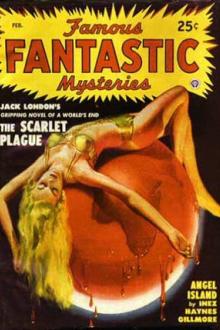

Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗

- Author: Inez Haynes Gillmore

- Performer: -

Book online «Angel Island - Inez Haynes Gillmore (novels to improve english .TXT) 📗». Author Inez Haynes Gillmore

a strangely subdued quintette. It was as though they were all trying to

comment on these experiences without saying anything about them.

They slept through the next night undisturbed until just before sunrise.

Then Honey Smith woke them. It was still dark, but a fine dawn-glow had

begun faintly to silver the east. “Say, you fellows,” he exclaimed.

“Wake up!” His voice vibrated with excitement, although he seemed to try

to keep it low. “There are strange critters round here. No mistake this

time. Woke with a start, feeling that something had brushed over me -

saw a great bird - a gigantic thing - flying off heard one woman’s laugh

- then another - .”

It was significant that nobody joked Honey this time. “Say, this

island’ll be a nut-house if this keeps up,” Pete Murphy said irritably.

“Let’s go to sleep again.”

“No, you don’t!” said Honey. “Not one of you is going to sleep. You’re

all going to sit up with me until the blasted sun comes up.”

People always hastened to accommodate Honey. In spite of the hour, they

began to rake the fire, to prepare breakfast. The others became

preoccupied gradually, but Honey still sat with his face towards the

water, watching.

It grew brighter.

“It’s time we started to build a camp, boys,” Frank Merrill said,

withdrawing momentarily from deep reflection. “We’ll go crazy doing

nothing all the time. We’ll - .”

“Great God,” Honey interrupted. “Look!”

Far out to sea and high in the air, birds were flying. There were five

of them and they were enormous. They flew with amazing strength,

swiftness, and grace; but for the most part they about a fixed area like

bees at a honey-pot. It was a limited area, but within it they dipped,

dropped, curved, wove in and out.

“Well, I’ll be - .”

“They’re those black spots we saw the first day, Pete,” Billy Fairfax

said breathlessly. “We thought it was the sun.”

“That’s what I heard in the night,” Frank Merrill gasped to Ralph

Addington.

“But what are they?” asked Honey Smith in a voice that had a falsetto

note of wonder. “They laugh like a woman - take it from me.”

“Eagles - buzzards - vultures - condors - rocs - phoenixes,” Pete Murphy

recited his list in an or of imaginative conjecture.

“They’re some lost species - something left over from a prehistoric era,”

Frank Merrill explained, shaking with excitement. “No vulture or eagle

or condor could be as big as that at this distance. At least I think

so.” He paused here, as one studying the problem in the scientific

spirit. “Often in the Rockies I’ve confused a nearby chicken-hawk, at

first, with a far eagle. But the human eye has its own system of

triangulation. Those are not little birds nearby, but big birds far off.

See how heavily they soar. Do you realize what’s happened? We’ve made a

discovery that will shake the whole scientific world. There, there,

they’re going!”

“My God, look at them beat it!” said Honey; and there was awe in his

voice.

“Why, they’re monster size,” Frank Merrill went on, and his voice had

grown almost hysterical. “They could carry one of us off. We’re not

safe. We must take measures at once to protect ourselves. Why, at night

- We must make traps. If we can capture one, or, better, a pair, we’re

famous. We’re a part of history now.”

They watched the strange birds disappear over the water. For more than

an hour, the men sat still, waiting for them to return. They did not

come back, however. The men hung about camp all day long, talking of

nothing else. Night came at last, but sleep was not in them. The dark

seemed to give a fresh impulse to conversation. Conjecture battled with

theory and fact jousted with fancy. But one conclusion was as futile as

another.

Frank Merrill tried to make them devise some system of defense or

concealment, but the others laughed at him. Talk as he would, he could

not seem to convince them of their danger. Indeed, their state of mind

was entirely different from his. Mentally he seemed to boil with

interest and curiosity, but it was the sane, calm, open-minded

excitement of the scientist. The others were alert and preoccupied in

turn, but there was an element of reserve in their attitude. Their eyes

kept going off into space, fixing there until their look became one

brooding question. They avoided conversation. They avoided each other’s

gaze.

Gradually they drew off from the fire, settled themselves to rest, fell

into the splendid sleep that followed their long out-of-doors days.

In the middle of the night, Billy Fairfax came out of a dream to the

knowledge that somebody was shaking him gently, firmly, furtively.

“Don’t move!” Honey Smith’s voice whispered; “keep quiet till I wake the

others.”

It was a still and moonlighted world. Billy Fairfax lay quiet, his

wide-open eyes fixed on the luminous sky. The sense of drowse was being

brushed out of his brain as though by a mighty whirlwind, and in its

place came a vague sensation of confusion, of excitement, of a

miraculous abnormality. He heard Honey Smith crawl slowly from man to

man, heard him whisper his adjuration once, twice, three times. “Now,”

Honey called finally.

The men looked seawards. Then, simultaneously they leaped to their feet.

The semi-tropical moon was at its full. Huge, white, embossed, cut out,

it did not shine - it glared from the sky. It made a melted moonstone of

the atmosphere. It faded the few clouds to a sapphire-gray, just touched

here and there with the chalky dot of a star. It slashed a silver trail

across a sea jet-black except where the waves rimmed it with snow. Up in

the white enchantment, but not far above them, the strange air-creatures

were flying. They were not birds; they were winged women!

