph Addington

was the guide of these expeditions. From this tree, he pointed out, the

South Sea Islander manufactured the tappa cloth, from that the

poeepooee, from yonder the arva. Honey Smith used to say that the only

depressing thing about these trips was the utter silence of the gorgeous

birds which they saw on every side. On the other hand, they extracted

what comfort they could from Merrill’s and Addington’s assurance that,

should the ship’s supply give out, they could live comfortably enough on

birds’ eggs, fruit, and fish.

Sorting what Honey Smith called the “ship-duffle” was one prolonged

adventure. At first they made little progress; for all five of them

gathered over each important find, chattering like girls. Each man

followed the bent of his individual instinct for acquisitiveness. Frank

Merrill picked out books, paper, writing materials of every sort. Ralph

Addington ran to clothes. The habit of the man with whom it is a

business policy to appear well-dressed maintained itself; even in their

Eveless Eden, he presented a certain tailored smartness. Billy Fairfax

selected kitchen utensils and tools. Later, he came across a box filled

with tennis rackets, nets, and balls. The rackets’ strings had snapped

and the balls were dead. He began immediately to restring the rackets,

to make new balls from twine, to lay out a court. Like true soldiers of

fortune, Honey Smith and Pete Murphy made no special collection; they

looted for mere loot’s sake.

One day, in the midst of one of their raids, Honey Smith yelled a

surprised and triumphant, “By jiminy!” The others showed no signs, of

interest. Honey was an alarmist; the treasure of the moment might prove

to be a Japanese print or a corkscrew. But as nobody stirred or spoke,

he called, “The Wilmington ‘Blue’!”

These words carried their inevitable magic. His companions dropped

everything; they swarmed about him.

Honey held on his palm what, in the brilliant sunlight looked like a

globe of blue fire, a fire that emitted rainbows instead of sparks.

He passed it from hand to hand. It seemed a miracle that the fingers

which touched it did not burst into flame. For a moment the five men

might have been five children.

“Well,” said Pete Murphy, “according to all fiction precedent, the rest

of us ought to get together immediately, if not a little sooner, and

murder you, Honey.”

“Go as far as you like,” said Honey, dropping the stone into the pocket

of his flannel shirt. “Only if anybody really gets peeved about this

junk of carbon, I’ll give it to him.”

For a while life flowed wonderful. The men labored with a joy-in-work at

which they themselves marveled. Their out-of-doors existence showed its

effects in a condition of glowing health. Honey Smith changed first to a

brilliant red, then to a uniform coffee brown, and last to a shining

bronze which was the mixture of both these colors. Pete Murphy grew one

crop of freckles, then another and still another until Honey offered to

“excavate” his features. Ralph Addington developed a rich, subcutaneous,

golden-umber glow which made him seem, in connection with an occasional

unconventionality of costume, more than ever like the schoolgirl’s idea

of an artist. Billy Fairfax’s blond hair bleached to flaxen. His

complexion deepened in tone to a permanent pink. This, in contrast with

the deep clear blue of his eyes, gave him a kind of out-of-doors

comeliness. But Frank Merrill was the surprise of them all. He not only

grew handsomer, he grew younger; a magnificent, towering, copper-colored

monolith of a man, whose gray eyes were as clear as mountain springs,

whose white teeth turned his smile to a flash of light. Constantly they

patrolled the beach, pairs of them, studying the ocean for sight of a

distant sail, selecting at intervals a new spot on which at night to

start fires, or by day to erect signals. They bubbled with spirits. They

laughed and talked without cessation. The condition which Ralph

Addington had deplored, the absence of women, made first for social

relaxation, for psychological rest.

“Lord, I never noticed before - until I got this chance to get off and

think of it - what a damned bother women are,” Honey Smith said one day.

“Of all the sexes that roam the earth, as George Ade says, I like them

least. What a mess they make of your time and your work, always

requiring so much attention, always having to be waited on, always

dropping things, always so much foolish fuss and ceremony, always asking

such footless questions and never hearing you when you answer them.

Never really knowing anything or saying anything. They’re a different

kind of critter, that’s all there is to it; they’re amateurs at life.

They’re a failure as a sex and an outworn convention anyway. Myself, I’m

for sending them to the scrap-heap. Votes for men!”

And with this, according to the divagations of their temperaments and

characters, the others strenuously concurred.

Their days, crowded to the brim with work, passed so swiftly that they

scarcely noticed their flight. Their nights, filled with a sleep that

was twin brother to Death, seemed not to exist at all.

Their evenings were lively with

Comments (0)