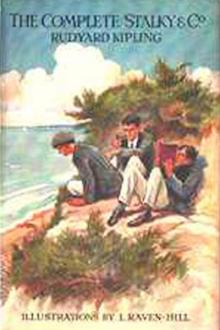

Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗

- Author: Rudyard Kipling

- Performer: -

Book online «Stalky & Co. - Rudyard Kipling (ebooks children's books free TXT) 📗». Author Rudyard Kipling

“An’ it’s all goin’ up to the ‘Ead. Oh, Good Lord!”

“Every giddy word of it, my Chingangook,” said Beetle, dancing. “Why shouldn’t it? We’ve done nothing wrong. We ain’t poachers. We didn’t cut about blastin’ the characters of poor, innocent boys—saying they were drunk.”

“That I didn’t,” said Foxy. “I—I only said that you be’aved uncommon odd when you come back with that badger. Mr. King may have taken the wrong hint from that.”

“‘Course he did; an’ he’ll jolly well shove all the blame on you when he finds out he’s wrong. We know King, if you don’t. I’m ashamed of you. You ain’t fit to be a sergeant,” said McTurk.

“Not with three thorough-goin’ young devils like you, I ain’t. I’ve been had. I’ve been ambuscaded. Horse, foot, an’ guns, I’ve been had, an’—an’ there’ll be no holdin’ the junior forms after this. M’rover, the ‘Ead will send me with a note to Colonel Dabney to ask if what you say about bein’ invited was true.”

“Then you’d better go in by the Lodge-gates this time, instead of chasin’ your dam’ boys—oh, that was the Epistle to King—so it was. We-el, Foxy?” Stalky put his chin on his hands and regarded the victim with deep delight.

“Ti-ra-la-la-i-tu! I gloat! Hear me!” said McTurk. “Foxy brought us tea when we were moral lepers. Foxy has a heart. Foxy has been in the Army, too.”

“I wish I’d ha’ had you in my company, young gentlemen,” said the Sergeant from the depths of his heart; “I’d ha’ given you something.”

“Silence at drumhead court-martial,” McTurk went on. “I’m advocate for the prisoner; and, besides, this is much too good to tell all the other brutes in the Coll. They’d never understand. They play cricket, and say: ‘Yes sir,’ and ‘O, sir,’ and ‘No, sir.’”

“Never mind that. Go ahead,” said Stalky.

“Well, Foxy’s a good little chap when he does not esteem himself so as to be clever.”

“‘Take not out your ‘ounds on a werry windy day,’” Stalky struck in. “I don’t care if you let him off.”

“Nor me,” said Beetle. “Heffy is my only joy—Heffy and King.”

“I ‘ad to do it,” said the Sergeant, plaintively.

“Right, O! Led away by bad companions in the execution of his duty or—or words to that effect. You’re dismissed with a reprimand, Foxy. We won’t tell about you. I swear we won’t,” McTurk concluded. “Bad for the discipline of the school. Horrid bad.”

“Well,” said the Sergeant, gathering up the tea-things, “knowin’ what I know o’ the young dev—gentlemen of the College, I’m very glad to ‘ear it. But what am I to tell the ‘Ead?”

“Anything you jolly well please, Foxy. We aren’t the criminals.”

To say that the Head was annoyed when the Sergeant appeared after dinner with the day’s crime-sheet would be putting it mildly.

“Corkran, McTurk, and Co., I see. Bounds as usual. Hullo! What the deuce is this? Suspicion of drinking. Whose charge??”

“Mr. King’s, sir. I caught ‘em out of bounds, sir: at least that was ‘ow it looked. But there’s a lot be’ind, sir.” The Sergeant was evidently troubled.

“Go on,” said the Head. “Let us have your version.” He and the Sergeant had dealt with one another for some seven years; and the Head knew that Mr. King’s statements depended very largely on Mr. King’s temper.

“I thought they were out of bounds along the cliffs. But it come out they wasn’t, sir. I saw them go into Colonel Dabney’s woods, and—Mr. King and Mr. Prout come along—and the fact was, sir, we was mistook for poachers by Colonel Dabney’s people—Mr. King and Mr. Prout and me. There were some words, sir, on both sides. The young gentlemen slipped ‘ome somehow, and they seemed ‘ighly humorous, sir. Mr. King was mistook by Colonel Dabney himself—Colonel Dabney bein’ strict. Then they preferred to come straight to you, sir, on account of what—what Mr. King may ‘ave said about their ‘abits afterwards in Mr. Prout’s study. I only said they was ‘ighly humorous, laughin’ an’ gigglin’, an’ a bit above ‘emselves. They’ve since told me, sir, in a humorous way, that they was invited by Colonel Dabney to go into ‘is woods.”

“I see. They didn’t tell their housemaster that, of course?”

“They took up Mr. King on appeal just as soon as he spoke about their—‘abits. Put in the appeal at once, sir, an’ asked to be sent to the dormitory waitin’ for you. I’ve since gathered, sir, in their humorous way, sir, that some’ow or other they’ve ‘eard about every word Colonel Dabney said to Mr. King and Mr. Prout when he mistook ‘em for poachers. I—I might ha’ known when they led me on so that they ‘eld the inner line of communications. It’s—it’s a plain do, sir, if you ask me; an’ they’re gloatin’ over it in the dormitory.”

The Head saw—saw even to the uttermost farthing—and his mouth twitched a little under his mustache.

“Send them to me at once, Sergeant. This case needn’t wait over.”