Darting, diving, glancing, curving, wheeling, they interwove in what

seemed the premeditated figures of an aerial dance. If they were

conscious of the group of men on the beach, they did not show it; they

seemed entirely absorbed in their flying. Their wings, like enormous

scimitars, caught the moonlight, flashed it back. For an interval, they

played close in a group inextricably intertwined, a revolving ball of

vivid color. Then, as if seized by a common impulse, they stretched,

hand in hand, in a line across the sky-drifted. The moonlight flooded

them full, caught glitter and gleam from wing-sockets, shot shimmer and

sheen from wing-tips, sent cataracts of iridescent color pulsing

between. Snow-silver one, brilliant green and gold another, dazzling

blue the next, luminous orange a fourth, flaming flamingo scarlet the

last, their colors seemed half liquid, half light. One moment the whole

figure would flare into a splendid blaze, as if an inner mechanism had

suddenly turned on all the electricity; the next, the blaze died down to

the fairy glisten given by the moonlight.

As if by one impulse, they began finally to fly upward. Higher and

higher they rose, still hand in hand. Detail of color and movement

vanished. The connotation of the sexed creature, of the human thing,

evaporated. One instant, relaxed, they seemed tiny galleons, all sails

set, that floated lazily, the sport of an aerial sea; another, supple

and sinuous, they seemed monstrous fish whose fins triumphantly clove

the air, monarchs of that aerial sea.

A little of this and then came another impulse. The great wings furled

close like blades leaping back to scabbard; the flying-girls dropped

sheer in a dizzying fall. Halfway to the ground, they stopped

simultaneously as if caught by some invisible air plateau. The great

feathery fans opened - and this time the men got the whipping whirr of

them - spread high, palpitated with color. From this lower level, the

girls began to fall again, but gently, like dropping clouds.

Nearer they came to the petrified group on the beach, nearer and nearer.

Undoubtedly they had known all the time that an audience was there;

undoubtedly they had planned this; they looked down and smiled.

And now the men had every detail of them - the brown seaweeds and green

sea-grasses that swathed them, their bodies just short of heroic size,

deep-bosomed, broad-waisted, long-limbed; their arms round like a

woman’s and strong like a man’s; their hair that fell, a braid over each

ear, twined with brilliant flowers and green vines; their faces

superhumanly beautiful, though elvish; the gaminerie in their laughing

eyes, which sparkled through half-closed, thick-lashed lids, the

gaminerie in their smiling mouths, which showed twin rows of pearl

gleaming in tricksy mirth; their big, strong-looking, long-fingered

hands; their slimly smooth, exquisitely shaped, too-tiny, transparent

feet; their strong wrists; their stem-like, breakable ankles. Closer and

closer and closer they came. And now the men could almost touch them.

They paused an instant and fluttered - fluttered like a swarm of

butterflies undecided where to fly. As though choosing to rest, they

hovered-hovered with a gentle, slow, seductive undulation of wings, of

hands, of feet.

Then another impulse took them.

They broke handclasps and up they went, like arrows straight up - up -

up - up. Then they turned out to sea, streaming through the air in line

still, but one behind the other. And for the first time, sound came from

them; they threw off peals of girl-laughter that fell like handfuls of

diamonds. Their mirth ended in a long, eerie cry. Then straight out to

the eastern horizon they went and away and off.

They were dwindling rapidly.

They were spots.

They were specks.

They were nothing.

IISilence, profound, portentous, protracted, followed.

Finally, Honey Smith absently stooped and picked up a pebble. He threw

it over the silver ring of the flat, foam-edged, low-tide waves. It

curved downwards, hissed across a surface of water smooth as jade,

skipped four times, and dropped.

The men strained their eyes to follow the progress of this tangible

thing.

“Where do you suppose they’ve gone?” Honey said as unexcitedly as one

might inquire directions from a stranger.

“When do you suppose they’ll come back?” Billy Fairfax added as casually

as one might ask the time.

“Did you notice the redheaded one?” asked Pete Murphy. “My first girl

had red hair. I always jump when I see a carrot-top.” He made this

intimate revelation simply, as if the time for a conventional reticence

had passed.

“They were lookers all right,” Ralph Addington went on. “I’d pick the

golden blonde, the second from the right.” He, too, spoke in a

matter-of-fact tone, as though he were selecting a favorite from the

front row in the chorus.

“It must have happened if we saw it,” Frank Merrill said. There was in

his voice a note of petulance, almost childish. “But we ought not to

have seen it. It has no right to be. It upsets things so.”

“What are we all standing up like gawks for?” Pete Murphy demanded with

a sudden irritability.

“Sit down!”

Everybody dropped. They all sat as they fell. They sat motionless. They

sat silent.

“The name of this place is ‘Angel Island,’” announced Billy Fairfax

after a long time. His tone was that of a man whose thoughts, swirling

in phantasmagoria, seek anchorage in fact.

They did not sleep that night.

When Frank Merrill arose the next morning, Ralph Addington was just

returning from a stroll down the beach. Ralph looked at the same time

exhausted and recuperated. He was white, tense, wild-eyed, but recently

aroused interior fires glowed through his skin,

Comments (0)