“Good evening,” said he when the three appeared under escort. “I want your undivided attention for a few minutes. You’ve known me for five years, and I’ve known you for—twenty-five. I think we understand one another perfectly. I am now going to pay you a tremendous compliment (the brown one, please, Sergeant. Thanks. You needn’t wait). I’m going to execute you without rhyme, Beetle, or reason. I know you went to Colonel Dabney’s covers because you were invited. I’m not even going to send the Sergeant with a note to ask if your statement is true; because I am convinced that on this occasion you have adhered strictly to the truth. I know, too, that you were not drinking. (You can take off that virtuous expression, McTurk, or I shall begin to fear you don’t understand me.) There is not a flaw in any of your characters. And that is why I am going to perpetrate a howling injustice. Your reputations have been injured, haven’t they? You have been disgraced before the house, haven’t you? You have a peculiarly keen regard for the honor of your house, haven’t you? Well, now I am going to lick you.”

Six apiece was their portion upon that word.

“And this I think”—the Head replaced the cane, and flung the written charge into the waste-paper basket—“covers the situation. When you find a variation from the normal—this will be useful to you in later life—always meet him in an abnormal way. And that reminds me. There are a pile of paper-backs on that shelf. You can borrow them if you put them back. I don’t think they’ll take any harm from being read in the open. They smell of tobacco rather. You will go to prep. this evening as usual. Good-night,” said that amazing man.

“Good-night, and thank you, sir.”

“I swear I’ll pray for the Head to-night,” said Beetle. “Those last two cuts were just flicks on my collar. There’s a ‘Monte Cristo’ in that lower shelf. I saw it. Bags I, next time we go to Aves!”

“Dearr man!” said McTurk. “No gating. No impots. No beastly questions. All settled. Hullo! what’s King goin’ in to him for—King and Prout?”

Whatever the nature of that interview, it did not improve either King’s or Prout’s ruffled plumes, for, when they came out of the Head’s house, eyes noted that the one was red and blue with emotion as to his nose, and that the other was sweating profusely. That sight compensated them amply for the Imperial Jaw with which they were favored by the two. It seems—and who so astonished as they?—that they had held back material facts; were guilty both of suppressioveri_ and suggestiofalsi_ (well-known gods against whom they often offended); further, that they were malignant in their dispositions, untrustworthy in their characters, pernicious and revolutionary in their influences, abandoned to the devils of wilfulness, pride, and a most intolerable conceit. Ninthly, and lastly, they were to have a care and to be very careful.

They were careful, as only boys can be when there is a hurt to be inflicted. They waited through one suffocating week till Prout and King were their royal selves again; waited till there was a house-match—their own house, too—in which Prout was taking part; waited, further, till he had his pads in the pavilion and stood ready to go forth. King was scoring at the window, and the three sat on a bench without.

Said Stalky to Beetle: “I say, Beetle,_quis_custodet_ipsos_custodes_?”

“Don’t ask me,” said Beetle. “I’ll have nothin’ private with you. Ye can be as private as ye please the other end of the bench; and I wish ye a very good afternoon.”

McTurk yawned.

“Well, ye should ha’ come up to the lodge like Christians instead o’ chasin’ your—a-hem—boys through the length an’ breadth of my covers. I think these house-matches are all rot. Let’s go over to Colonel Dabney’s an’ see if he’s collared any more poachers.”

That afternoon there was joy in Aves.

SLAVES OF THE LAMP

The music-room on the top floor of Number Five was filled with the “Aladdin” company at rehearsal. Dickson Quartus, commonly known as Dick Four, was Aladdin, stage-manager, ballet-master, half the orchestra, and largely librettist, for the “book” had been rewritten and filled with local allusions. The pantomime was to be given next week, in the down-stairs study occupied by Aladdin, Abanazar, and the Emperor of China. The Slave of the Lamp, with the Princess Badroulbadour and the Widow Twankay, owned Number Five study across the same landing, so that the company could be easily assembled. The floor shook to the stamp-and-go of the ballet, while Aladdin, in pink cotton tights, a blue and tinsel jacket, and a plumed hat, banged alternately on the piano and his banjo. He was the moving spirit of the game, as befitted a senior who had passed his Army Preliminary and hoped to enter Sandhurst next spring.

Aladdin came to his own at last, Abanazar lay poisoned on the floor, the Widow Twankay danced her dance, and the company decided it would “come all right on the night.”

“What about the last song, though?” said the Emperor, a tallish, fair-headed boy with a ghost of a mustache, at which he pulled manfully. “We need a rousing old tune.”

“‘John Peel’? ‘Drink, Puppy, Drink’?” suggested Abanazar, smoothing his baggy lilac pajamas. “Pussy” Abanazar never looked more than one-half awake, but he owned a soft, slow smile which well suited the part of the Wicked Uncle.

“Stale,” said Aladdin. “Might as well have ‘Grandfather’s Clock.’ What’s that thing you were humming at prep. last night, Stalky?”

Stalky, The Slave of the Lamp, in black tights and doublet, a black silk half-mask on his forehead, whistled lazily where he lay on the top of the piano. It was a catchy music-hall tune.

Dick Four cocked his head critically, and squinted down a large red nose.

“Once more, and I can pick it up,” he said, strumming. “Sing the words.”

“Arrah, Patsy, mind the baby! Arrah, Patsy, mind the child! Wrap him in an overcoat, he’s surely going wild! Arrah, Patsy, mind the baby! just you mind the child awhile! He’ll kick and bite and cry all night! Arrah, Patsy, mind the child!”

“Rippin’! Oh, rippin’!” said Dick Four. “Only we shan’t have any piano on the night. We must work it with the banjoes—play an’ dance at the same time. You try, Tertius.”

The Emperor pushed aside his pea-green sleeves of state, and followed Dick Four on a heavy nickel plated banjo.

“Yes, but I’m dead all this time. Bung in the middle of

Comments (0)